1. A Death in Afghanistan

My friend Will Selber, a Foreign Area Officer, recently left Afghanistan. Over the weekend he wrote an obituary for a man he worked with over there, Sohrab Azimi, who was killed. Will has kindly let me share his note with you:

Lieutenant Colonel Sohrab Azimi, a highly decorated Afghan National Army Special Operations Corps (ANASOC) commander, was killed in action, along with members of his Joint Special Operations Coordination Center (JSOCC) targeting team, on 16 June 2021 in Dawlat Abad District, Fayrab Province, Afghanistan.

LTC Azimi was a 2019 graduate of the United States Army Command and General Staff College, as well as its Captain's Career Course. He was also a plank holder for the United States Defense Attaché Office Kabul's Strength and Wisdom Network (SWiN). SWiN helps Afghan officers, who graduated from American military universities, further their career development by coordinating lectures with some of the United States’ foremost foreign policy experts.

The son of General Zahir Azimi, a former Ministry of Defense (MoD) Spokesman, LTC Azimi dreamed of becoming the Chief of General Staff (CoGS), which is similar to the Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff. However, instead of trading in on his father's name and reputation, LTC Azimi chose to join some of ANASOC's most elite units, placing himself in harm's way repeatedly. His units were often responsible for accomplishing some of the most daring and complicated missions in Afghanistan.

LTC Azimi had a warm personality and was quick to crack a joke, especially at the expense of Afghan Air Force and United States Air Force officers (including myself), who he affectionately referred to as “Chair Force” officers. I did not have the honor to serve in the field with Sohrab. Regrettably, I’ve grown too long in the tooth for that. However, he had a sterling reputation as one of Afghanistan's most promising officers. I will remember his quick wit, his civil-war era beard, and his ability to tell off-color jokes in multiple languages.

According to an MoD contact, since the US-Taliban agreement was signed on 29 February 2020, over 6,000 Afghan National Defense and Security Force (ANDSF) have been killed fighting a ruthless enemy who is still allied with Al Qaeda.

Our prayers are with LTC Azimi’s family and his comrades fighting America's enemies.

A great many Afghans put themselves on the line over the last 20 years to work with, support, and aid American troops. Some, like LTC Azimi, did so as soldiers. Some did so as interpreters.

These men and women have been abandoned by Biden’s withdrawal. It is both tragic and dishonorable.

There are roughly 18,000 Afghans on the waiting list for special visas—these are men and women who helped America and will certainly be targeted by the Taliban as a result. Every last one of them ought to be brought to America before the September 11 pullout.

There is not a SIV program for Afghan soldiers, even for the thousands of female soldiers who we encouraged to join despite the threats to their lives. So bringing out our interpreters won’t be enough.

But it would be a start.

