Mitt Romney Is Trying to Save Policymaking

In 2021, it’s news when a legislator suggests a policy reform for any reason other than naked ambition.

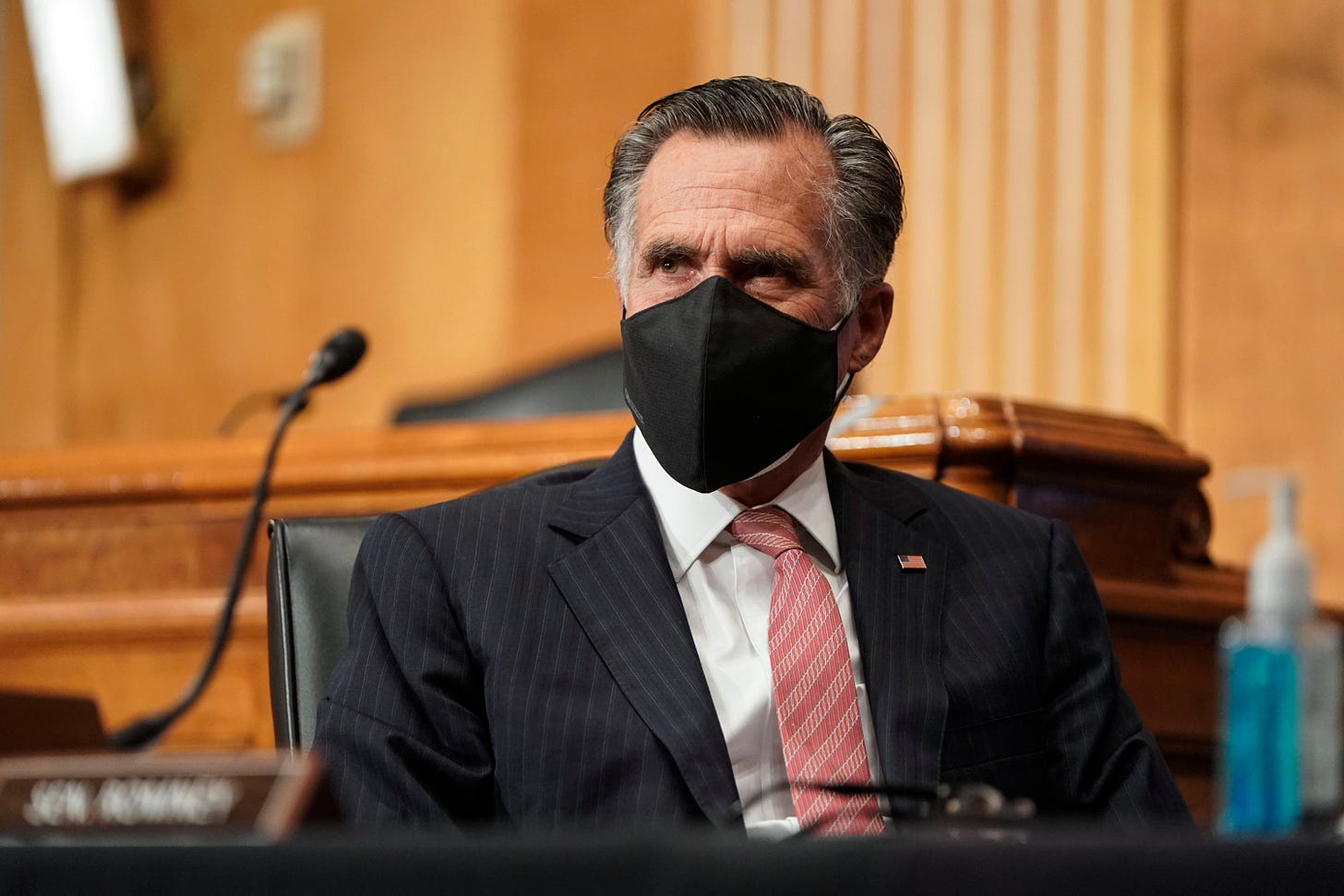

It may be coincidence that the best policy idea to come out of the 117th Congress was offered by the one guy who has demonstrated the integrity to brave harassment and death threats to do what’s right vis-à-vis Trump. Or maybe not, because Sen. Mitt Romney is among a nearly extinct species in the Republican party—an elected official who is interested in something other than his own ambition. And when you’re actually interested in public policy, you suggest reforms.

This country has a serious child problem. Our birth rates are low and heading lower, which endangers the prospects for Social Security and Medicare for our large elderly population. Also, old countries tend to lack dynamism, which has always been an American specialty. Some couples are happy with their small family sizes, but most Americans want more children (2.7) than they are likely to have (1.8).

