My Father and the Birth of Modern Conservatism

The inspiration for the 1964 “Extremism in the defense of liberty” speech he wrote for Barry Goldwater.

ON JULY 16, 1964 BARRY GOLDWATER STRODE to the podium at the Cow Palace in Daly City, California and accepted the Republican party’s nomination for president. “Extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice,” he famously said. “Moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.” Modern conservatism was born.

Harry Jaffa, a college professor of political science, liked to say that those words would have ended any chance Goldwater had at a victory—if indeed he had had any chance. (He did not, of course, just months after the assassination of JFK.)

Certainly Jaffa ought to know. He wrote those words—along with the rest of the speech.

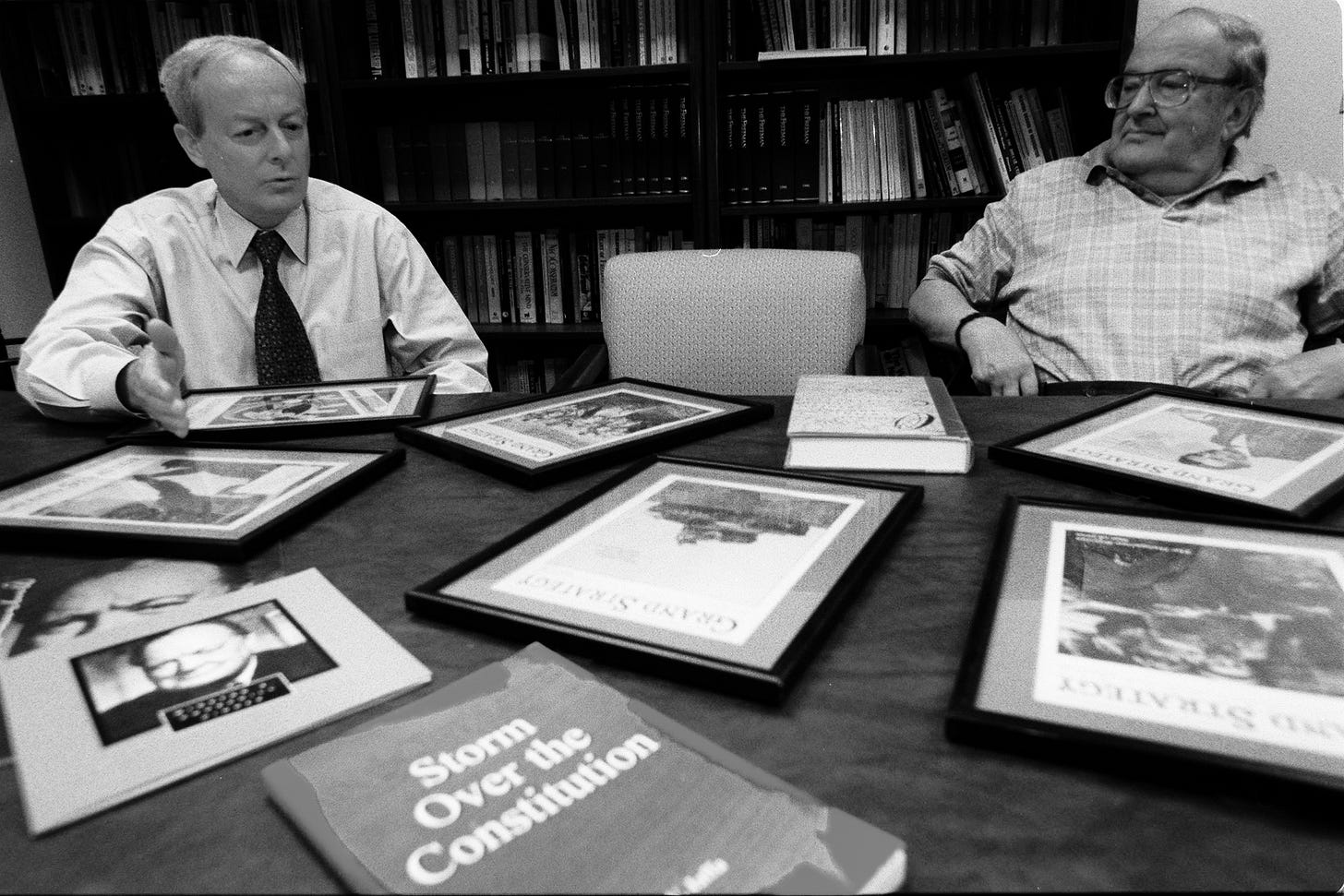

Harry Jaffa was my father. I was only 12 at the time, but I clearly remember the excitement following the convention. The first thing my father did when he got back was grab me and go down to City Hall to register as a Republican. He swore me to secrecy. He did not want it to get out that Mr. Republican’s acceptance speech had been written by a Democrat.

The impact this speech had on my father’s life was profound. In my father’s words, he went from being an obscure professor of political science whose teachings were ignored to a famous professor of political science whose teachings were ignored!

The speech my father wrote for Goldwater had two purposes: a tangible political objective and a great philosophical goal.

The Republican party in 1964, like most political parties, was a collection of different groups with differing goals and objectives. Many of them my father considered unsavory. The differences among the party’s factions sometimes seemed as large as the difference between Republicans and Democrats. My father thought that if the core mission of the Republican party could be reduced to two things—fighting communism abroad and socialism at home—that the conservative movement would coalesce and ultimately be victorious.

