My Confederate Past

Everyone who grew up in Mississippi was steeped in the Confederacy. Even if they didn’t realize it.

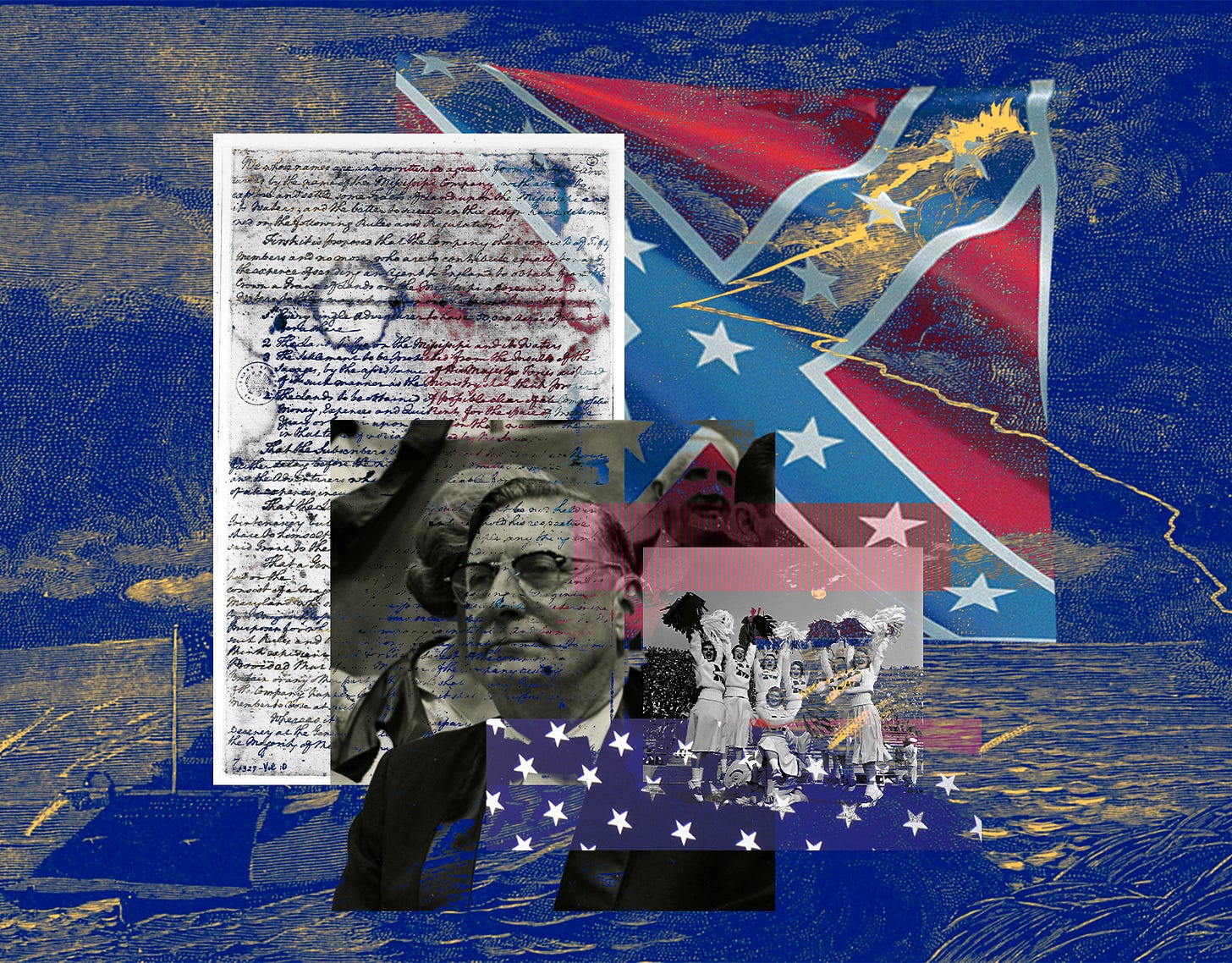

On Friday, the Mississippi legislature is scheduled to vote on changing the Mississippi state flag. As I write this, I have no idea what the outcome will be. On the off chance you’re unfamiliar with the Mississippi flag, it resembles the American flag—except the upper-left quadrant is the Confederate battle flag. It was adopted in 1894 at the height of the white backlash to Reconstruction.

