Abolish the Death Penalty

With the nation’s attention focused on racial injustice, now is the time to confront the racial disparity on death row.

The millions of Americans protesting to achieve racial justice in the wake of George Floyd’s brutal killing in Minneapolis have a lot on their plate. But there is one issue, in particular, that seems to be slipping through the cracks despite the increasingly broad agenda being pursued by the Black Lives Matter movement. Except for a few signs held by protesters, that agenda has included little about the racial injustice of America’s death penalty.

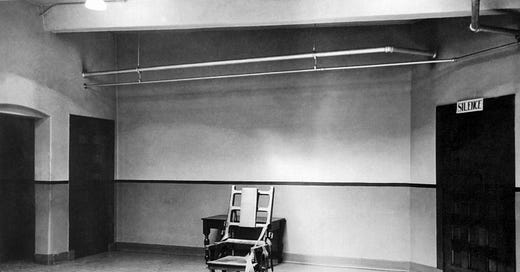

Spurred on by the horrifying images of what Floyd’s brother called “a modern-day lynching in broad daylight,” protesters are rightly pushing to reform policing and make long-needed changes in legal doctrines like qualified immunity. But the legal executions of black men, though less visible than Floyd’s death, are as tainted by racism and a history of lynching as the extrajudicial deaths at hands of the police.

While uprisings continue to upend prejudiced systems that have long evaded change, this moment also is an opportunity to call for the death penalty’s abolition.

Earlier this month the North Carolina Supreme Court reminded Americans, if they needed reminding, of the insidious ways racial discrimination plays out in capital punishment.

The court ruled that the state’s repeal of its Racial Justice Act could not stop death row inmates, sentenced prior to that repeal, from using statistical evidence to prove under state law that systemic and structural racism affected their cases.

When North Carolina enacted the Racial Justice Act in 2009, it became only the second state to allow courts to consider such evidence. But soon after Republicans took control of the state legislature in 2011, they gutted that act. They did so by requiring defendants wanting to get off death row to identify someone who acted in a discriminatory way in their particular trial. Two years later they repealed the Racial Justice Act altogether, denying its protections to the state’s heavily black, death row population.

Today, as has long been the case, America’s death penalty is disproportionately applied to persons of color. It is most frequently used in Southern states where, in the nineteenth century, lynching was prevalent, and it is impossible to decouple capital punishment from that history and its legacy of racial terror.

For almost fifty years, courts and legislatures have been called on to repudiate that legacy. But they have not found a way successfully to end racial discrimination in the death penalty

In 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court tried to do so when it determined that capital punishment was being meted out in a manner that opened the door for arbitrariness and discrimination.

In Furman v Georgia, Justice William Douglas noted, “There is evidence that the imposition of the death sentence and the exercise of dispensing power by the courts and the executive follow discriminatory patterns. The death sentence is disproportionately imposed, and carried out on the poor, the Negro, and the members of unpopular groups."

Douglas added, “Discretionary statutes are…pregnant with discrimination….”.

Four years later, the Court brought capital punishment back. In Gregg v Georgia, it decided that death penalty statutes enacted after Furman that limited and guided discretion passed constitutional muster.

Laws identifying specific factors that would make someone death-eligible, like murdering a police officer or torturing someone before murdering them, would, the Court observed, focus “the jury's attention on the particularized nature of the crime and the particularized characteristics of the individual defendant” and ensure that race played no part in death sentencing.

The Gregg decision launched an “experiment” to see if limiting discretion would prevent discrimination, but the decision really represented the triumph of hope over experience.

The hollowness of that hope was quickly exposed. Research published seven years after Gregg showed that blacks who killed whites were 22 times more likely to get a death sentence than whites who killed blacks. It also set the stage for still another legal challenge to capital punishment and its racist legacy.

In its decision in that case, however, the Supreme Court completely turned its back on Furman’s call to eliminate racial discrimination from the death sentencing.

In McCleskey v Kemp the Court acknowledged the reality of racial disparity. However, it ruled that statistical evidence, which was then commonly used to prove discrimination in housing, employment, and other areas, could not prove a violation of the 14th Amendment’s equal protection guarantee in death cases.

Writing for the majority, Justice Lewis Powell said that jury decisions were too complex to be accurately understood through a statistical lens. And, in a preview of what happened in North Carolina in 2011, he wrote that defendants would have to show “intentional discrimination” in their own cases in order to successfully challenge death sentences.

Because bias is often implicit and not all racism is as overt as it was in George Floyd’s killing, it is often impossible to provide the kind of proof that Powell demanded.

Yet we know that discrimination in death sentences not only has persisted, it has gotten worse over time. In the decade following Gregg, 46 percent of those sentenced to die were people of color; today that figure is 60 percent.

Not long after he retired, Justice Powell was asked if there was any case in which he wished he could change his vote. "Yes, McCleskey v. Kemp," he replied.

Other justices have expressed no such second thoughts. Although the Supreme Court said in 2017 that racial bias in the criminal justice system “must be confronted,” it has shown no interest in revisiting McCleskey and addressing the death penalty’s systemic racism.

Moreover, since 1994, federal legislative reform efforts of the kind that produced North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act have gone nowhere. In that year, the House of Representatives passed a federal Racial Justice Act as an amendment to the infamous Omnibus Crime Bill. But it was removed by President Bill Clinton and Senate Republicans before it was enacted into law.

With the nation’s attention focused on racial injustice, now is the time to confront the death penalty’s troubling racial history. Tools like those made available in North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act are needed to allow victims of discrimination in death sentencing to effectively make their case.

But, in the end, even those tools cannot save capital punishment.

America will never achieve racial justice until it ends the death penalty and stops what Reverend Jesse Jackson has rightly branded “legal lynching.”