One Chart Explains Why COVID-19 Is Worse Than the Flu

COVID-19 is much worse than the flu. Anyone who says otherwise is either lying, or does not know what they are talking about.

1. Science Talk

By now you have probably seen people explaining that, "Actually, the coronavirus pandemic is not much different from the flu and all of this fuss is just a big overreaction."

Or, "More people die in car accidents every year and you don't see us shutting down auto travel, you big bunch of ninnies."

It's hard to know whether these arguments are just partisan bs meant to alibi Donald Trump, or if they are serious beliefs resulting from a misunderstanding of data.

For a moment, let's pretend it's the latter.

This piece in the New Atlantis by my friends Ari Schulman, Sam Matlack, and Brendan Foht is one of the best, most helpful, and important pieces to be published about the pandemic.

But in case it's a little more data-driven than you're used to, I want to walk you through it here.

One of the mistakes being made by people who think that COVID-19 is "just like the flu" is that they don't actually understand the reported death numbers for either virus.

The number most often cited for annual flu deaths is 60,000. This number is a composite. It includes a relatively small number of deaths directly ascribed to influenza (meaning, there was a positive flu-test involved) PLUS a much larger number of deaths from pneumonia, where it is assumed that because flu-like symptoms were present, the influenza virus was likely at play.

This is the exact opposite of how we've been tabulating COVID-19 deaths.

So right from the beginning, the COVID-19 and flu death numbers are apples and oranges:

The "flu death" numbers are mostly deaths that we assume are related to influenza, even though only a small minority of them were proven to have influenza present.

The COVID-19 numbers are made up only of deaths that have an accompanying positive test for coronavirus and leave out deaths from COVID-19 like symptoms.

That's the measurement problem. There are other problems, too, which have to do with the rate of infection.

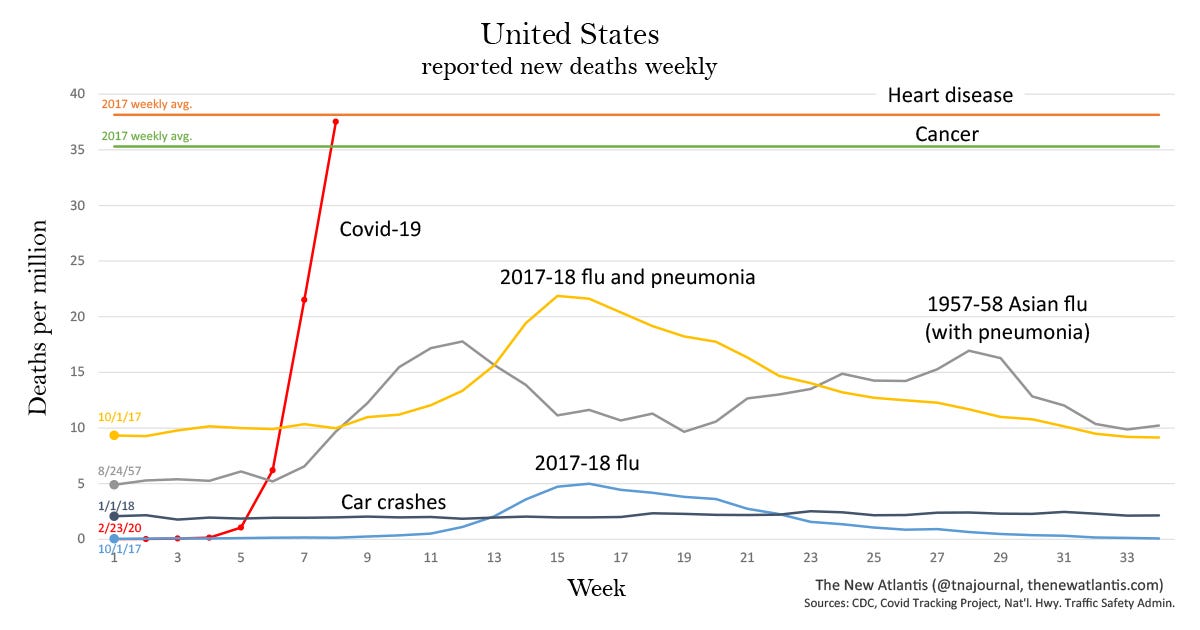

Take a look at this graph and you should understand why COVID-19 is fundamentally different from the flu:

Now you get it, yes?

