How Rusty Reno Infected First Things

The magazine First Things has become a zombie version of itself as the Catholic rad trads try to justify Trumpism.

1. Coward Masks

I finally put together my thoughts on the subset of people who insist that we must open America up right now, but that they refuse to wear masks.

The piece is here. You should read it.

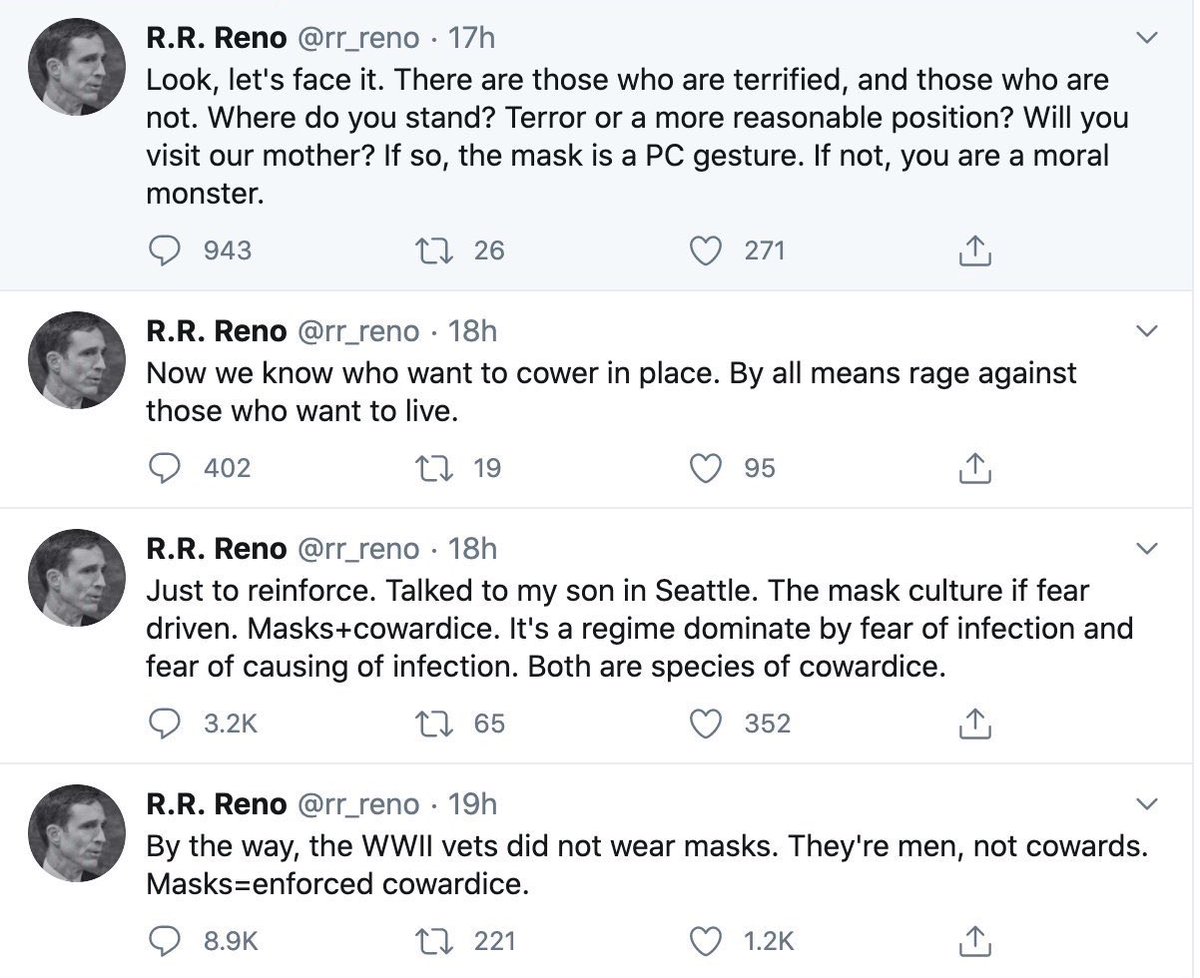

As I was writing it, R. R. Reno, the editor of First Things, threw a Twitter tantrum about masks. In case you didn’t see it:

Reno has since deleted these tweets, without either explanation or apology. If you were going to be charitable you might say that he is ashamed of himself. If you were going to be realistic, you might say that the fellow casually accusing others of being “cowards” is less than stalwart himself.

I don’t want to talk about this in the context of the mask culture war, because Reno's assertion has already been thoroughly torn apart: It’s wrong as a factual matter (soldiers absolutely wore masks), as a prudential matter (you wear a mask not to protect yourself, but to protect others), and as a moral and metaphysical matter (taking reasonable steps to prevent unnecessary deaths is not evidence of a disregard for eternal life).

I don’t even want to talk about the hypocrisy of the man who once lamented how “people need guardrails” and how unfortunate it is that “we’ve dismantled a lot of the guardrails in our society” now raging against simple, temporary public health guidelines in a time of pandemic.

Instead, I want to talk about Reno himself and what he has done to a once-great magazine, First Things.

Magazines of ideas rarely outlive their founding editors in any meaningful way. There are exceptions: National Review, the New Republic, and Commentary are the three great ones of our time. But in general, the founding editor is the main source of intellectual energy in the enterprise. Without him, the magazine stalls or loses its way.

