About Those Empty Grocery Shelves

How real and how bad are the food supply problems?

Remember the early days of the pandemic, and the worries about shortages of toilet paper, paper towels? (And, in my household, there was also worry about baby wipes and baby food.) Concerned about the slim pickings of the quick picker upper, I went to Restaurant Depot to get those paper towel rolls you see in restaurant bathrooms—the big brown ones that aren’t perforated. My wife won’t let me live it down.

Now, in year three of the pandemic, people are worrying yet again about food. Pictures of empty grocery shelves are popping up on social media, sometimes with a Russia-in-the-late-Cold-War feel to them. Some supermarkets are responding with a little trolling.

Which raises two big questions: Is this a serious national problem, or a local problem blown out of proportion by news media and social media? And, with the pandemic still not yet over, how can we expect this situation to develop in the weeks and months ahead?

President Joe Biden addressed this concern in his stemwinder of a press conference last week:

Notwithstanding the recent storms that have impacted many parts of our country, the share of goods in stock at stores is 89 percent now, which is barely changed from the 91 percent before the pandemic. I often see empty shelves being shown on television. Eighty-nine percent are full, which is only a few points below what it was before the pandemic.

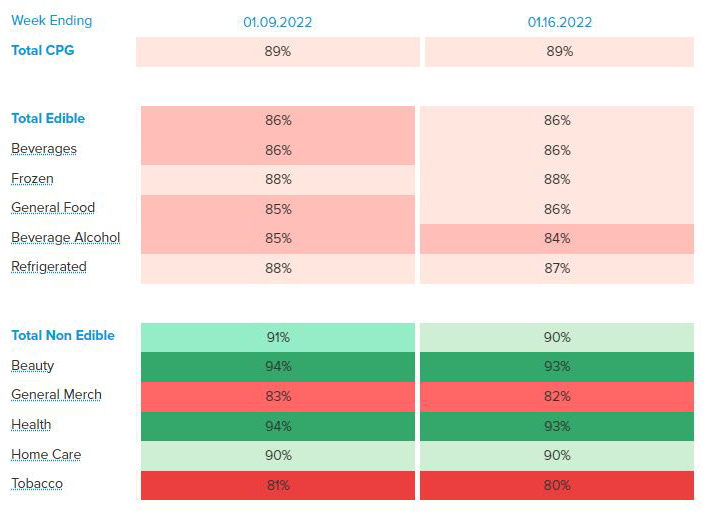

Here’s a more detailed view of the stat that Biden cited—“in-stock rates” of consumer packaged goods (CPG) at grocery stores across the whole country during the weeks ending Jan. 9 and Jan. 16:

Two things to note before digging into these figures: They cover only consumer-packaged goods, not fresh fruit and vegetables, and not fresh meat and seafood, so supplies of those critically important types of food might be worse or better than the categories shown here. And, as the Consumer Brands Association notes, even during the pre-pandemic era out-of-stock percentages tended to run from 7 to 10 percent.

The 89 percent figure Biden cited masks some real variation: When you break down the data a bit, you can see that some shelves are barer than others. Among the major food categories, “Beverage Alcohol” was in lowest supply for the week ending Jan. 16, at just 84 percent. But some subcategories were much harder to find. “Sports and energy drinks” clocked in at 78 percent. “Frozen baked goods” were down to 72 percent. And “refrigerated dough” was way down at 61 percent—the lowest of the food and drink subcategories.

And when the data are broken out by state, something striking emerges. For the week ending Jan. 16, and looking just at edible goods, every single state was marked red—meaning that overall supplies of food in stores in every state were under 90 percent. In nineteen states, supplies were between 82 and 85 percent.

So yes, there are empty shelves and shortages. And again, crucially, these stats don’t reflect fresh food, where the supply situation could be very different.

So who or what is to blame for these dips in supply? National and international supply-chain issues play into the problem. The availability of labor in the trucking industry—one of America’s biggest professions—is a major factor. A lot of people quit trucking during the “great resignation” of the last year and a half, and a lot of people became truckers for the first time.

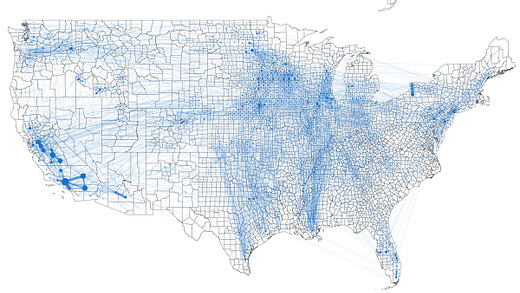

Even when grocers and their suppliers can get people to drive the trucks, wait times and traffic can play a role. Plus, geography matters: Much of the explanation for why there are grocery shortages depends upon where you’re talking about. Snowy weather can create variations even within a region: After a storm, it can be a lot harder to get an eighteen-wheeler to stock a store on a small, angular street in a badly plowed East Coast city than to get a truck to a grocery store in that same city’s suburbs right off an interstate highway. To a system as complicated as this one—

—perturbations caused by labor shortages in one place can have unpredictable effects elsewhere.

I sought comments for this article from representatives of major grocery chains. Several chains and their parent companies had no response or refused to comment. (I shouldn’t expect them to comment, one person in the industry told me, since even if shortages aren’t their fault, responding to explain the reasons for the shortages can, from a p.r. perspective, seem like admitting failure or blaming others.)

