Why We Wear Masks

Everything you ever wanted to know about the mask.

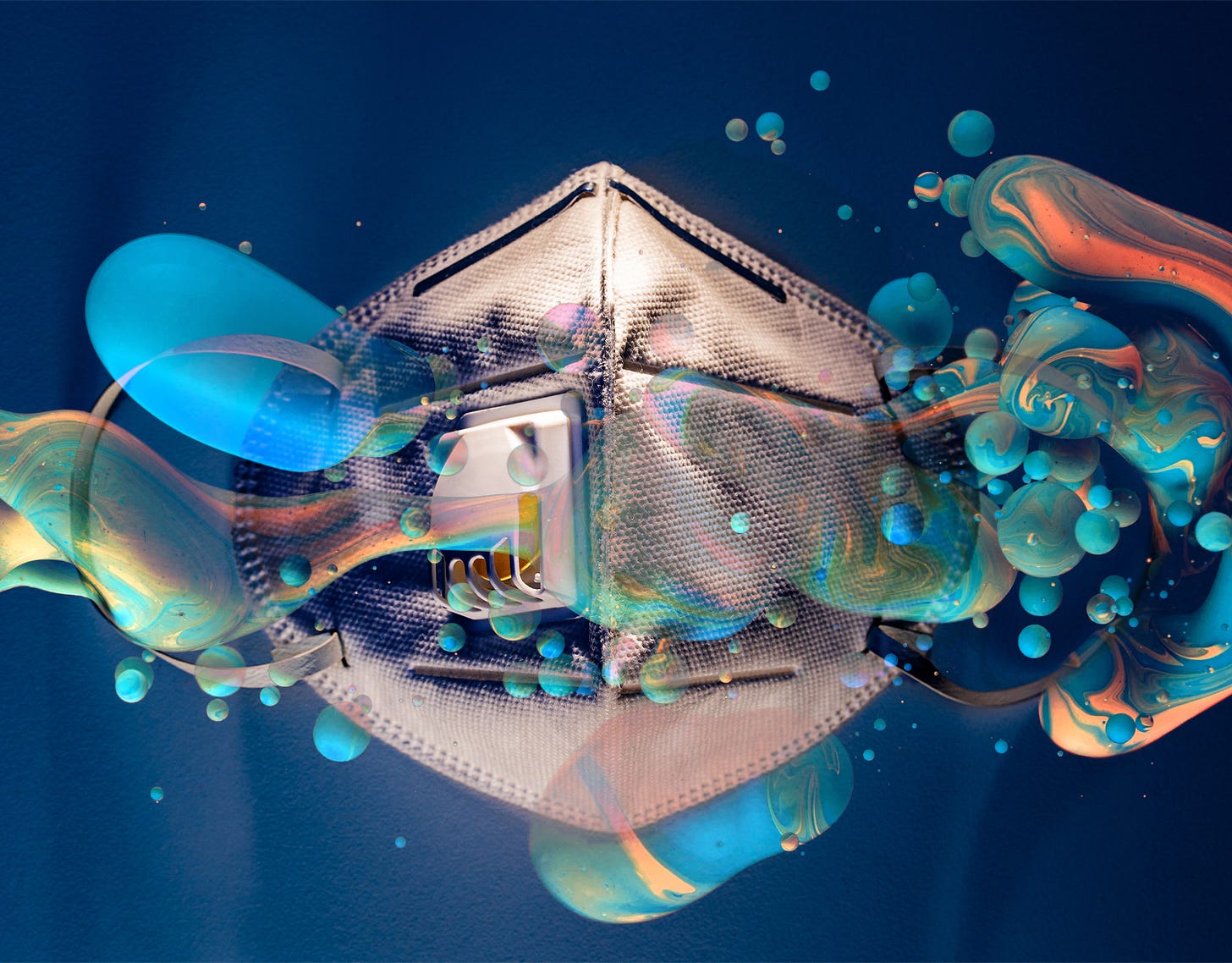

1. Masks and Fluid Dynamics

There is this thing going on where people seem to think that everything about public health during the pandemic is a binary choice.

(1) Either you lockdown everyone, indefinitely (2) Or you let everyone live their lives with no restrictions.

Or:

(1) Either everyone wears a mask for every minute of every day (2) Or no one should ever wear masks.

This is the wrong way of thinking about the crisis.

The goal of managing the spread of a virus through social distancing and lockdowns is to reduce the overall number of contacts the average person has in a day. We've talked about this before: You pick the low-hanging fruit first and then try to figure out what reasonable accommodations people will be willing to make and balance that against the marginal reductions in contacts you can gain from other restrictions.

We should be approaching mask usage the same way.

I'll talk about low-hanging mask fruit in a second, but first, a quick explanation on why masks are helpful.

You can't really understand masks unless you know a little bit about virology and a little bit about fluid dynamics.

On the virology front, you don't get sick from intaking a single virus particle. You need to take in an infectious dose sufficient to allow the bug to overwhelm your body's defenses and get a foothold within your system.

The size of the infectious dose varies from bug to bug. We don't yet know what it is for the novel coronavirus.

Which brings us to the viral load: That's the number of virus particles floating around in a person's system once they have the bug. For respiratory diseases in general, the higher your viral load is, the more virus particles you're going to shed when you cough, sneeze, or exhale.

So far, so good. Now the fluid dynamics.

Fluid dynamics is one of the most interesting sub-branches of physics. Here's my favorite problem:

You have a cup of green-colored water. You place it under a faucet and turn the tap on. As the new water fills the cup, the green water is displaced until there is no green water left and the cup is full of clear water. Fluid dynamics describes how this process works and what the various rates are.

Air is a fluid, too.