It’s difficult to explain to a non-Southerner the role the Confederate flag has played in our lives. I suspect that’s more so for a Mississippian than for someone from any other state as Mississippi is the most Southern of the states. Put it this way: If you have connections to the University of Mississippi—the most Southern school in the most Southern state—then your connection to the Confederate flag is what the shamrock is to Notre Dame.

I was born in the 1950s to parents who met at Ole Miss. The role Ole Miss football played in my life was basically what the Catholic Church is to the Jesuits. It was both a belief system and the organizing principle of life. Saturdays in the fall were the Holy Days when the Faithful would gather and reinforce our devotion through the shared communion of ritual.

These were not football games but celebrations of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy. Only this time our 11 soldiers on the field of battle more often than not emerged victorious. At halftime the band marched in Confederate battle gray uniforms while Colonel Reb led the cheerleaders in unfolding what was billed as the world’s largest Confederate flag. (Even as a 10-year-old I remember wondering, “How big was the second-largest flag?”) Cheerleaders threw bundles of Confederate flags into the stands. We stood and swayed together singing Dixie, always ending in the stadium-shaking cry, “The South Shall Rise Again.”

It was at halftime in the 1962 Ole Miss-Kentucky game at Jackson’s Memorial Stadium—walking distance from my home—that Governor Ross Barnett gave his famous speech calling for states’ rights. We beat Kentucky that afternoon and the next day in Oxford there began the last pitched battle of the Civil War. It took 30,000 troops to force the University of Mississippi to accept a single black student

Today you’re more likely to get a student riot if a top-ranked black athlete committed to Ole Miss and then switched at the last minute to Alabama.

The Confederate flag was everywhere then, from bumper stickers to bikinis. And yes, on the state flag. I’m here to confess that I never really thought much about the Mississippi state flag until, well, this century.

It was just always there; like the way the magnolia was the state flower and Mississippi State had those awful cowbells. At school we pledged allegiance to the U.S. flag and the state flag and it never occurred to me that we were still pledging fealty to the Confederacy. I came from a family of lawyers, judges, and Methodist ministers, not plantation slave owners.

My grandmother was a founding member of the Mississippi chapter of the Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching—yes, there was such a thing and a horrifying need for it—but the Confederacy was still part of my life. I was named for an uncle who was named for Jeb Stuart. I grew up knowing that the Fourth of July was Independence Day, yes, but also the day both Vicksburg and Gettysburg were lost. Recently a cousin found a photo of me dressed in a Confederate officer’s uniform at an Old South Ball at the Jackson Country Club.

I think I was 13.

Mississippi has the highest percentage of African Americans of any state in the country. I ask myself now why did it take so long for me to realize what it might be like for nearly 40 percent of my state to go to school and work under a flag that represented a cause dedicated to the right to own their ancestors? Why is it that I had written books about traveling through China, Africa, and Europe, fascinated by every cultural quirk I came across, before I looked up at my own state flag and thought about the dehumanizing brutality it represented?

I don’t have any good answers, most likely because there are none. I was given every opportunity in this life, an open door to the world, a chance at the best education in the United States and England, a family that supported my odd passions that I was lucky enough to turn into professions. I had passport stamps from 61 countries with different flags before I began to think about my own state’s flag. It wasn’t that I was actively for the flag . . . but that indifference was just as toxic as active support.

Today many white Mississippians of my generation—and even more of the younger generation—are eager to change. Faulkner wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” We can’t undo what we didn’t do.

But my regret is mixed with a hope. Hope that perhaps we can take steps—small and inadequate as they might be—to face the truth of our Confederate past. And in doing so change the future.

It will never be enough. But I hope today we can take one more step out of the shadows of a bloody past into the brighter sun of a better day.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Ole Miss defeated Arkansas, when they played Kentucky.