A Trial That Isn’t a Trial?

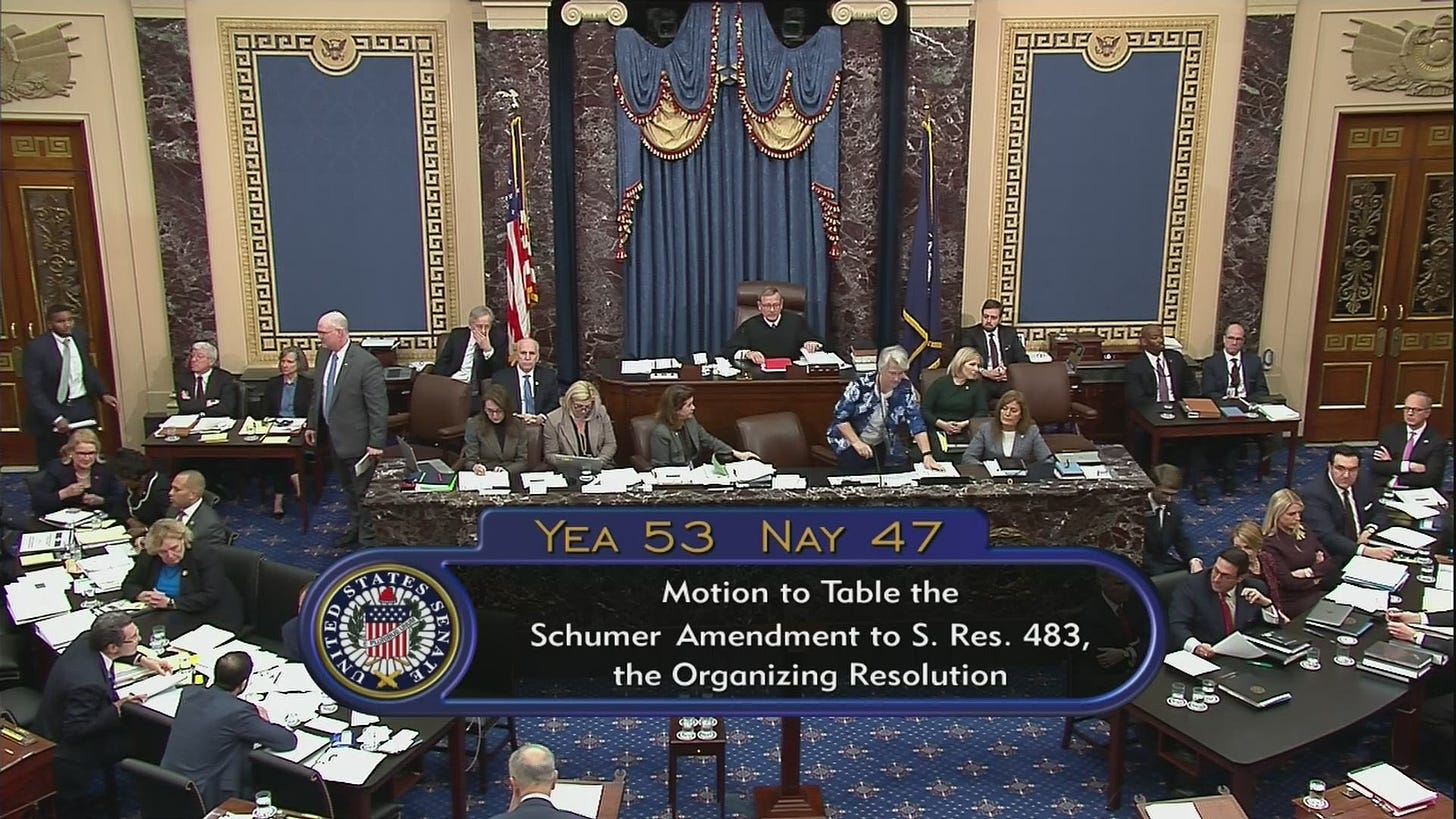

On Day One, Senate Republicans shot down House managers’ requests to bring witnesses and new evidence into the Trump trial.

In 1952, in the midst of the Korean War, President Harry Truman issued an executive order directing the secretary of commerce to take over the nation’s steel mills in order to avert a massive strike that could cripple the steel industry. The country needed steel for the war effort, and “the indispensability of steel . . . led the President to believe that the proposed work stoppage would immediately jeopardize our national defense.” Truman rationalized the action by citing his inherent power as commander-in-chief. But “the use of the seizure technique to solve labor disputes in order to prevent work stoppages was not only unauthorized by any congressional enactment; prior to this controversy, Congress had refused to adopt that method of settling labor disputes.”

