Our Abiding Quarrel with Russia

Russia has interfered in American elections before. It is again.

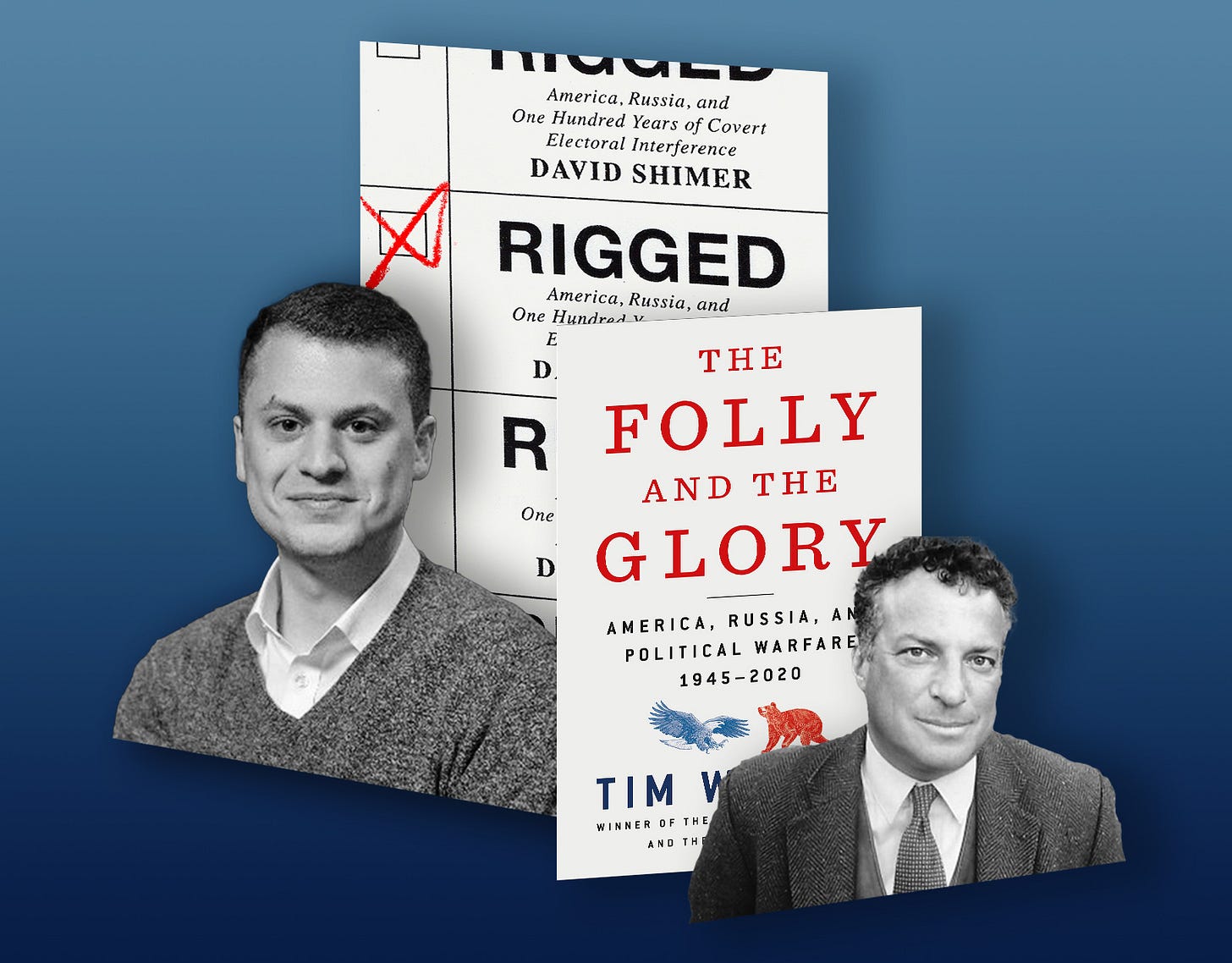

Rigged America, Russia, and One Hundred Years of Covert Electoral Interference by David Shimer Knopf, 367 pp., $29.95