I did get a reply from a representative of Wegmans, a chain with over 100 stores in the East:

We continue to see supply chain disruptions due to raw material and labor shortages as well as delays in transportation across the industry. This is causing products to be temporarily out of stock in our stores. While we may not have every brand or variety available, we’ve leveraged both Wegmans brand and national brand suppliers to ensure we have options available for our customers in each category.

To get a fuller and more candid picture, I talked with a former grocery executive who wished to remain anonymous. Much of the problem, he confirmed, centers on the supply chain.

Consider this example: “To get a liter of V8 to the shelf is a very complicated exercise that seems easy but actually involves many different organizations and many different teams and different people within each team.”

While it’s mostly tomato juice, seven other vegetables are involved. The end product must remain consistent. But the availability of any one of those vegetables could suffer from supply chain issues. Being vegetables, they have a limited farm-to-product life. There could be issues on the farm. There could be issues trucking the ingredient to Campbell’s. There could be issues at Campbell’s factory.

And that’s just making the product. Then you have to get that product to the store, and that involves packaging it in cans or plastic bottles, then wrapping them, loading them in boxes, putting those boxes on pallets, and shipping those pallets to grocers’ warehouses. Depending on the vertical integration of a producer of a certain product, you can run into issues getting the cans or bottles, the plastic wrap for the labels, the ink to print them on, the cardboard boxes in which they go, or even the pallets.

Then you have to hit the reset button again for potential supply-chain issues because once that V8 is in the warehouse of the grocer, the warehouse itself might have its own problems, whether it’s a COVID outbreak, a labor shortage in the warehouse, or issues with the company’s trucks or their contractors.

When it all works, it’s damn near a miracle—the creative miracle of capitalism, as unforgettably laid out in Leonard Read’s famous story “I, Pencil,” but in this case for vegetable juice for boomers. But when it doesn’t work, when some parts of the complex, self-organizing miracle break down, the whole thing can seem fragile.

And we’re not done yet. Once the V8 leaves the warehouse, it goes to the store and then it has to be unpacked, inventoried, and shelved among the tens of thousands of items for sale. Here, too, the direct effect of the pandemic making employees sick and the secondary effects of the pandemic—including the national roiling of the labor market—can create difficulties.

Grocery stores have adopted Just-in-Time (JIT) inventory management, a system that was widely adopted across several industries after Toyota used it to great success. In many respects, JIT is well suited for grocery stores, especially with perishable goods like strawberries or raspberries that need to move quickly, as opposed to, say, rice or beans, which have a much longer shelf life. But JIT doesn’t work well when the supply chain is dysfunctional, as during the pandemic. JIT can leave “a lot of big holes,” according to the grocery exec I spoke with. And the holes vary: One week you might see an aisle nearly empty, and part of the reason might be supply issues, or the problem could be exacerbated by panic buying; the next week, the aisle will be completely full.

Sometimes, empty shelves during a store’s busy stretch doesn’t mean there is a shortage, just that some goods haven’t yet been restocked. Stocking takes time. Often, if a customer disappointed by an empty shelf were to come back later that same day—or even later during that same shopping trip—the shelf might no longer be empty. And with some products, such as alcohol, bread, chips, and soft drinks, some of the stocking is done by third parties who come to the store to drop off their wares, another level of interdependence that can be affected by the networked nature of supply chain problems.

All the problems we’ve discussed here are compounded when the products in question are international in origin. About a third of the U.S. imported food trade involves food imported from Canada and Mexico, usually on trucks. Imported food from most other places arrives on ships. You want out-of-season sweet onions? They come here on ships from Peru. Pineapples from the Bahamas, apple juice from China, cashews from Vietnam—ships, ships, ships. And, as you may have heard, the cargo ships are not alright these days.

President Biden tried putting a band-aid on the Port of Los Angeles’s shipping problems over the holidays, but there really wasn’t a government fix to the fact that America not only has a lack of deepwater ports, a problem we’ve long known about, but that trucking availability and the rise of costs in container shipping worsened longstanding problems.

Last year, North America’s fresh produce trade association sounded the alarm:

The cost of shipping containers has tripled or more in the past year, with estimates increasing from $3000 per container to $15,000 to $18,000, and even as high as $25,000 per container.

Those costs get passed along to consumers (assuming the product is delivered at all).

Unfortunately, the Biden administration, having failed in its quickie attempt to fix the shipping crisis, now appears to be setting its sights on the competitiveness of the meat industry. A plan released by the White House earlier this month proposes to make the meat industry more “fair”—a plan that represents the biggest government interference in the meat industry perhaps since the days of FDR’s unconstitutional National Recovery Administration. The Biden-Harris plan even includes a proposal to spend $1 billion on independent meat processors (that is, processors beyond the handful of huge firms that control most of the meat industry). If we’re going to spend billions on fixes, perhaps we should focus on things that show promise, rather than try and fight futile antitrust wars of Democratic administrations past.

One final wrinkle worth having in mind as we think about the question of the empty shelves: As Andrew Harig of the Food Industry Association pointed out to me, the pandemic has affected people’s eating habits. People are adapting and learning. Maybe our patience is wearing thin, and maybe our willingness to cook is, too. But grocers are watching and listening, and whether it’s Costco’s $4.99 rotisserie chicken (which set record sales last year), or frozen meals, or other prepared goods to cut down on cooking time, America’s grocers are here to provide. And despite the occasional empty shelves, we’re quite lucky that, compared to many other countries, our supply chain and our food suppliers are as resilient as they are.