This Is How Kent State Happened

It's happening again.

1. Danger Zone

One of Donald Trump's . . . I don't know how to say this—strategies? impulses? pathologies?—is his ability to turn every issue and every question into a referendum on himself.

He did this trick with COVID-19 so completely that the pandemic became, as a political matter, just another front in the culture war.

He is now in the process of performing this same alchemy with the protest movement surrounding the murder of George Floyd. There is no reason—none at all—why these events should be about Donald Trump.

But he is desperately trying to take ownership of them and thus dominate them.

This may be good politics for Trump—or, more precisely, it may be the only move he has left on the board, even if it winds up hurting him down the line.

But it is bad for the cause of justice. Attempting to reform parts of the justice system are hard enough without turning them into a partisan kulturkampf.

And it carries the potential to be very, very bad for America. Because if the president of the United States is spoiling for a fight with the citizenry, he is likely to get one.

I cannot get past the parallels between what Trump has said over the last week and what Ohio governor Jim Rhodes said in a speech on Sunday, May 3, 1970:

The scene here that the city of Kent is facing is probably the most vicious form of campus-oriented violence yet perpetrated by dissident groups and their allies in the state of Ohio. . . . Now it ceases to be a problem of the colleges in Ohio. This is now the problem of the state of Ohio. Now we're going to put a stop this, for this reason. The same group that we're dealing with here today, and there's three or four of them, they only have once thing in mind. That is to destroy higher education in Ohio. . . .

Last night I think that we have seen all forms of violence, the worst. And when they start taking over communities, this is when we're going to use every weapon of the law-enforcement agencies of Ohio to drive them out of Kent. . . .

They're worse than the brownshirts and the Communist element and also the night riders and the vigilantes. They're the worst type of people that we harbor in America. . . . It's over with in Ohio. . . . I think that we're up against the strongest, well-trained, militant revolutionary group that has ever assembled in America. . . .

We're going to eradicate the problem, we're not going to treat the symptoms. The governor's speech was broadcast not only to the press and the voters, but was piped into the National Guard's bivouac on the campus of Kent State University.

