A Great Historian’s Inner History

Peter Brown’s remarkable memoir attests to the extraordinary powers of imagination he used to reconceive the study of late antiquity.

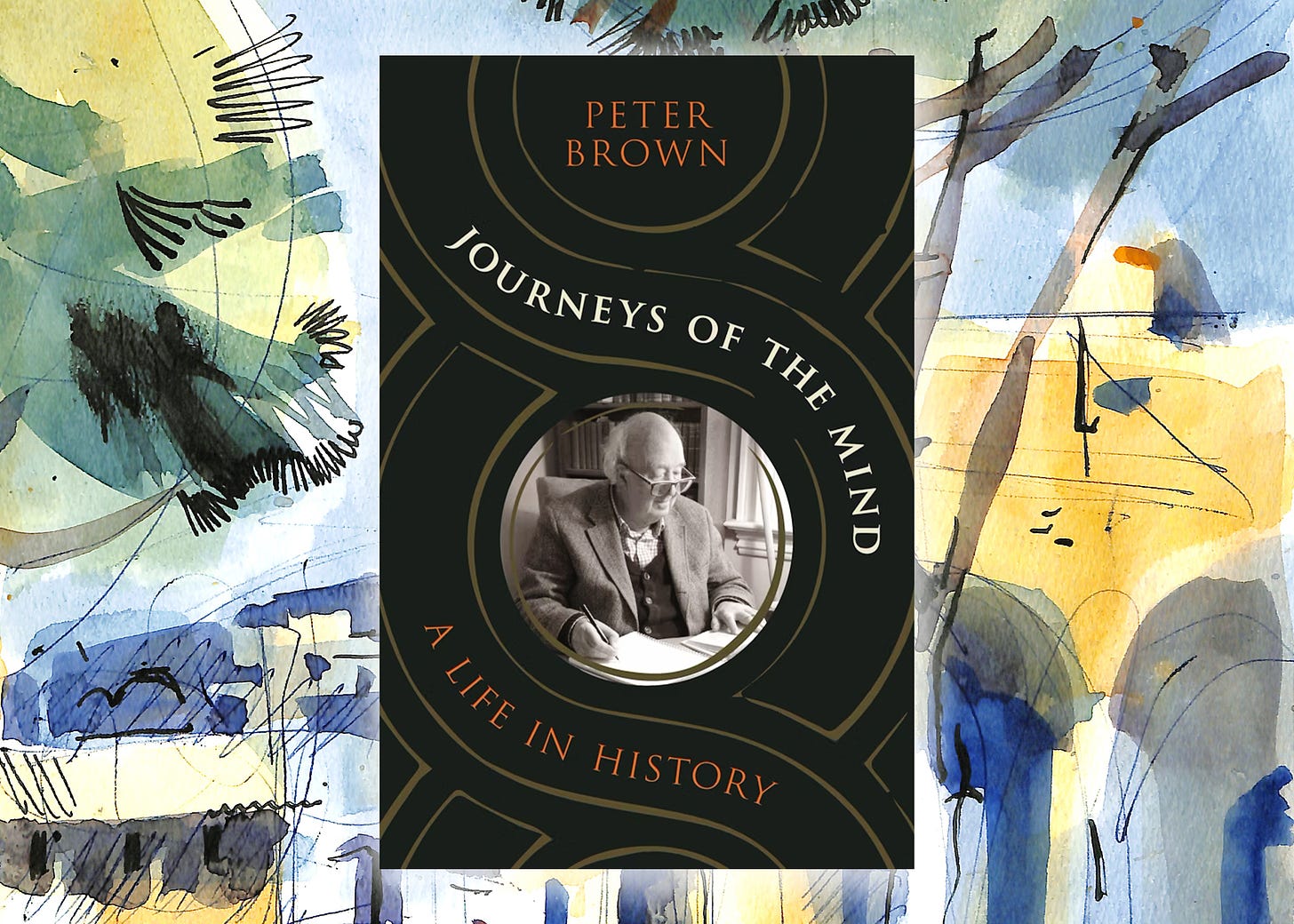

Journeys of the Mind

A Life in History

by Peter Brown

Princeton University Press, 736 pp., $45

PETER BROWN HAS THE POSSIBLY UNIQUE DISTINCTION of being read on a regular basis in two of the most ideologically dissimilar institutions in the United States: the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and the New York Review of Books. He is commonly assigned at the former, and he is a longtime contributor to the latter. It is a testament to Brown’s generosity of spirit and expansiveness of mind that he finds welcome readers at both places.