In a funny way, the closest analogy I can make for people outside the journalism world is the big-time college sports coach. When a Bobby Knight or Bobby Bowden steps away, very few programs are able to maintain a level of excellence in the medium-term, let alone the long-term.

Rusty Reno was hired to run First Things in 2011. He had previously been associated with the magazine as an occasional contributor, then briefly as its “features editor” before stepping back to just a nominal affiliation. He was a college professor who had not run a magazine before and brought with him no ideas on what to do with the institution that was entrusted to his care. I offer this judgment as a longtime First Things reader who dutifully slogged through its pages every month. But if you'd like a more objective proof, consider this:

Fully two years after taking the helm at First Things, Reno ran a symposium in which he plaintively asked outside writers to come up with some idea for the future mission of his magazine.

Reno’s own contribution to this symposium was embarrassingly anemic. He concluded by saying:

I don’t pretend to know how to respond adequately to these challenges, if indeed I have properly identified them in the first place. But I am convinced that the context for our witness is shifting in important ways. That won’t mean that First Things changes what it stands for, but it may, perhaps necessarily will, change where we stand.

This piffle is not the product of a mind suited to leading a magazine of ideas. It is, if anything, an admission of a lack of editorial vision.

In the course of this symposium, the most clear-eyed and vigorous proposal for what the magazine should be came from occasional contributor Eric Cohen.

He never wrote for First Things again.

While Reno lacked a strong intellectual point of view, he does possess a sensibility: Like many professors, he has a performative streak and he seemed drawn to the outré. In conservative Catholic circles, this means radical traditionalism. Without really meaning to, First Things became a gathering place for rad trads, where they could posture and preen.

This was unfortunate, and a little sad, but ultimately harmless enough.

2. Trump and the Rad Trads

Then came Donald Trump.

After some equivocation—he was against Trump, then for Trump, but then after the Access Hollywood tape, he scurried away from Trump, even deleting a pro-Trump podcast he had recorded, before finally poking up his head again—Reno came to embrace Trump. In fact, the ascendance of Trump to the godhead of conservatism seems to have given Reno the Big Idea he had been casting about for during the early years of his editorship. And so Reno and First Things set about trying to build an intellectual framework around Trumpism.

This has proved impossible because Trumpism is Trump and Trump the man has no coherent intellectual framework beyond immediate self-interest.

(As an intellectual exercise, it might be possible to build some sort of reformed conservatism apart from Trump that left behind the fusionism of the Reagan years. There are some professional conservatives who are trying to do that right now. The problem with this project is that it necessitates either criticizing or ignoring Donald Trump. Doing the latter is unserious. Doing the former renders you radioactive inside Conservatism Inc.)

After three years of groping and straining to codify Trumpism into an intellectual movement, First Things came up with a manifesto, “Against the Dead Consensus,” that was little more than emo sentimentality. Again and again, this “common-good conservatism” that First Things has agitated for under Reno has been exposed as being ill thought out—little more than inchoate mush.

One of Reno's most shocking admissions about this mushiness came in the course of an interview with the Atlantic:

When I asked Reno about the president's comments referring to Mexicans as rapists and criminals, and the family-separation policy that left dozens of migrant children stranded in government vans for 24 hours or more, Reno replied, “I don't do policy, but if we don't gain control of the border, it’s going to be a serious problem for the entire generation.”

“I don’t do policy” says the editor of an intellectual magazine as he reorients it to become a political enterprise centered on defending and justifying the politics of Donald Trump.

The coronavirus pandemic has liberated Reno to give full flower to his feelings as he rails against policies he dislikes.

Before his tweets calling people who wear masks cowards, he wrote a series of essays calling the mitigation efforts used to keep the COVID-19 death toll to the low six-figures “demonic.” Leave aside the hypocrisy of a man who “doesn’t do policy” weighing in on highly specialized matters of public health policy: This was one of the most breathtakingly irresponsible actions I have ever seen from a magazine editor.

But it is not the most irresponsible thing Reno has done this month.

In his most recent “Coronavirus Diary,” Reno declares that he has tested positive for COVID-19 antibodies, meaning that at some point in the recent past he had been one of the asymptomatic carriers capable of passing the infection on to others. In the same column, he brags about sneaking into an emergency room a few weeks ago—against hospital policy—in order to interview a doctor. (Could this doctor not have been interviewed in any other setting?)

I wonder if, during this excursion, Reno was contagious.

And if he was wearing a mask.

3. Commercial Real Estate

The ripples from the pandemic go to the horizon, even if you only focus on the United States:

Before the coronavirus crisis, three of New York City’s largest commercial tenants — Barclays, JP Morgan Chase and Morgan Stanley — had tens of thousands of workers in towers across Manhattan. Now, as the city wrestles with when and how to reopen, executives at all three firms have decided that it is highly unlikely that all their workers will ever return to those buildings.

The research firm Nielsen has arrived at a similar conclusion. Even after the crisis has passed, its 3,000 workers in the city will no longer need to be in the office full-time and can instead work from home most of the week.

The real estate company Halstead has 32 branches across the city and region. But its chief executive, who now conducts business over video calls, is mulling reducing its footprint.Manhattan has the largest business district in the country, and its office towers have long been a symbol of the city’s global dominance. With hundreds of thousands of office workers, the commercial tenants have given rise to a vast ecosystem, from public transit to restaurants to shops. They have also funneled huge amounts of taxes into state and city coffers.

But now, as the pandemic eases its grip, companies are considering not just how to safely bring back employees, but whether all of them need to come back at all. Read the whole thing.