60 Years Ago, Courage Confronted Racism at the Democratic Convention

My grandmother and the fight over the 1964 Mississippi delegation.

WHEN VICE PRESIDENT KAMALA HARRIS takes the stage in Chicago on Thursday night at the Democratic National Convention to accept her party’s nomination for president of the United States, I will raise a glass to my grandmother from Newton, Mississippi and remember again the year she stood up to powerful, undemocratic white men.

Thelma McMullan arrived as an alternate delegate at the 1964 Democratic convention in Atlantic City. She was a 57-year-old white woman from Mississippi. Her husband, Milton, 60 and white, was an official delegate of the Mississippi Democratic Party.

President Lyndon B. Johnson was the nominee. Thelma supported Johnson. Milton did not. He and other white Mississippi delegates passed the following resolution before the convention: “We oppose, condemn and deplore [President Johnson’s] Civil Rights Act of 1964. . . . We believe in separation of the races in all phases of our society.”

That summer arrived following a bleak season of political violence in our country. John F. Kennedy had been shot and killed the previous November. Medgar Evers had been shot and killed months before Kennedy. And then, in the immediate runup to the convention, there were the 1964 Freedom Summer murders. Civil rights workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were killed in Neshoba County for helping black citizens register to vote. Members of the KKK and local police had murdered them.

The new Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) was at the convention, too. Cofounded by Fannie Lou Hamer, who that summer famously said, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired,” the upstart party was made up of elected white and black delegates. They were there to challenge and protest the Mississippi Democratic Party’s all-white delegation, which had ignored federal election law by excluding black Mississippians in their selection process. Most of these regular delegates had no intention of supporting Johnson in the November election. They planned to switch to the Republican presidential candidate, Barry Goldwater, because he opposed the Civil Rights Act.

At the opening of the convention, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party made its case to the credentials committee that their alternate slate of 68 delegates should be seated.

The proceedings were televised.

“The seating of the delegation from the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party has political and moral significance far beyond the borders of Mississippi, or the halls of this convention,” Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. said in support of the MFDP delegates.

Then Fannie Lou Hamer gave her own hair-raising account in exacting detail of how she and other black Mississippians seeking the right to vote were extorted, threatened, harassed, shot at, beaten, jailed, then beaten and tortured again in jail.

Hamer’s speech electrified the members of the credentials committee, who were ultimately responsible for seating Mississippi’s delegates. Unwilling to seat the delegation outright, they offered MFDP delegates two seats and a handful of other compromises. The MFDP rejected the offer and continued protesting by singing hymns in the gallery.

While trying to find a way forward that would allow the MFDP on the floor in some capacity without completely alienating other delegations from across the South, the credentials committee made a series of political maneuvers. One was to require Mississippi delegates to take an oath swearing they would support the party’s nominee for president. Another was to commit the Democratic party to adopt new rules that would require future state delegations to open their selection process to black as well as white voters.

Mississippi’s regular delegates gathered in a room at Boardwalk Hall to take the loyalty oath. My grandmother stood up to sign.

“Sit down, Thelma,” Milton said, refusing himself to sign the oath.

“Don’t you tell me what to do, Milton,” she said.

In the end, nearly all of the sixty-eight Mississippi delegates refused to sign the oath. My grandmother Thelma was one of four or five who signed, although press coverage at the time mentioned only three men who did.

Later, she received a telegram from Milton’s brother with a warning to look out for the Ku Klux Klan. They were coming for her.

She told me she was never afraid.

THAT FALL, AFTER THE CONVENTION, Lady Bird Johnson invited Thelma to Washington to join her on a campaign train ride down the eastern portion of the country.

My grandmother recalled that time the rest of her life. First Lady Johnson shared her ideas of planting trees and wildflowers near highways built during the Eisenhower administration, which later became the Highway Beautification Act of 1965, also known as “Lady Bird’s Bill.”

Thelma and the few other regular Democratic delegates who did not join the walkout at the 1964 convention faced threats and harassment from the KKK and segregationists. Some of them moved away. Thelma continued living in Mississippi until the day she died.

By signing that oath, Thelma became a hero within the Democratic party. That year’s convention was a turning point. Although the MFDP delegates ultimately rejected the party’s compromises and were not seated, their actions significantly influenced the Democrats’ future direction. After 1964, it was required that all delegations be open to both black and white representatives, and in 1968, a group of MFDP alumni—then calling themselves the “Loyal Democrats of Mississippi”—would be seated as the state’s official delegation at that year’s convention.