By any account, Peter Brown has had an extraordinary career. He wrote what is almost certainly the most widely read biography of St. Augustine in the English language. He has hobnobbed with the world’s foremost intellectuals in a variety of disciplines, not only benefiting from their influence but influencing them in return. And he is almost single-handedly responsible for establishing late antiquity as a legitimate field of historical study, reinterpreting it not as a moribund period in a decaying Roman Empire but as a time of great cultural ferment and creativity. Indeed, it is largely because of Peter Brown that we readily identify late antiquity as a historical period at all.

None of these achievements, however, quite explains what makes Brown’s new intellectual memoir, Journeys of the Mind: A Life in History, so compulsively entertaining and readable. The achievements lend interest, to be sure, but not fascination, and that latter quality is what has generated so much enthusiasm for this book among critics, editors, writers, and Brown’s fellow academic humanists since its publication in June. But before I hazard an explanation for what exactly it is that made me and so many others gobble up Brown’s book by the hundreds of pages, it is necessary first to fill in a few more details.

Brown’s book chronicles his birth to a middle-class Protestant family in Ireland just before World War II and continues up to his mother’s death in 1987, by which time he has become a professor of history at Princeton with a global reputation. In the intervening years, he rehabilitated St. Augustine, upended Gibbon’s grand narrative of ancient Rome’s decline and fall, tooled around the Middle East in Land Rovers and helicopters, and reconceptualized subjects like Syrian holy men and the cult of the saints that had been dismissed as superstitious Dark Age ephemera by previous generations of post-Enlightenment party-pooping historians. At the point on Brown’s personal timeline that Journeys of the Mind stops, the author has just finished writing The Body and Society, his groundbreaking book on sexual renunciation in late antiquity.

Along the way are many delicious and detailed recollections: his childhood visits to Sudan, where his father worked as a railway engineer; his travels through pre-revolutionary Iran while conducting research on the Sasanian Empire; his encounters with brilliant, famous, and eccentric personalities like C.S. Lewis and Mary Douglas, Michel Foucault and Pierre Hadot; and his dishy, behind-the-scenes accounts of writing his many influential books and essays. In these last sections, Brown never contents himself with summing up a piece of writing or a stage of his career. He instead provides a miniature education, setting off bright little bursts of scholarship on the page. He also provides honest reevaluations of his own works, freely admitting where he was wrong, overstated, unfair—or dead right. This is something he has been doing for years, as new editions of his earlier works attest. After becoming standard texts in the field of late antiquity, a number of Brown’s early-career studies have been republished with substantial forewords and afterwords, some of them pushing a hundred pages. For example, after I finished reading his biography of Augustine for the first time—the book was Brown’s first, originally published in 1967—I had several criticisms. But I was reading the new edition, published in 2000, and in his seventy-nine-page epilogue, he addressed every single one of them with humility and good faith.

BUT AS COMPELLING AS BROWN’S VAUNTED CAREER IS, with its tony scholarly halls, its archaeological digs, its ancient Middle Eastern monuments, its discipline-transforming works of scholarship, and its beautiful evocations of the intellectual life, something more is at work in this book. There is something irreducible and unique in these pages, something distinctly . . . Peter Brown–ish.

That magical, deeply personal quality is one I have come to most closely associate with his sense of imagination. It is the unifying principle of his body of work, and it explains the moreness of his thinking, the element that lifts his writing beyond the bounds of academia and into the broader, more capacious world of public intellectual life. Because Brown relentlessly imagines his way into the past—into the unfamiliar, the alien, the misunderstood. He doesn’t reconstruct it or dissect it. He first sees it and hears it; he puts himself within it. He imagines it so that we might imagine it with him, and so imagine the world as the ancients imagined it.

Consider how he describes his first visit to the catacombs in Rome:

In the Museo delle Terme and in the Vatican Museum, I lingered for hours in front of the great sarcophagi of the third century AD. I would stare at those tranquil, still classical faces—those grave public servants; those solemn children guarded by austere philosophers; those wives posed book in hand, as Muses to their husbands. Could they have dreamed of the future that lay in store for them within only a few generations? Could they have dreamed of Constantine? Or were they already, beneath their classical robes, dreaming of new worlds, but in a manner that escapes us?