2. Tallahassee Help Wanted: Food Tester

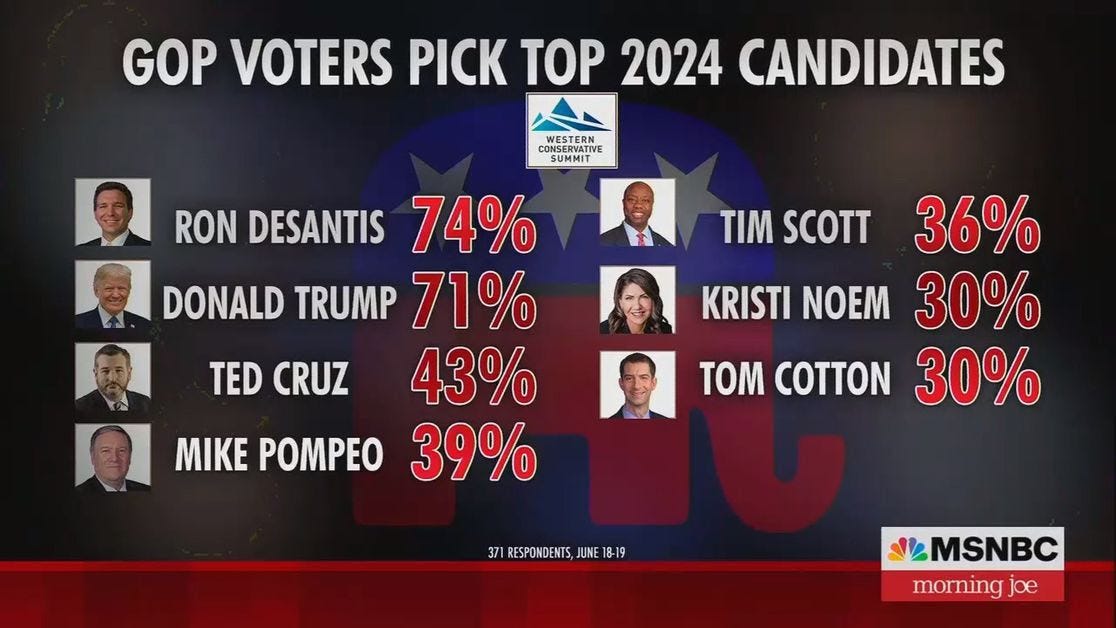

If Ron DeSantis didn’t need protection before, he sure needs it now:

I remain amazed at the left’s response to DeSantis’s rise. They seem to be panicking and lashing out instead of celebrating it.

Here’s a secret: If you want to destroy the presidential hopes of Ron DeSantis you don’t do it by attacking him.

You do it by celebrating him as The Smart Version of Trump.

Ron DeSantis could get caught with a dead hooker or a live boy and it wouldn’t matter one bit to Republican voters.

But if Molly Ball does a favorable profile of DeSantis and puts him on the cover of Time magazine with the headline “The Smart Version of Trump,” MAGA will turn on him in a Miami minute.

3. Aerosols

One of the maddening parts of early COVID was watching the medical establishment parse the technical meaning of “airborne” when it was clear that COVID was being transmitted by aerosolization. This Wired piece tells the story of how that happened, and why:

Marr is an aerosol scientist at Virginia Tech and one of the few in the world who also studies infectious diseases. To her, the new coronavirus looked as if it could hang in the air, infecting anyone who breathed in enough of it. For people indoors, that posed a considerable risk. But the WHO didn’t seem to have caught on. Just days before, the organization had tweeted “FACT: #COVID19 is NOT airborne.” That’s why Marr was skipping her usual morning workout to join 35 other aerosol scientists. They were trying to warn the WHO it was making a big mistake. . . .

Over Zoom, they laid out the case. They ticked through a growing list of superspreading events in restaurants, call centers, cruise ships, and a choir rehearsal, instances where people got sick even when they were across the room from a contagious person. The incidents contradicted the WHO’s main safety guidelines of keeping 3 to 6 feet of distance between people and frequent handwashing. If SARS-CoV-2 traveled only in large droplets that immediately fell to the ground, as the WHO was saying, then wouldn’t the distancing and the handwashing have prevented such outbreaks? Infectious air was the more likely culprit, they argued. But the WHO’s experts appeared to be unmoved.

On the video call, tensions rose. At one point, Lidia Morawska, a revered atmospheric physicist who had arranged the meeting, tried to explain how far infectious particles of different sizes could potentially travel. One of the WHO experts abruptly cut her off, telling her she was wrong, Marr recalls. His rudeness shocked her. “You just don’t argue with Lidia about physics,” she says.

Morawska had spent more than two decades advising a different branch of the WHO on the impacts of air pollution. When it came to flecks of soot and ash belched out by smokestacks and tailpipes, the organization readily accepted the physics she was describing—that particles of many sizes can hang aloft, travel far, and be inhaled. Now, though, the WHO’s advisers seemed to be saying those same laws didn’t apply to virus-laced respiratory particles. To them, the word airborne only applied to particles smaller than 5 microns.