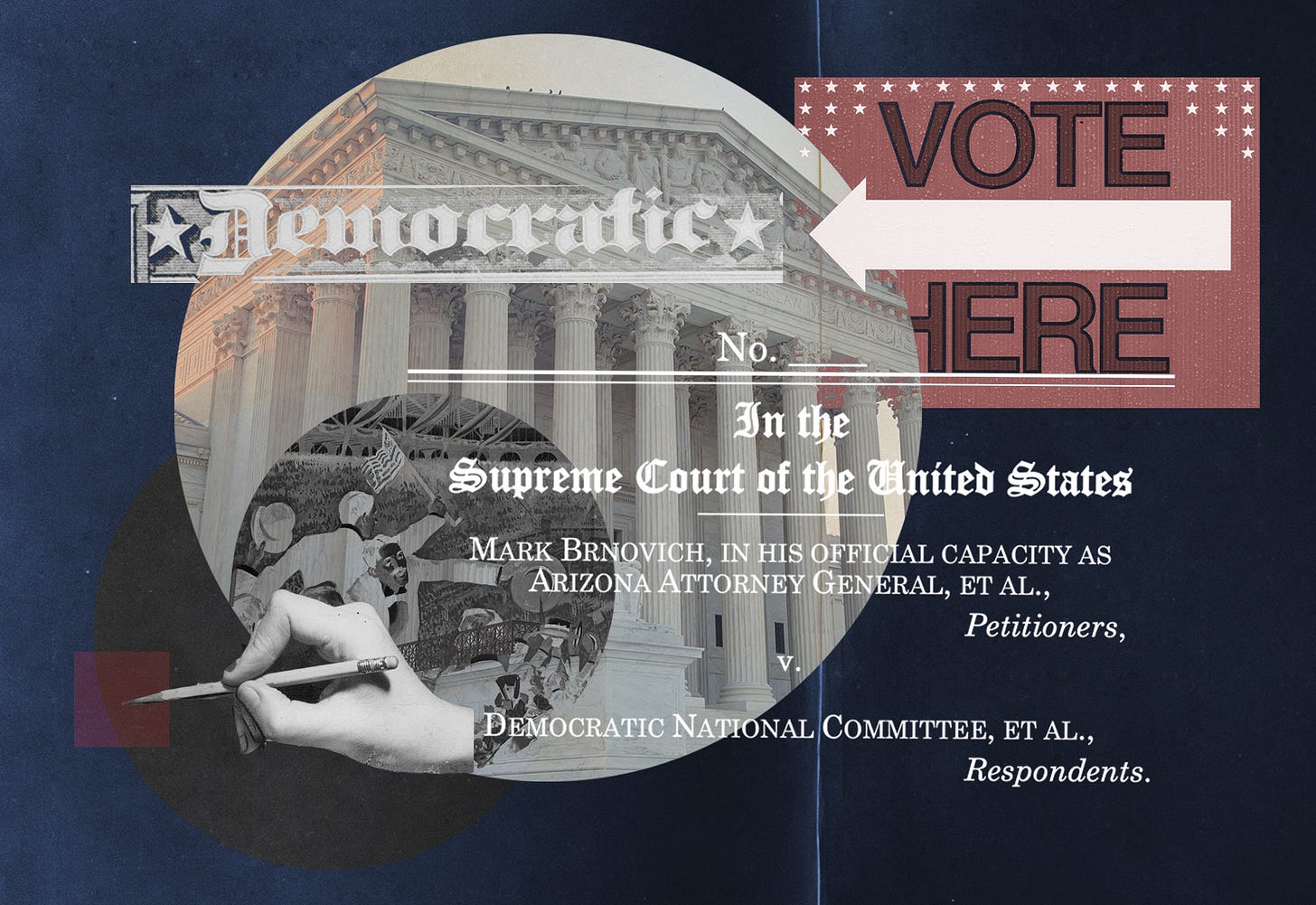

On Voting Rights, GOP Lawyers Say the Quiet Part Out Loud

Arguing before the Supreme Court, they admit their case isn’t about principle or election integrity—it’s just about winning.

In light of the ongoing assault on the legitimacy and integrity of U.S. elections, the timing of Tuesday’s Supreme Court oral arguments in Brnovich v. DNC is eerie. The consolidated case comes in the wake of the violence at the Capitol spurred by Donald Trump’s Big Lie about the 2020 election—and two days after the former president gave his first speech since leaving office, uttering falsehoods about American elections while his adoring audience chanted “You won!” It also comes as 43 state legislatures are considering 253 new voter suppression bills, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Something urgently needs to be done to save American democracy. Hopefully, the newly minted 6-3 conservative majority won’t make things worse.