Legendary journalist Bill Minor, who wrote a remembrance of Thelma following her death in December 1998, told an interviewer in 2012 that “Even today she and her actions would be courageous. In a lot of ways things haven’t changed all that much.”

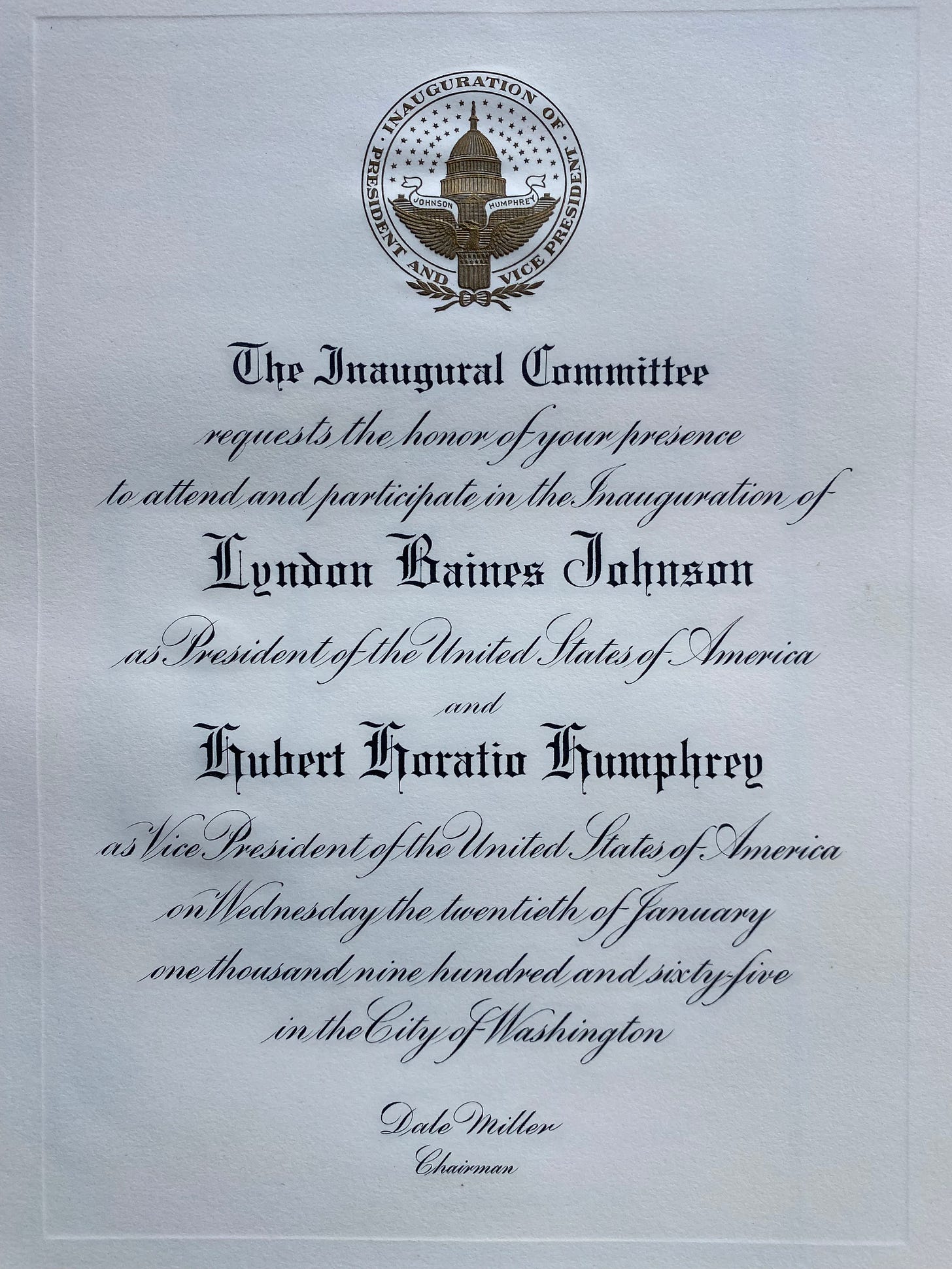

I still have the magnolia platter my grandmother used to serve pimento cheese sandwiches. I have her book of poems, her recipe for pear preserves, the luggage she gave me when I graduated from high school, and her invitation to President Johnson’s inauguration in January 1965:

As momentum continues to build for Vice President Harris to become our first black woman president, I can’t help but think how thrilled my grandmother would be.

Thelma understood the courage it sometimes takes to fight for democracy. Now it’s up to us.