This vivid presentation of imaginative detail is not the result of a submerged, unconscious impulse but a methodological first principle for Brown. In a lecture he delivered at Royal Holloway College in 1977 titled “Learning and Imagination,” Brown briefly steps back to reflect on the discipline of history. It is essential to the historian’s task, he says, to cultivate an “imaginative curiosity about the past” and to “imagine with greater precision what it is like to be human in situations very different from our own.” As a sort of extended case study, he argues that our imagination of the cult of the saints in late antiquity is inhibited by a prior imaginative model, that of David Hume, which dismisses “popular religion” as superstitious and irrational. But to dismiss popular religion because it “exhibits modes of thinking that are unintelligible,” Brown says, is “to give up prematurely.” Rather, “the historian has to strain the ear to catch an alien music in what had first sounded a cacophony.”

Brown’s imagination was conditioned by his upbringing as “a religious minority”: a Protestant family in a Catholic country. This sense of native displacement gives him empathy for those who believe differently and who are consequently misconstrued and mischaracterized, and it imbues his work with an impatience for settled opinion and smug dismissal.

It is deeply, ruefully human to treat with hostility parts of the past that do not line up with our beliefs and assumptions about the world—the way it works and our place in it. These assumptions can constrain one’s imagination by disciplining it to remain within safe boundaries. In keeping with his critique of Hume, however, Brown treats these encounters with an alien past, so often experienced as occasions for anxiety and ideological friction, in a positive way, recasting them as opportunities for curiosity and understanding to bloom.

He is eager to make the unfamiliar intelligible. This is true whether he’s investigating the supposed theological intransigence of St. Augustine or the ostensibly bizarre behavior of Syrian stylites or the seemingly incredulous veneration of the dead by St. Gregory of Tours or the allegedly world-denying sexual renunciation of the Desert Fathers. Supposed, ostensibly, seemingly, allegedly—Peter Brown’s work has made the inclusion of all these qualifying words in the previous sentence more defensible. On one level, this is because he has mounted successful challenges to the earlier consensus position on each subject, opening it up to new debates; on a deeper level, he has made these redescriptions possible through his willingness to see in these distant chronological strangers the “human position,” as Auden puts it. He sees them, in other words, as human figures in a human landscape. He brings them closer to us, making stereotypes about them harder to maintain.

This generosity of outlook extends not only to the disparate voices of history but also to his contemporaries and colleagues, particularly cultural anthropologists like E.E. Evans-Pritchard and Mary Douglas. They showed Brown how to see in cultures distant from our own, whether two thousand miles away or two thousand years ago or both, not superstition or megalomania but intricate and humane social functions deeply integrated with religious belief and practice. His gratitude for their example repeatedly bubbles to the surface.

BROWN’S WRITING ITSELF IS ALIVE with his imagination. He is ever alert for the arresting image, the elegant phrase, the carefully chosen metaphor that captures the spirit of his subject. It was reading a collection of his essays, Society and the Holy in Late Antiquity, many years ago that first gave me a sense of the way you could carefully choose a metaphor and concatenate it throughout a sentence. Writing about how the rise of Islam disrupted Roman Mediterranean culture in the eighth century, he says,

The Arab war fleets had twisted a tourniquet around the artery by which the warm blood of ancient civilization in its last Romano-Byzantine form had continued to pulse into western Europe.

Brown’s writing is filled with these kinds of activated metaphors. Overly dismissive modernist interpreters of St. Gregory of Tours, for instance, were “inclined to join, as in a maximum and minimum of thermometer, the low ebb of Gregory’s Latinity with the high tide of his credulity.” And for those in late antiquity who experienced the presence of the holy dead at their tombs, “it was as if the energy of Paradise flowed back into their dead bodies, so that their tombs ‘blazed’ like crackling lightning with miracles of healing and similar deeds of power.” Even the sentence I quoted a few paragraphs above, “the historian has to strain the ear to catch an alien music in what had first sounded a cacophony,” exhibits this intentional stringing together of a single set of images.