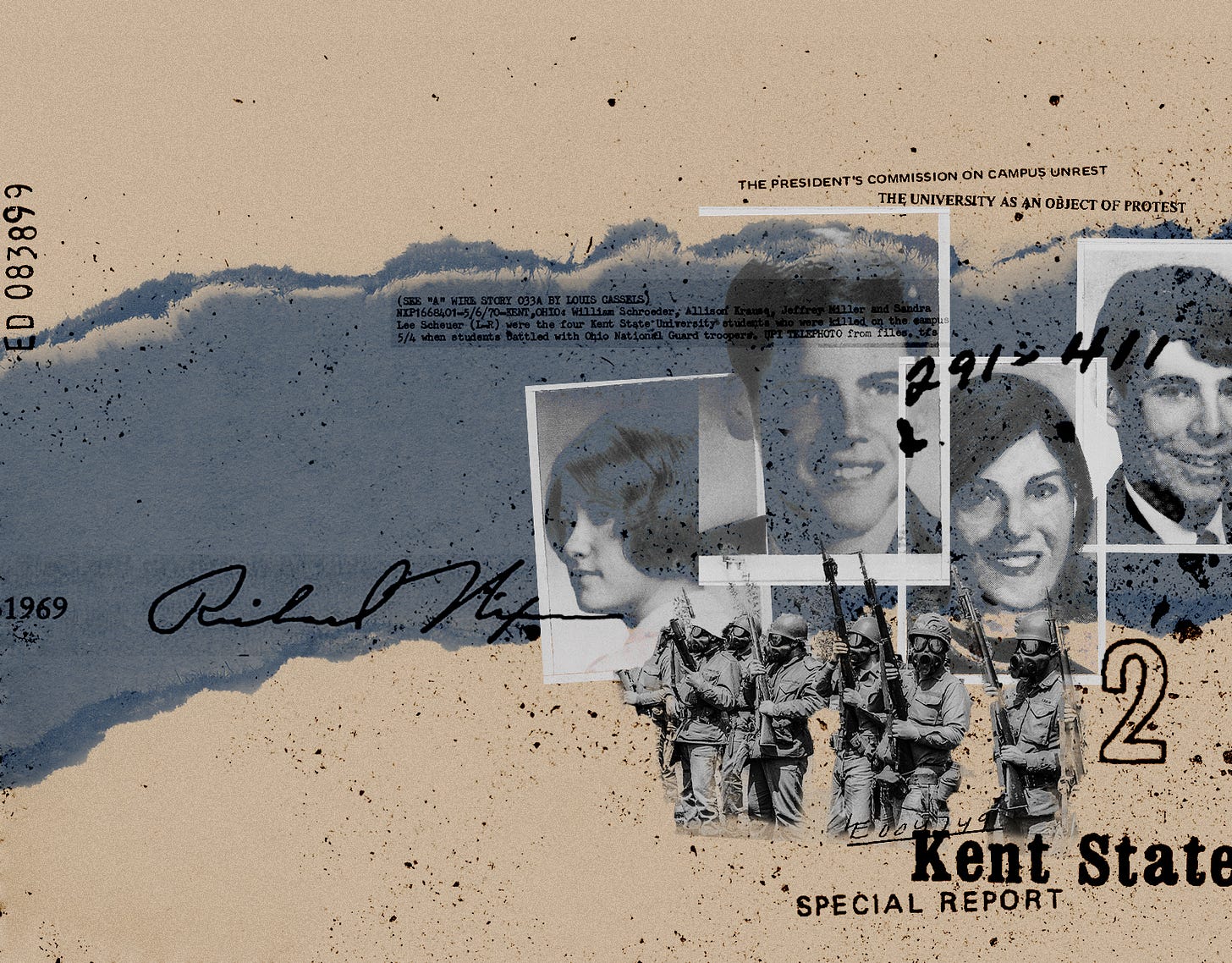

On the next day, May 4, 1970, a group of National Guardsmen fired indiscriminately into a group of unarmed students on the Kent State campus at a moment when the students presented no immediate threat. They killed four of the students and wounded nine others.

Kent State is a long time in the rearview mirror, so you may have forgotten exactly what happened and who was at fault. Here's the federal government's own conclusion about what happened that day, from The President's Commission on Campus Unrest:

The May 4 rally began as a peaceful assembly on the Commons—the traditional site of student assemblies. Even if the Guard had authority to prohibit a peaceful gathering—a question that is as least debatable—the decision to disperse the noon rally was a serious error. The timing and manner of dispersal were disastrous. Many students were legitimately in the area as they went to and from class. The rally was held during the crowded noontime luncheon period. The rally was peaceful and there was no apparent impending violence. Only when the Guard attempted to disperse the rally did some students react violently.

Under these circumstances, the Guard's decision to march through the crowd for hundreds of yards up and down a hill was highly questionable. [Note: The Guard literally marched against the students with fixed bayonets.] . . .

When they confronted the students, it was only too easy for a single shot to trigger a general fusillade. . . .

The actions of some students were violent and criminal and those of some others dangerous, reckless, and irresponsible. The indiscriminate firing of rifles into a crowd of students and the deaths that followed were unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable. . . .

Even if the guardsmen faced danger, it was not a danger that called for lethal force. Please understand that this is not the verdict of hippie history professors. These are the conclusions that came out of the commission set up by Richard Nixon.

So why did the Guardsmen take this unnecessary, unwarranted, and inexcusable action?

In part, because Gov. Rhodes had primed the pump by claiming that the students were a "well-trained, militant revolutionary group" who needed to be "eradicated."

Sound familiar?

This is where we are heading, right now. But at a national scale.

May God protect us.

2. What Did They Think Would Happen?

Almost two years ago to the day, this is what I wrote at the Weekly Standard:

My favorite scene in my favorite Tom Clancy movie is a little throwaway moment in The Hunt for Red October. The Soviet and American navies are jousting in the north Atlantic, with their exercises designed to provoke each other. An American F-14 goes careening out of control as it lands on a carrier and the commander, played by the late, great Fred Thompson, fumes, "This business will get out of control. It will get out of control and we will be lucky to live through it." . . .So let's follow the progression: Two weeks after Trump was elected, Mike Pence went to see Hamilton on Broadway and got a respectful talking to from the stage. There was a long pause on this sort of direct action until, last Tuesday, Kirstjen Nielsen was heckled as she ate dinner at a Mexican restaurant. Three days later, Sarah Huckabee Sanders went to dinner at a restaurant called the Red Hen and the owner asked her to leave. And on Sunday, Maxine Waters upped the ante by suggesting that rather than just ask Trump staffers to leave, citizens ought to mob them and shame them, Cersei Lannister-style, whenever they are seen in public.