The Folly and the Glory America, Russia, and Political Warfare, 1945-2020 by Tim Weiner Holt, 325 pp., $29.99

In publicly enlisting the aid of a hostile foreign power to interfere on his behalf in the last presidential election, Donald Trump seemed unaware that his vile gambit was superfluous. Vladimir Putin had already ordered a covert “influence operation” to manipulate the election for America’s highest political office. No one knew it yet, but the Kremlin’s campaign to sabotage the 2016 American election and help Trump become president would rank among the most successful clandestine operations in history. It was one factor among many that brought Trump to the White House, but in a historically close race, only the president’s purest sycophants—seldom in short supply—could write it off as inconsequential.

The fifth and final volume of the Senate Intelligence Committee report on Russia’s election interference, published in August and representing the culmination of three years of work, laid out an alarming catalogue of contacts between Trump’s circle of advisers and Russian government officials. This will come as a surprise to Trump’s defenders who insisted that the Mueller inquiry exonerated the president on charges of collusion. In fact, Mueller explicitly disclaimed that his team investigated collusion at all. (“We did not address ‘collusion,’ which is not a legal term,” Mueller said. “Rather, we focused on whether the evidence was sufficient to charge any member of the campaign with taking part in a criminal conspiracy.”)

In contrast to Mueller’s narrowly tailored criminal probe, the Senate Intelligence Committee report did investigate collusion. The most damning evidence of collusion has been in full view since Trump, on live-television, asked Russia to pilfer and publish Hillary Clinton’s emails. But the Senate report fills in some of the sordid details of the “aggressive, multi-faceted” Russian intervention to hack the email correspondence of senior Democratic figures and time their public release to maximize advantage for the Trump campaign. The committee did not establish a quid pro quo but the Trump associates who played the largest role in this scheme, campaign manager Paul Manafort and outside adviser Roger Stone, were convicted of lying to investigators. Only the most credulous partisans could believe that the serially shady conduct of the Trump clique earned any benefit of the doubt, or could accept the term “Russia hoax” as a taunt against Trump’s political opponents. In this, they demonstrated a supreme willingness to deceive themselves or others (or both).

Politics is not a nursery, and skullduggery is a routine feature of political life, but suborning the intervention of Russian intelligence in the American democratic process was an exceptionally brazen act. The party that benefited from this intervention has also stymied any efforts to protect the integrity of U.S. voting systems. And since there were no punitive measures taken in response to Russia’s interference—and thus no deterrence against future interference by Russia or other malicious actors—it will come as no surprise that, according to U.S. intelligence, Russia has undertaken to repeat this attack on America’s democratic process in the upcoming election.

Two new books document this squalid feature of the Trump era with a blend of first-rate reportage and scholarly precision. Rigged by David Shimer and The Folly and the Glory by Tim Weiner bring a sharp eye to the long history of electoral interference by America and Russia in the affairs of foreign nations, and each other’s. Both works shed light on the Russian effort to sow discord in Western democracies and to bring down the international system of liberal hegemony.

Rigged is a particularly engrossing history that opens in reverse chronological order, with Putin’s audacious—and, even in hindsight, astonishingly reckless—decision to launch a covert operation on behalf of the Trump candidacy. In the summer of 2016, President Obama faced a momentous choice. U.S. intelligence agencies had established that Russia was interfering in America’s upcoming election, and (thanks to a still highly classified source) confirmed that Putin personally directed the operation. The possibility of retaliating directly against the Kremlin—applying enhanced sanctions or releasing compromising information about Putin—possessed the virtue of deterring further meddling. But the risks of escalation were acute, as James Clapper, then the director of national intelligence, stressed. “What would the retaliation have been?”