These are not decorative embellishments; once again, we see the outworking of a fundamental premise of Brown’s method. A metaphor defamiliarizes something in order to bring fresh, renewed meaning to the reader from an unexpected direction. This process of recognition through defamiliarization occurs at more than just the sentence level: It is intrinsic to Brown’s entire sense of history. Understanding how different the experience of the world was for those in the past is crucial to sensing our common humanity with them. At the heart of his biography of Augustine, Brown says in Journeys of the Mind, was “the deliberate use of analogies drawn from many aspects of the modern world.” Figures from the past, he says, are “not only fifteen hundred years away” but are “in some way . . . also still with us.” Augustine’s thought, for instance, is in some ways like Freud’s, but drawing this similarity through analogy both respects the fifteen-hundred-year interval between the two men and acknowledges their essential relatedness in the stream of Western thought.

This understanding of metaphor as central to history makes his writing both accessible and beautiful. Brown says often that he pitched the tone and style of his writing at “my aunts,” exemplars to him of the educated but non-expert reader. He “was determined,” he says, “that Augustine of Hippo would be a book of literary value: that the very rhythm of its sentences, when read aloud should maintain a momentum that carried the reader from one end of Augustine’s life to the other.” He succeeded.

But Brown’s high and highly controlled style lead to a curious lacuna in Journeys of the Mind. While he is generous with his rhetorical firecracker flourishes in passages devoted to history, he tends to hold them back from the chapters devoted to his family of origin. That’s not to say these latter chapters are dull, but that I often found myself wondering how these two poles of the book—intellectual history and personal memoir—are related. The quiet seems to deepen around the subject of religion, not as a matter of historical fact but of private conviction. Brown’s mother, he says, was a believer but did not consider herself a “religious” person. (Despite being painfully lonely late in life, she abhorred visits from her local priest.) Her son seems to have inherited a similar reticence. When it comes to his personal life, particularly after childhood, Brown seems to become more withholding.

For instance, I was surprised to find Brown in 1954, during his days as an Oxford student, coming forward at a London Billy Graham crusade “to receive the forgiveness of God.” This experience, interestingly, did not ignite revivalistic fervor but “jolted free” his imagination to embrace “the strangeness of history,” which, for him, was where his “sense of mystery lay.” The experience turned out not to be the sunrise of new religious devotion but the sunset of his childhood faith. He would not attend church again for twenty years. The thing I found most curious about this subtle and significant episode was that, after setting up this encompassing frame for his own religious convictions, Brown gives his return to faith a fairly summary treatment: He writes only that, impressed by the religious devotion he witnessed in Iran, he resumed attending church.

It’s not that I’m all that interested in gossip from Peter Brown’s personal life. But I am interested in the ways a set of personal beliefs informs one’s intellectual project. And in Brown’s case it seems like they do in more ways than he is willing to investigate. I was eager to read Journeys of the Mind, in part, to observe the consequences of Brown’s inner life for his scholarship. Who is the man in the tall tower? What manner of interiority bore the fruit of his subtle, sweeping reinterpretations of the Christian past? I didn’t come away from Brown’s book with a very clear answer. Because when he’s reinterpreting, say, the cult of the saints, emphasizing in Brownian fashion the social function it played in the everyday lives of late Roman citizens, he offers a much more generous interpretation of our forebears’ behavior than Hume or Gibbon would. This is a welcome development. But even after celebrating his imaginative, human-focused, downright magnanimous approach to his religio-historical themes, I don’t know whether Brown actually believes any of what he so carefully describes. Like Brown, I am a Christian, and so I find that the Christian past makes claims on me. What claims does it make on him? Occasionally, the historian’s interdisciplinary methodology seems more like a turn away from the reality of religious conviction and toward a newer and more subtle interposed concept than a willingness to take belief at face value. Perhaps this ambiguity is the consequence of finding in modern historiography a substitute for the mystery of faith.

Even so, Brown’s critical approach to his subjects has softened over the years, and the assimilation of belief has been more frequently intimated around the edges of his work. Critical sharpness has given way to a warm generosity—a willingness, say, to walk back the “harshness in my judgements on the old Augustine,” as he says in his epilogue to the updated edition of the great bishop’s biography, or to entertain the possibility of making “this past part of ourselves,” as he says in his introduction to the 2008 edition of The Body and Society. Perhaps it is enough to put Hume in his place and allow one’s horizon to open out onto a wider, richer, more human landscape. Even now in his winter years, Brown remains intensely curious about late antiquity, about the past, about the world. Curious enough to say his prayers every morning and “to turn, before dawn’s early light, to reading ancient languages,” he is a historian to the end.