This is a disgusting and appalling lack of civility and a departure from the norms of American political discourse and I cannot fathom where liberals got the idea for it and, by the by, here is a list of some things the current president of the United States of America said while campaigning for his office:

“I’d like to punch him in the face."

“Maybe he should have been roughed up.”

"Part of the problem . . . is no one wants to hurt each other anymore.”

“I don’t know if I’ll do the fighting myself or if other people will.”

"The audience hit back. That’s what we need a little bit more of.”

"If you do [hurt him], I’ll defend you in court, don’t worry about it.”

“I’ll beat the crap out of you.”

“Knock the crap out of him, would you? I promise you, I will pay your legal fees.”It's a mystery, isn't it? Where in the world did Maxine Waters and the Red Hen and the people in that Mexican restaurant come up with such terrible, norm-shattering ideas about civility? . . .

The reason we have norms in the first place is because there is always an undercurrent of violence in politics. And that’s because, to invert Clausewitz, politics is war by other means. One of the great accomplishments of Western civilization has been, for the most part, to push that undercurrent way down deep. It has not always worked. It will not always work.

Americans tend to look at a place like the former Yugoslavia and think that that sort of unpleasantness can't happen here. And maybe it couldn't. America has strong institutions, and institutions matter when it comes to keeping undercurrents of violence submerged. Though perhaps you've noticed that none of America's institutions—our governments, our churches, our civic organizations, our universities, our families—are as strong as they used to be.

Which is why so many people were prospectively worried about Trump. Not because Trump was the source of some new brand of political violence, but because political violence is a Pandora’s Box. And once it is opened it cannot be shut until it burns itself out—because everyone loves this sort of thing, when it's their side doing the scalping. Putting a man like Donald Trump in the presidency gave oxygen to these elements or, to mix our metaphors, pushed the undercurrents that have always been there much closer to the surface. As it turns out, we have not gotten lucky.

3. Offline

Wired looks at how some Minneapolis residents are going offline:

ON SATURDAY AFTERNOON, under a cloudless Minneapolis sky, thousands of people flocked to a 50-block stretch of Lake Street, where for the previous three days, mass protests over the police killing of George Floyd sparked riots and violent standoffs with police and National Guard. Some came with brooms and buckets. Some drove trucks full of freshly cut plywood and portable drills for boarding up the businesses that were left. Many carried hand-painted signs saying “Stop killing black people” and “Justice for George.” Almost everyone wore a mask. And everywhere you looked, people were pointing cell phones—capturing protesters chanting, citizens sweeping up broken glass, and buildings still smoldering for audiences on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook to see.

At a gathering a few blocks to the south in Martin Luther King Jr. Park, the ground rules were very different: no livestreaming, no social media posts, only share things directly with people you trust. It may have seemed a bit paranoid to the 300 people, mostly white families and retirees, who had shown up to participate in a neighborhood defense planning meeting. But then again, scores of shops, restaurants, and community bulidings in the city had been damaged or set on fire in the past 24 hours. And they had reason to believe that this night would be even worse.

That morning, Minnesota governor Tim Walz had claimed during a press conference that highly organized outside groups, including white supremacists and drug cartels, were believed to be part of the protests that had turned violent in South Minneapolis, leaving hundreds of buildings damaged and burned in recent days. There were also local reports of armed white men roaming the area in out-of-state vehicles carrying symbols associated with a variety of online fringe groups with different agendas, including far-right militia, white supremacists, and anti-government firearm enthusiasts with pro-protester/anti-police politics.

If the threat of the coronavirus pandemic had forced Minneapolis residents to interact with other people almost exclusively through screens since mid-March, the threat of armed arsonists intent on starting a race war galvanized them into action IRL. They were worried that any organizing information they’d put on the internet could be seen—and therefore disrupted—by people who might mean them harm. So to air-gap these plans from would-be infiltrators, many organizing efforts went analogue, returning to tactics reminiscent of a pre-internet era. All day long, all across the city, citizens met in parks and in front of community centers to build phone trees (remember those?), form block peacekeeping patrols, and draw up plans to defend their homes and businesses from potential nighttime marauders. Read the whole thing.