“Back in 1858,” said Goldwater, “Abraham Lincoln said this of the Republican party—and I quote him, because he probably could have said it during the last week or so: ‘It was composed of strained, discordant, and even hostile elements.’ . . . Yet all of these elements agreed on one paramount objective: To arrest the progress of slavery, and place it in the course of ultimate extinction.

“Today, as then, but more urgently and more broadly than then, the task of preserving and enlarging freedom at home and of safeguarding it from the forces of tyranny abroad is great enough to challenge all our resources and to require all our strength.”

This is exactly what happened. The Republican party did coalesce around the idea of fighting communism abroad and socialism at home, and a rising conservative movement in time would elect Ronald Reagan president.

What followed next was equally remarkable.

The Soviet Union collapsed and the Democratic party abandoned of the idea of a centrally planned economy.

In the words of my father, never before in human history had two mortal enemies confronted each other, and one defeated the other not by force but by persuasion, and did so in such a way that both the victor and the vanquished were better off.

Reagan did it . . . twice!

Here are a few lines from that 1964 speech that certainly look prescient today:

I believe that the communism which boasts it will bury us will instead give way to the forces of freedom. And I can see in the distant and yet recognizable future . . . the whole world of Europe reunified and freed, trading openly across its borders, communicating openly across the world.

But, as my father liked to say, there are two things that are absolutely guaranteed to destroy a political coalition. One is defeat. The other is victory. When the Berlin Wall came down, the Republican party immediately began transforming itself back into its familiar “strained, discordant, and even hostile elements.”

My father also had a philosophical objective in the writing of that speech—one that might have precluded the splintering of the GOP. He sought to shift the Republican party onto the bedrock principles of Abraham Lincoln and the American Founding—onto the natural law teaching of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. But, as my father ruefully observed on many occasions, he put words into Barry Goldwater’s mouth that Goldwater never would have said if Goldwater had known what he was saying.

And that, ironically, includes the famous assertion that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice . . . and moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.

Those lines were a literary allusion to Martin Luther King’s letter from a Birmingham Jail, which my father had recently used in class—and of course the Pledge of Allegiance (“liberty and justice for all”).

My father wrote Goldwater’s speech in a classic all-nighter, on an old, manual portable Royal typewriter, hunt-and-peck (he did not learn to touch type until after I bought him a computer). He had no books or reference materials with him. But he had committed to memory these memorable lines from King’s letter:

But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: “Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you.” Was not Amos an extremist for justice: “Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever flowing stream.” Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: “I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus.” Was not Martin Luther an extremist: “Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God.” And John Bunyan: “I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience.” And Abraham Lincoln: “This nation cannot survive half slave and half free.” And Thomas Jefferson: “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal . . .” So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be.

The world had reached a tipping point. It could not survive half communist and half free. It was time for America to embrace the idea of extremism. And that for which they should be known as extremists was an unshakable commitment to “liberty and justice for all.”

My father knew that had he so much as breathed the name of Martin Luther King in Republican circles his own name would have been mud. Even when a group of conservatives who did not like my father began circulating nonsense about those lines being cribbed from Cicero my father kept his counsel. All he would say was that the Cicero story was false and that the words were his.

Nevertheless, with a twinkle in his eye, at the tail end of his life, he liked to say that for more than five decades he had had the pleasure of watching the left wing of the Democratic party denounce the views of Martin Luther King—a man they worshiped and idolized—while the right wing of the Republican party embraced the views of Martin Luther King, a man they loathed and despised.

As for the reference to the Pledge of Allegiance, you might think that nothing is less controversial among conservatives than that. And, in a sense, this is so. The Pledge of Allegiance is an expression of patriotism—and if there is one thing American conservatives are proud of, it is their patriotism.

However, in the opinion of my father, the Pledge of Allegiance also is something that conservatives say without understanding.

My father’s scholarly introduction to the Pledge of Allegiance began in 1954, when Congress added the words “under God.” At the time, my father, in his mid-thirties, was studying Lincoln and was intrigued by the press accounts of that alteration of the Pledge. By tradition, American presidents would celebrate Lincoln’s birthday by attending Lincoln’s Church (New York Avenue Presbyterian)—sitting in Lincoln’s pew on the Sunday closest to Lincoln’s birthday. On February 7, 1954, President Eisenhower had sat in Lincoln’s pew and listened to a sermon on the Gettysburg Address—a sermon entitled “A New Birth of Freedom,” which included a call to add the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. Eisenhower became an instant convert. Within months, by act of Congress, “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom” (from the Gettysburg Address) became “one Nation, under God, indivisible” (in the revised Pledge of Allegiance).

This inspired my father to begin researching the origins of the Pledge of Allegiance. He was delighted to find out that the author, Francis Bellamy, attributed the word “indivisible” to the speeches of Abraham Lincoln and Daniel Webster, and saw the Pledge as a distillation of the principles of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Union side in the Civil War. The Pledge of Allegiance, on its surface, was aimed at schoolchildren—especially the children of immigrants. It was also aimed at Southerners and the doctrine of states’ rights (“indivisible”). Indeed, the very idea of a “pledge of allegiance” appears to have come directly from the “loyalty oath” that Lincoln made Southerners say in order to regain their right of citizenship.

On June 10, 1964 (after a 57-day filibuster), the critical vote occurred in the U.S. Senate to invoke cloture and move forward on the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. Barry Goldwater was one of only six Republicans who voted no—a move that helped turn the old South into the bastion of the Republican party.

Thirty-six days later, while the audience went wild at the Cow Palace at “extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice” (and conservatives everywhere took up the call), my father slyly placed Goldwater on the shoulders of Martin Luther King and the idea that an oath of allegiance was required of Southerners.