Motion Smoothing Is an Abomination

The aesthetic—and moral—reasons you should turn off your TV’s most-annoying feature.

Now that we’re all trapped in our homes, we have been pressed into service as our own chefs, hair stylists, and movie projectionists. I cannot help with the other two (I don’t cook and am bald), but I am here to help you with your streaming movie presentation. Here’s my number-one suggestion: turn off your television’s motion smoothing setting. It’s wrong for technical, aesthetic, and moral reasons. And you’re doing a disservice to yourself, your guests, and your favorite artists by leaving it on.

When artists create a movie, it is carefully designed to run at a certain light level and with calibrated color. But for marketing reasons, television manufacturers have an incentive to push the brightness and color saturation well outside these calibrated bounds. This has the obvious effect of making the movie brighter and more saturated than it was supposed to be, but it creates a new sneaky problem with motion.

Almost all movies and dramatic television are created using the standard frame rate of 24 frames per second. This is a very low frame rate relative to people’s vision, which isn’t really fooled into thinking it’s seeing real-life motion until the frame rate goes above 120 frames per second. But the choppiness of this low frame rate is greatly reduced if the light level on screen is lower. In fact, there is an upper limit to the permitted brightness on movie theater screens for this very reason. When images are presented too brightly, the 24 frame-per-second flicker, also known as “strobing,” will cause a lot of discomfort.

So now there is a problem: TV manufacturers want a brighter image from sets displayed on shelves at Target and Best Buy, often ten times brighter than the intended level for movies. This helps catch the eye of would-be customers. However, the resulting images will hurt their prospective customers’ eyes, which is considered a bad idea. Their solution to this problem is to layer another technical fix on top of the already misadjusted brightness and color: motion smoothing.

The basic idea behind motion smoothing is simple: we have 24 movie frames for every second, and we need more, so we make more. The television thus creates five “frames” from every real frame of the movie. To do this, the images on a series of adjacent frames of the movie are studied by the computer in the television to look for objects moving in different directions at different speeds. If the same object is seen from one frame to the next, the computer will create frames in between that animate that object from one position or pose into the next. This creates a 120 frame-per-second output ready to go to the screen. This kind of processing is called an “optical flow” algorithm, and it is used in machine vision, video compression, and other computational imaging applications.

The technical problem with this technique is that it is, basically, bonkers. The real world is not composed of simple objects sailing across the screen uninterrupted and with perfect clarity for the computer to detect and animate. When objects on screen pass in front of other moving objects, the processing will often fail to properly render the point of intersection, with both objects “melting” into each other rather than passing. Mathematically speaking, this class of algorithm is referred to as an “ill-posed problem,” meaning there can be no uniform solution. More simply, there just is no way to reliably create more data than you started with. Often the resulting motion is just very strange.