The light blue line along the bottom represents new weekly deaths from the deadliest flu season in recent times (the 2017-2018 flu).

The yellow line shows the new weekly deaths from that flu season plus deaths from pneumonia—which is that composite number we were just talking about.

And the red line is COVID-19.

Now, look at how steep the yellow curve is when it first begins inflecting around Week 13.

And then look at how steep the red curve is at Week 5.

This is why we shut the country down.

(1) The absolute magnitude of weekly deaths for COVID-19 was already bigger than the largest magnitude for the entire flu season by Week 6 and by Week 7 was double the magnitude of the worst of flu season. And it was still increasing.

(2) That's if you compare COVID-19 to the composite yellow line. Go ahead and compare it to the blue flu-only line (since that's the better analog in terms of real tabulation of deaths) and we are already at 800 percent of the peak weekly death-rate.

(3) And this is with the imposition of drastic suppression methods.

Coronavirus is so much more dangerous to the American people than the flu that anyone who suggests equivalency is either deliberately lying, or does not know what they are talking about.

Give them this explainer, and then you'll know which is which.

2. February 2020

I am, by nature, a glass-half-empty guy. Perhaps you've picked up on that.

But I made a little note to myself on Friday, March 13. My kids' Montessori school was still open, but the public schools in our county had just closed. They insisted that they were merely "cleaning" the schools and that they would reopen the following Wednesday. I knew that this was a fantasy. And we kept our kids home on the principle that no one wants to be the last person infected before a quarantine.

I went to Costco for what I assumed would be the last time for a while and I was struck by how normal it seemed. Normal number of shoppers. Normal assortment of goods in people's carts. I was already wearing gloves and getting stocked up for the end of the world.

I had parked in a far corner of the lot, so as not to be too close to anyone else's car and as I pushed my cart back to our minivan I stopped for a moment and took in the scene. I knew that the next time I was back here, everything would be different. There would be lines and shortages. Everyone would be wearing masks. Several thousand Americans would be dead.

And the line that came to me was one made famous by Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Secretary who, on August 3, 1914—the evening before Britain entered the Great War—said to a friend, "The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time."

I knew we'd be luckier than Grey had been. But my sense then—which remains today—is that there will be no return to "normal" until we have a vaccine for the novel coronavirus. And even then, it will be a new sort of normal.

All of which is wind-up to say that you should read Bill Kristol's piece on how February 2020 marked the end of an epoch. It touches on all of these things and sums up almost perfectly my views on what we are living through.

3. Huckleberries

Tombstone is the great modern Western. No one denies this.

My friends over at Rebeller are running a series of pieces on the making of Tombstone this week written by actor Michael Biehn, who played the great Johnny Ringo. (Why Johnny Ringo. You look like somebody just walked over your grave . . .)

As production commenced, Michael noticed a curious dynamic unfold among the cast. In their off hours, they segregated into the same factions as their characters. Prior relationships held little weight here. For example, Tombstone was the fifth movie he had done with Bill Paxton (Morgan Earp); they’d met in London a decade earlier on Lords of Discipline. Yet on Tombstone they had dinner only once and called it an early night. He continued to bond with Powers Boothe and found kindred souls in fellow Cowboys John Corbett and Stephen Lang. Corbett was “really funny and clued in, we could keep up with each other well into the night,” he remembers. His overriding image of Stephen Lang, who plays hyperkinetic live-wire Ike Clanton, is of the actor spending hours practicing his cello. He proved to be a good sounding board for Michael’s thoughts about playing Johnny Ringo.

Tombstone had been shooting for some days when Michael started, and he quickly sensed disquiet and uneasiness about Kevin Jarre’s manner of directing. . . .

Near the end of the fourth week, Michael pulled Kevin into his trailer to try to help his director understand the obvious and growing disgruntlement. . . . [B]ut the die had been cast and he was fired the following Friday. . . .

Rumors swirled that weekend that the production might shut down. Michael soon learned, however, that producer Jim Jacks was holed up with Kurt Russell in a hotel room, amputating the screenplay while replacement director George Cosmatos rushed to Tucson. In a 2006 interview given after Cosmatos died, Kurt said he had warned Kevin that 20 pages had to come out of the screenplay and now he and Jim proceeded to do just that. According to Kurt, the way to hold the movie together while excising a big chunk of it was to eviscerate his own role. He and Jim then informed the cast what remained of their roles; Jim delivering the news to the Cowboys while Kurt advised the other Earps. Read the whole thing.