If this sounds familiar, it should. The Government Accountability Office last week issued a report concluding that the Trump administration violated an act of Congress with the president’s unilateral withholding of $391 million in Senate-approved aid to Ukraine, despite his concocted rationale that the move was aimed at rooting out corruption in Ukraine. Trump’s trial brief is also rife with rhetoric insisting that he has complete authority to do what he pleases, regardless of Congress and the law, under Article II.

This week, on the first real day of Trump’s impeachment trial, it became obvious that Senate Republicans uniformly agree with Trump’s conception of unmitigated presidential power. But over a half-century ago, in Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer, the Supreme Court made clear that the argument now being offered by Trump and his Republicans defenders is dead wrong. Condemning Truman’s attempt to take over the steel mills in defiance of legislative intent, the Court, with Justice Hugo Black writing for the majority, held that

the President’s order does not direct that a congressional policy be executed in a manner prescribed by Congress—it directs that a presidential policy be executed in a manner prescribed by the President. . . . The Constitution does not subject this lawmaking power of Congress to presidential or military supervision or control.

What is really on trial this week is not Donald J. Trump. On trial is the very viability of the separation of powers, the feature of our constitutional system in which the presidency is accountable to the Congress and thus to the people. And after Day One of the Trump impeachment trial, the Constitution is losing.

There is no serious question that, in affording the Senate the “sole” power to conduct an impeachment trial, the Framers of the Constitution knew what the word “trial” means. Trials have witnesses. The Sixth Amendment—adopted by the U.S. Congress in 1789, just a year after the original Constitution was ratified—ensures a jury trial in criminal cases and provides that “the accused shall enjoy the right . . . to be confronted with the witnesses against him[ and] to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor, and to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence.” We’ve all seen this routine on television many times. Witnesses and documentary evidence are presented to a jury, and the jury decides what happened—it determines which facts reflect the truth. The Seventh Amendment accordingly preserves the common law right to trial by jury in civil cases, providing that “no fact tried by a jury, shall be otherwise re-examined in any Court of the United States, than according to the rules of the common law.” For jury trials, therefore, judges decide and articulate the law and juries decide the facts.

For an impeachment trial, senators are likewise tasked with deciding facts, which they cannot do without evidence setting forth possible versions of the facts. For Republicans to insist on a trial without evidence—as they did on Tuesday—is legally, historically, logically, and textually indefensible.

The key difference between an impeachment trial and a regular trial is that senators not only decide facts but they can also decide the law to the extent that laws reflect the rules of the game. The Constitution lays out some rules of the game for normal civil and criminal trials. Federal and state legislatures have enacted others. In rare instances, judges make up rules of the game, too. But jurors do not.

Yet the fact that senators can make up rules of the game for impeachment trials—as Senate Republicans did with Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s resolution, which was largely based on the rules adopted for the Clinton impeachment trial—does not mean that they can totally ignore the Constitution itself, which calls for an actual trial. By taking steps today to deny the American public an impeachment trial with evidence, Senate Republicans are flouting the defining document of our republican government.

To add insult to injury, this distortion of the constitutional term “trial” is happening under the passive eye of the Chief Justice of the United States, John Roberts. The applicable Senate rules give him the authority to decide on the admissibility of evidence (including, in theory, whether certain evidence is protected from disclosure by executive privilege). But if Tuesday’s proceedings are any prelude to how Roberts plans to exercise his constitutional power to preside over the trial, it’s not looking good for the Constitution. Like Chief Justice Rehnquist before him during the Clinton impeachment trial, Roberts appears to be taking on an almost exclusively ministerial role, which amounts to reading pieces of paper that are put before him and banging his gavel to confirm preordained, politically fraught decisions by the majority party.

The meta problem for Roberts—and for the Constitution—is that those decisions are in slavish furtherance of President Trump’s claims of unmitigated power.

Which branch has the courage to stick up for the Constitution anymore? By declining to issue necessary subpoenas and follow up with motions to compel administration witnesses to testify, House Democrats eschewed use of the courts to reinforce the House’s constitutional impeachment prerogative. That process takes too long, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff argued on Tuesday. But if Youngstown Sheet & Tube means anything, it means that courts would have put the “white hat” on the House Democrats in this battle of the branches. The Supreme Court in that case reiterated that the presidency is not a monarchy. The president’s defenders seem convinced that it is.