As Shimer points out, the answer to that question was unknown. Russian intelligence had already stolen and released emails damaging to the Democratic party, in a transparent effort to cloud voters’ minds. But Russian hackers had also penetrated electoral systems and Washington feared that states and localities with unencrypted and insecure voter-registration databases were vulnerable to attack. If Putin was provoked to retaliate against even light American countermeasures, Russian operatives could have directly disrupted the voting process by deregistering voters or altering outcomes in swing counties. The entire election could’ve been thrown into chaos, even without an unscrupulous Republican candidate alleging that the election had been rigged. With Clinton favored to win the election, Obama exercised restraint.

This is not to say that Obama simply ignored the matter. Although the Obama administration initially underestimated the scope of Russian mischief that ultimately reached about 220 million Americans on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter, Shimer quotes an Obama official who claims that at a summit in China, Obama warned Putin: “You f— with us and we’ll take you down.” According to Avril Haines, the deputy national security advisor, efforts to manipulate state electoral systems constituted “a redline of sorts.” Russia’s operatives do seem to have feared they would have summoned a devastating response from Washington had they crossed it, and voting unfolded on election day without a hiccup.

Any relief felt by U.S. intelligence agents who were vigilantly monitoring for a Russian cyberattack was short-lived. The elaborate process undertaken by voters to decide how to cast their ballot had undoubtedly been manipulated by a sophisticated and often unsubtle Russian influence campaign. It may not have mattered that Russia didn’t prevent the actual operation of American democracy; a darker possibility remained: An outside force had conditioned the supreme choice Americans made at the ballot box, persuading them that their interests aligned with those of a hostile foreign power.

In the waning days of his presidency, Obama ordered a bevy of economic and diplomatic reprisals against the Russian state, expelling diplomats and imposing sections. But the costs of these measures were infinitesimal compared to the windfall that the Kremlin reaped from helping to elect Trump to America’s highest office. After the fact, senior Obama officials expressed regret at the diffidence shown in real time during Russia’s great act of aggression against the United States. Obama’s reticence was a classic case of well-intentioned folly that so often bedeviled U.S. foreign and defense policy during his term. Instead of defending U.S. interests with unflinching resolve and leading the Western democracies to deter Putin’s malevolence, sins of commission were the only ones that he sought to avoid. Inevitably, sins of omission proliferated on his watch—to the detriment of U.S. interests.

Complementing Shimer’s book, Tim Weiner’s The Folly and the Glory reveals the modern scope of Russia’s information warfare, and how it both recycles past tactics as well as innovating new ones.

During the Cold War, the KGB had a special department—“Service A”—responsible for “active measures” (aktivnyye meropriatia) designed to fracture and enfeeble the West. Weiner sheds light on how subversion and campaigns of disinformation featured prominently in the Soviet Union’s intelligence services, thanks to Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB in the 1970s and one of Putin’s heroes. The author quotes a retired KGB major general as claiming that subversion, not espionage, was “the heart and soul of Soviet intelligence.”

By the 1980s, the CIA estimated the active measures department had 15,000 officers and an annual budget of $4 billion. But the program went as far back as World War II. In 1946, in his famous long telegram, George Kennan argued that the Soviet Union would not attack America militarily but that it would go out of its way “to undermine general political and strategic potential of major Western powers . . . to disrupt national self confidence, . . . to increase social and industrial unrest, to stimulate all forms of disunity. . . . Where suspicions exist, they will be fanned; where not, ignited.”

When the Soviet Union collapsed, this department was refashioned, but not dismantled. The active measures undertaken by Putin’s security services against liberal ideology have harnessed modern technology to create more disruption than was thinkable during the Cold War. The template of Cold War elections that the Soviets and Americans sought to influence had a very different cast. To take one example: Fearful that the Communists would win enough votes to dominate the Italian parliament, the United States intervened to help the anti-Communist Christian Democrats to a landslide victory in that country’s 1948 election. Shimer recounts the ingenious methods by which that influence was conveyed: Italian-Americans were encouraged en masse to write letters to their Old World relatives, and an estimated 10 million messages were dispatched warning of the dangers of communism.