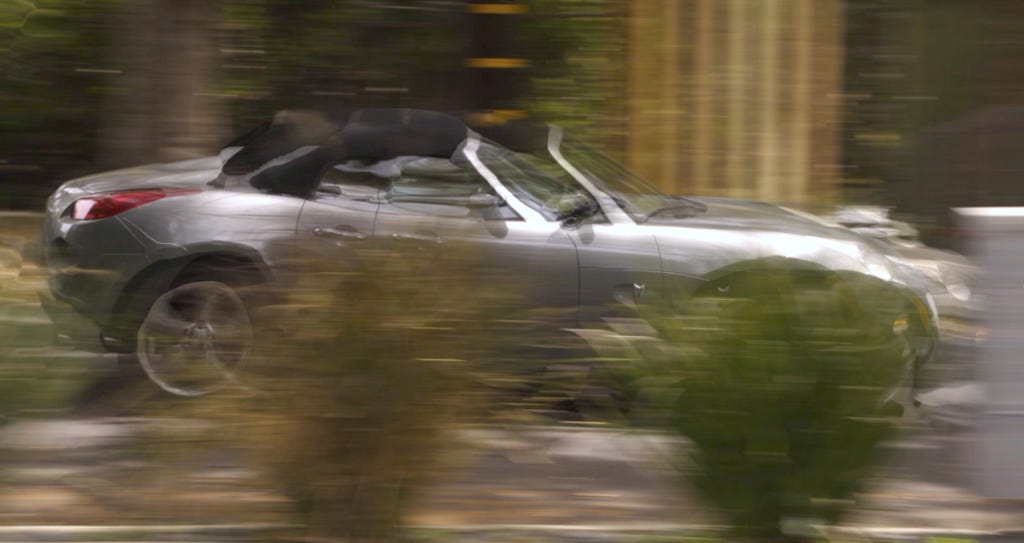

The computer in our television has to do two things: cut the images up into different objects and then try to figure out how to animate each of these objects to create new “frames” between the real frames of the incoming movie. This process is very much like cutting pictures out of a magazine and then moving them around by hand, except that it is being done by a computer with no real-world understanding. This can lead to horrific and sometimes amusing errors. A very simple example is to have one object moving in front of another. The computer will very often get confused by this, because it’s difficult to figure out which objects were destined to go in front of other objects, and then the animation of these pictures has to take into account the overlap. In the original footage here, the car is passing behind some bushes and a mailbox:

A frame of footage showing a car passing behind some bushes. Image credit: Bill Bennett ASC.

When the motion smoothing algorithm tries to understand this picture, it fails spectacularly to figure out which parts of the image are bushes (moving rapidly to the left) and which parts are the car (stationary with respect to the picture).

The motion-smoothed frame created by trying to estimate motion in the image. Image credit: Bill Bennett ASC.

The car is split apart and melted as the computer flails around trying to figure out this scene; the result looks a bit like a car if John Carpenter’s Thing had tried to mimic it. In short, this is a technically impossible problem for every possible real-world situation, even this very simple one, and any fully-automated motion smoothing system is guaranteed to have difficulty.

For the sake of argument, let’s pretend the motion processing algorithms worked perfectly. In fact, for many scenes, motion smoothing does its technical job reasonably well, and clever engineers have hidden the worst of the mathematical problems under layers of if/then rules. The end result is a very high frame rate, smooth image with no strobing.

The problem is that this will change the underlying feel of the movie dramatically, stripping away a “veil” that had previously been in place between the real world and the action of the movie. It reduces the fantasy and sweeping cinematic language into a made-for-tv documentary, dramatically changing the emotional impact of the material. This is sometimes called the “soap opera effect”: Soap operas were traditionally shot to videotape at 60 frames-per-second, rather than film at 24 frames per second like almost all other dramatic television. The pejorative nature of the phrase—soap operas are cheap and tawdry by their very nature—and its widespread application to this “advance” should tell us everything we need to know about the real-world impact of motion smoothing.

But, again for the sake of argument, let us assume that the technology works perfectly and the viewer is enjoying the ultra-smooth computer-generated images. I still argue the motion smoothing should be disabled because it distorts the artistic intent of the content. While 24 frames per second has been the standard frame rate for over 100 years, current filmmakers could choose a different frame rate if they wished, and some have (see: Ang Lee’s Gemini Man or Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk). But mostly the standard frame rate is chosen because it has an important role in the language of cinema, and it was the choice of the filmmaker to use it in their art. Further, if they wanted to use motion smoothing for streaming, they could do so in a supervised way prior to the streaming service sending it to the viewer. But they don’t. It’s very much like colorizing black and white movies: it’s a distortion of the artist’s vision without their consent.

So what are you to do? Well, in most televisions it can be turned off in the picture settings. Different vendors have different names for the option, and sometimes it’s easiest to just Google your model’s options. But this brings up another point: why in the world do these televisions have so many options? The televisions are all calibrated for brightness and color at the factory, and it would be possible for them to be fully calibrated with no adjustments whatsoever except for overall brightness, which could be pretty automatic.

There is hope for the future, however. Many televisions already have some sort of calibrated movie mode you can select, but there’s even better news coming. The UHD Alliance has put together something called “Filmmaker Mode,” which will set all the color and motion settings to calibrated levels to reproduce movies as close to the filmmaker’s intent as possible. There are many vendors who have signed on to this initiative, and soon we’ll see systems advertising this mode.

In the meantime, everyone is left to sorting through manuals and websites to try to get the settings right. If you’re serious about good image quality, I highly recommend getting a calibration Blu-ray disc and using it to adjust the settings correctly. One very good option is the Spears & Munsil Disc, and they have a new HDR UHD Blu-ray version available as well. These won’t help you get motion processing turned off, but they will help get the brightness correct so that the strobing won’t hurt your eyes.

Happy viewing!