When you cough or sneeze or breathe, the virus particles aren't being expelled as pure particles—they're suspended in your fluids, which become aerosolized.

Aerosols are incredibly responsive to micro-climates. Here are two classic instances that deal with how aerosolized virus particles behave and how slight changes to the environment can alter their spread:

The spread of SARS on a plane is highly dependent on the direction of the ventilation system in the cabin. If you move the vents to the floor of the plane, then viral particle spreads become much more contained.

If you're sitting in a restaurant where another diner has COVID-19, whether or not you contract the virus has a great deal to do with where you are sitting in relation to the carrier and the local air flow. This case study is particularly illuminating. Look at these two diagrams of a restaurant where the coronavirus was passed on to some, but not all, diners:

Okay: This first diagram is the master layout of a restaurant in Guangzhou, China. You see tables represented by circles and squares and airflow represented by solid lines of the air coming out of an air conditioner and then dotted lines where the air redirects after bouncing off of a solid surface.

On January 24, the index case patient ate in this restaurant and following that event, 10 people came down with the virus.

This next chart is a detail of just the top half of the restaurant that shows the seating arrangements at that meal:

The red circle with yellow is the index patient. The other red circles are people who subsequently became infected. Notice how important the air flow is here: If you were in the corridor where the aerosolized particles were pinging back and forth from the spreader, there was a good chance of catching the infection.

But if you were at tables E or F, even if you were quite close to the carrier, no infections.

Which brings us to masks.

A mask isn't going to filter out virus particles. That's what respirators are for. The design purpose of the mask is to retard the spread of aerosolized droplets which carry virus particles. The mask either blocks these droplets entirely (if they are large) or slows their exit velocity (if they are small) so that gravity brings the droplets to ground at a shorter distance, reducing their physical spread.

Remember: The mask doesn't have to be an impermeable barrier in order to be effective because we're looking for the low-hanging fruit to mitigate spread.

There is some debate over how effective masks are in curbing the spread of aerosolized particles and that level of efficaciousness will depend on a bunch of factors: what the mask is constructed of, how it's worn, etc. But there is no serious debate that there is some effectiveness.

And whether the answer is that masks slow spread by 80 percent or 20 percent, we should be eager to bank that decline, because it's basically a freebie. In the grand scheme of economic expense and behavior modification, wearing a mask costs us next to nothing.

All of that said: Could we stop arguing about wearing masks while going for a run or taking a walk?

As U-Mass immunologist Erin Bromage makes pretty clear, these are very low-risk events. You are highly unlikely to get the coronavirus if you're out for a walk and a jogger who is carrying the disease runs past you without wearing a mask.

You don't need to wear a mask sitting in your car.

Wearing masks while shopping is more of an edge case because it's about stopping the spread of viral particles to hard surfaces which others will touch with their hands. And if you're standing 6 feet away from your neighbor chit-chatting for a minute, the world is not going to end if you're not wearing masks.

Because just like with reducing the overall number of contacts, what we're thinking about is reducing large-spread events.

The big-ticket items are places where you spend significant amounts of time face-to-face with multiple people in closed spaces: Riding mass transit, in the work place, in a school setting, at social gatherings. You should not be in a movie theater, for instance, without a mask. Or a bar. Or sitting in a doctor's office or any place that is indoors and has a waiting room.

These ought to be no-brainers for everyone while the outbreak is still operating at a large scale.

And even though our numbers are definitely improving, the virus is still operating at scale.

Being smart about masks is one of the ways we can keep pushing on the virus.

One last thing: Please don't email me saying "Actually, there's some evidence that masks don't help. Or that they're harmful." This is bs on the order of magnitude of anti-vaccine and flat-earth theories. There is not merit to both sides here.

Should you wear a cloth mask that has been marinating in bacteria for weeks on end? No. Wash them or disinfect them, often.

2. About that Death Star

Last week we talked a bit about my skepticism that Brad Parscale's Digital Dark Arts were all that effective.

Here's another data point: A fundraising email one reader got from the Trump Death Star. You tell me if this looks super-duper sophisticated to you:

You tell me:

Does this look like a super-sophisticated digital operation that's leveraging Big Data and machine learning and neural networks and AI and Eye of Newt in order to take dead aim at people's hearts?

Or does it look like an American version of the Nigerian email scheme?

3. Forgery

Another amazing piece from the Atlantic:

On the evening of February 1, 2012, more than 1,000 people crowded into an auditorium at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The event was a showdown between two scholars over an explosive question in biblical studies: Is the original text of the New Testament lost, or do today’s Bibles contain the actual words—the “autographs”—of Jesus’s earliest chroniclers?

On one side was Bart Ehrman, a UNC professor and atheist whose best-selling books argue that the oldest copies of Christian scripture are so inconsistent and incomplete—and so few in number—that the original words are beyond recovery. On the other was Daniel Wallace, a conservative scholar at Dallas Theological Seminary who believes that careful textual analysis can surface the New Testament’s divinely inspired first draft.They had debated twice before, but this time Wallace had a secret weapon: At the end of his opening statement, he announced that verses of the Gospel of Mark had just been discovered on a piece of papyrus from the first century.

As news went in the field of biblical studies, this was a bombshell. The papyrus would be the only known Christian manuscript from the century in which Jesus is said to have lived. Its verses, moreover, closely matched those in modern Bibles—evidence of the New Testament’s reliability and a rebuke to liberal scholars who saw the good book not as God-given but as the messy work of generations of human hands, prone to invention and revision, mischief and mistake.Wallace declined to name the expert who’d dated the papyrus to the first century—“I’ve been sworn to secrecy”—but assured the audience that his “reputation is unimpeachable. Many consider him to be the best papyrologist on the planet.” The fragment, Wallace added, would appear in an academic book the next year.