About 20 percent of American kids live in poverty, compared with 13 percent among all OECD countries on average. Part of the reason our kids are struggling is due to changes in family structure. Though the marriage norm has declined nearly everywhere, the U.S. holds the dubious distinction of leading the developed world in unstable adult relationships. We marry and cohabit at younger ages, and break up more often than adults in other countries. Our kids are more likely than others to be shuffled to different homes, forced to live with step-families, and separated from their fathers than others. This has taken a serious toll on children of all races and ethnicities. Child Trends reports that among non-Hispanic whites, the 2017 child poverty rate was 5.7 percent for children in married couple homes, but 32.7 percent for single-mother families. Among Hispanics, the rate was 14.8 percent for married couples, but 48.3 percent for single-mother families, and among African Americans, the rate was 10.3 percent for married couples and 43.2 percent for single-mother homes.

Clearly, a return to the two-parent norm (updated to include same sex marriages) would be ideal. But that is a complicated cultural matter that governments have limited capacity to affect—except, as the Romney Family Plan envisions, we can at least stop doing the things that penalize marriage. Our system of getting aid to children is convoluted, involving multiple state standards along with more than one tier of federal assistance and involving the IRS, USDA, HHS, and many more agencies. Because we Americans love to disguise spending as “tax policy,” we offer a “child care tax credit” along with a child allowance included in the Earned Income Tax Credit. The poorest families receive TANF. The way the EITC is structured, an analysis for the Niskanen Center demonstrates, can cost couples between 15 and 25 percent of income if they marry. This disincentive may have contributed to the marked decline of marriage among the working class in recent years. Also, the child care tax credit, which the Biden administration’s proposal would expand, serves as a pass-through to increase prices for providers without helping the average family choose the kind of relative-provided or local childcare arrangements that most families prefer. It also preferences paid day care over parental care.

The Romney proposal would sweep away TANF, the tax credits, and the rest in favor of a simplified and more generous child allowance of $4200 per year for children up to age 6, and $3000 per year for children ages 6-17. It would be available to all families with incomes up to $200,000 for single filers and $400,000 for joint filers (but has caps so that families with more than 4 kids will have to make do).

Conservatives worry about the disincentive to work inherent in traditional welfare programs, which is a reasonable fear. We don’t want to subsidize dependency and tax productivity. But part of the old “poverty trap” was not the child allowance per se but the implicit high marginal tax on earnings as parents re-entered the workforce. Niskanen points to Canada’s experience with a direct child allowance, finding that labor force participation actually increased after their child allowance was increased in 2016. Putting more money in the hands of parents permitted some mothers to return to work.

Another benefit of Romney’s approach is that it respects the wishes of parents. There’s a weakness on the left for the idea of clean, bright daycare centers staffed by Ph.D.s, producing happy and well-socialized boys and girls, and permitting mom and dad to go off to their rewarding jobs. But a quick glance at the local public school should be enough to raise doubts about the supply of “high quality” care. In fact, most daycare arrangements are far from ideal. However desirable it might be, you can’t get Ph.D.s to supervise toddlers at the prices our society is willing to pay. Here again, Canada’s recent experience is instructive. Quebec instituted a $5-per-day universal day care in 1997. The number of families placing pre-schoolers in care jumped by 33 percent. But a study published in 2015 by the National Bureau of Economic Research found some disturbing results: Compared with kids from other provinces, Quebec’s kids were less healthy and less satisfied with life. Most strikingly, Quebec experienced a spike in crime among the teenagers who had been in daycare as children.

The direct child allowance gives parents the flexibility to make decisions about care. Some will use professional daycare centers, others will opt for help from relatives and friends, and still others will use the extra income to permit one parent to stay at home while the kids are little.

Romney’s proposal is also pro-life. Family incomes tend to decline in the second half of pregnancy, so Romney’s child allowance would begin four months before a child’s birth. According to the Alan Guttmacher Institute, some 28 percent of abortion patients cite financial worries as one of the reasons for terminating a pregnancy.

Poverty isn’t good for anyone, but arguably child poverty is more damaging to society than any other kind. It stunts children’s development and blights their chances of reaching their potential. An Institute for Social and Economic research paper found that for every 1 percent increase in unemployment during the Great Recession, there was a 25 percent increase in child neglect. This effect was muted in states with more generous safety nets. We can only guess at the suffering the COVID-19 pandemic has caused.

Niskanen estimates that Romney’s proposal would reduce child poverty by one third and cut deep poverty in half. It would accomplish this without adding to the deficit, since the proposal contains offsets (specifically, eliminating the state and local tax exemption that mostly benefits wealthy individuals in high tax states).

This is what policymaking is supposed to look like. With any luck, Romney’s proposal will at least spark debate on a critical challenge for our country. A few years ago, that would have been normal. In 2021, it would be nirvana.