The case challenges two provisions of Arizona law. One restricts the ability of third parties to collect ballots on behalf of other voters, an option that the plaintiffs argue is particularly important to Native American communities with limited access to U.S. postal services and transportation. The second is a law that tosses out votes simply because they were cast in the wrong precinct. The plaintiffs argue that this rule likewise harms communities of color, where poll locations are more often moved around or put in out-of-the-way places that are difficult to reach.

What makes the legal landscape different from just six months ago is that Republican politicians across the country aren’t even pretending anymore that voter fraud justifies these and other ballot restrictions. At oral argument in the Brnovich case, Justice Amy Coney Barrett aptly asked Michael Carvin, counsel for the Arizona GOP, what his client’s interest is “in keeping out-of-precinct voter disqualification rules on the books.” Carvin’s response was blunt: “Because it puts us at a competitive disadvantage relative to Democrats. Politics is a zero-sum game. It’s the difference between winning an election . . . and losing.”

This explanation has zero to do with election integrity or fraud. As Bill Kristol explained this week, we are in a fight for the survival of democracy itself. And the opponent of ‘We the People’ is the Republican party.

The Supreme Court is substantially to blame for this civic crisis. In 2013, it struck down a critical piece of the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965, which was widely celebrated across the political spectrum as one of the most successful pieces of civil rights legislation in the history of the United States. Section 5 of the act required states with histories of imposing arbitrary obstacles to voting—like literacy tests, poll taxes, and even correctly identifying the number of bubbles in a bar of soap—to run changes to its voter laws by the Department of Justice in a process called “preclearance.” Ironically, when Arizona tried in 2011 to get one of the provisions at issue in Brnovich through preclearance (what some pejoratively call “ballot harvesting”), it abandoned the effort.

Section 5 was renewed multiple times by huge margins in Congress. But in an opinion authored by Chief Justice John Roberts, a 5-4 majority of the Court in Shelby County v. Holder thumbed its nose at the legislature’s constitutional prerogative to pass laws on behalf of the people, sending Section 5 back to the congressional drawing board on the rationale that the data underlying the voter access law needed updating. Roberts also reasoned that the statute had done its job. Quoting a 1966 case that had challenged the Voting Rights Act, Roberts wrote that the “blight of racial discrimination in voting” that had once “infected the electoral process in parts of our country for nearly a century” was now fixed. Whew.

Writing in dissent, the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg acerbically retorted: “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.”

She was right. Voter suppression laws have since surged back.

Unable to use Section 5, voting rights organizations have turned to another provision of the Voting Rights Act to protect and preserve access to the ballot. Section 2 places the burden on voters—rather than invoking DOJ—to keep state legislatures honest. It allows voters to sue states and localities if they impose any “qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard, practice, or procedure . . . in a manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” Historically, Section 2 has primarily been used to challenge attempts to dilute the relative strength of votes cast by communities of color through maneuvers like redistricting. In Brnovich, the plaintiffs—who included the Democratic National Committee and individual voters—challenged the inability to cast a vote in the first place.

The legal issue in Brnovich boil downs to identifying what test should be applied to determine whether these kinds of laws violate Section 2. The statute itself doesn’t say. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit sided with the voters, applying a test that Carvin and Arizona Attorney General Mark Brnovich say is too lax. They argue that Section 2 can only be used in voter dilution cases in the first place—not to address restrictions on access to the polls, which was the primary job of Section 5. They would also impose a high bar for voter access cases that do get before a court, essentially seeking proof that state legislatures intentionally passed the law in order to discriminate against communities of color.

Although a conservative majority is unlikely to uphold the 9th Circuit and strike down these laws, counsel for the Republicans were clunky, at best. In sharp questioning, Carvin conceded that a law allowing people only to vote at country clubs would violate Section 2, going so far as to call it “laughable” that minorities would have the same “opportunity” to vote under that scenario. But “opportunity” sounds a lot like voter access, which Carvin’s team simultaneously claimed could not be remedied under Section 2. Moreover, the statute doesn’t use the word “opportunity,” and Carvin offered no meaningful test for judges to apply to distinguish between an opportunity and an “un-opportunity,” or whatever the opposite of opportunity might be.

At bottom, if a majority of the Supreme Court decides that this statutory ambiguity is not something that courts can or should fix under our system of separated powers, it might be right. That job is really for Congress.

This week, the House of Representatives is expected to vote on H.R. 1, the For the People Act, which would expand early and absentee voting, allow voters to register online or on election day, and require the use of paper ballots and auditing to protect the integrity of elections, among other measures. Also pending in Congress is H.R. 4, the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act, which would restore and update Section 5, among other important reforms. Anti-democracy Republicans in the Senate—many of whom are still peddling the Big Lie, despite an avalanche of contrary evidence and the bloody January 6 insurrection—are not going to vote for voters or these laws, and will likely use the filibuster to block it.

As I suggested last week, Democrats in the Senate thus have a choice: retain the filibuster or rescue democracy. Once again, the Supreme Court is not going to save us.