The Kremlin no longer restricts itself to promoting crude political slogans to influence outcomes in American elections—in the early 1980s it tried to stop Reagan’s re-election by advertising “Reagan Means War!” Although Russian intelligence did circulate rumors that a vote for Hillary Clinton would risk a thermonuclear exchange with the Russian Federation, Putin had also refined Andropov’s department into a more complex and insidious machine of political warfare.

Weiner covers this evolution of Russian intelligence deftly. The Internet Research Agency, financed by a wealthy Putin confidant and working at the direction of the Kremlin, assembled an army of English-speaking and internet-savvy trolls in St. Petersburg to deepen and inflame American political divisions online. The IRA’s campaign reached millions of voters. It connected with at least 126 million Americans on Facebook, 20 million on Instagram, and more than 1 million on Twitter. This invisible campaign generated innumerable social media interactions, some of which were directly recirculated by Trump and his surrogates. What’s more, a Russian military intelligence front started deploying stolen Democratic National Committee documents with maximum effect into the political arena. Moscow had conscripted ostensible opponents of government secrecy such as Wikileaks as instruments of Russian intelligence to circulate these ill-gotten goods.

The potential danger of direct electoral interference should not blind us to the realized version of another danger. The mechanism of voting need not be changed or subverted when minds have been changed or sullied. In an age of social unrest, the American mind is as deeply impressionable as ever, and the concerted efforts of a hostile foreign state to derange that mind ought to stir every American to vigilance against Russian-engineered “fake news.”

The main stumbling block toward this broad public understanding lies with the cohort of pro-Trump Republicans, who have always been skeptical of the evidence of Russian meddling. From their vantage point, Trump’s hawkishness toward Russia invites doubt about claims that he enjoys Putin’s support. This argument has been advanced in spite of the president’s unrelenting praise for Putin and suggestion that NATO is “obsolete.” This argument has somehow even survived the president’s efforts to force the Ukrainian government to announce an investigation into Joe Biden by hindering the delivery of lethal aid to Ukraine—aid that Ukraine needs to defend its sovereign territory from Russian aggression.

It is hardly to Trump’s credit, but it’s important to recognize that Republican criticism of the Obama administration’s feeble posture toward Russia had a sound basis in fact. In 2016, Hillary Clinton, although certainly no dove, was prone to indulge the Democratic habit of signaling weakness to the nation’s enemies. It was Clinton, after all, who as Obama’s secretary of state launched the ill-fated “Russian reset” on the notion that tensions with the Kremlin lay more with past Republican intransigence than Putin’s own determined calculations of the Russian national interest. This dubious assumption bred an accommodationist policy that undoubtedly impaired U.S. interests. But it is precisely this fact that makes even more suspicious Putin’s strong preference for her opponent.

During the 1970s, in another era of American confusion and retreat, Ronald Reagan sought to re-engage the United States in a decisive ideological struggle with the Soviet Union. This return to the robust antitotalitarianism of the early Cold War earned Reagan scorn from the reigning progressive consensus, but also from the illiberal conservatives in his own party. In office, Reagan drove both progressives and self-described realists to distraction by baldly declaring the Soviet Union an “evil empire” and waging a fierce and unrelenting political struggle against Soviet communism.

In a remarkable volte face, a quarter-century after the free world’s triumph in the Cold War, a Republican standard-bearer had become Russia’s preferred candidate. In his first term, Trump has discredited American institutions, divided the social order, and diminished the nation that has been indispensable to the liberal order.

Little wonder that at this hour Russian intelligence services are working tirelessly to perpetuate the Trump presidency. Americans preparing to vote the same way in November should ask themselves what could possibly justify contributing to another election result that would be celebrated in the Kremlin with champagne.