The Bizarre Russian Prophet Rumored to Have Putin’s Ear

Aleksandr Dugin hates America and is obsessed with Nazis, the occult, and the end times.

The madness of Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine has once again turned the spotlight on the creepy, enigmatic guru who has been called “Putin’s brain” or, irresistibly, “Putin’s Rasputin”: maverick “political philosopher” Aleksandr Dugin. And indeed, in many ways this is Dugin’s moment: For more than a quarter century, he has been talking about an eternal civilizational war between Russia and the West and about Russia’s destiny to build a vast Eurasian empire, beginning with a reconquista of Ukraine. Both the war in Ukraine and the new Cold War against the West can be said to represent the triumph—or the debacle—of Dugin’s vision.

The 60-year-old Dugin may or may not be Putin’s whisperer; there is no evidence that the two men have actually met. But his influence on the Putin-era ruling class in Russia is unquestionably real and scary. For one thing, much as the word “fascist” gets frivolously thrown around, Dugin is actually a onetime self-proclaimed fascist, albeit of the “real fascism has never been tried” variety. What’s more, there is every reason to think that while he dropped the label, his ideology has not changed much.

But even that understates the sheer weirdness of the man described in a 2017 book on the rise of Russia’s new nationalism as “a former dissident, pamphleteer, hipster and guitar-playing poet who emerged from the libertine era of pre-perestroika Muscovite bohemia to become a rabble-rousing intellectual, a lecturer at the military academy, and ultimately a Kremlin operative.” (The author, former Financial Times Moscow bureau chief Charles Clover, had extensive conversations with Dugin and still failed to crack the enigma.)

For instance: Dugin has had a lifelong obsession with the occult, ranging from the legacy of magician and huckster Aleister Crowley (a 1995 video shows him reciting a poem at a ceremony honoring Crowley in Moscow) to much more sinister Nazi occultism. His first appearance on Russian television, in 1992, was as an “expert commentator” in a shlocky documentary that explored the esoteric secrets of the Third Reich, which he claimed to have studied in KGB archives. Hе now rails against Ukrainian “Nazis” but once penned a poem in which the apocalyptic advent of an “avatar” culminates in a “radiant Himmler” rising from the grave. (While he later tried to disown this verse, it was posted on his website under a name he has elsewhere acknowledged as his pseudonym.) Dugin’s oeuvre also includes a 1997 essay proposing that the notorious Russian serial killer Andrei Chikatilo, who gruesomely murdered more than fifty young women and children between 1978 and 1990, should be regarded as a practitioner of Dionysian “sacraments” in which the killer/torturer and the victim transcend their “metaphysical dualism” and become one. He talks casually and cheerfully about living in the “end times.” He preaches national and religious revival but can also, according to Clover, make such quips as, “There are only two real things in Russia: Oil sales and theft. The rest is all a kind of theater.”

Many details of Dugin’s life are obscure, no doubt due to some extent to deliberate mystification on his part. It has been claimed, for instance, that his father was either a colonel or a lieutenant general in the GRU, the fearsome Soviet military intelligence agency, and used this position both to protect him and perhaps to facilitate his access to the military and intelligence elites. Extremism researcher Anton Shekhovtsov, who has delved into Dugin’s background, asserts that the reality is far more prosaic and that Dugin père was an officer in the Soviet, later Russian, customs service. According to Clover, Dugin has claimed that his rebellious youthful antics—which included involvement, at 19, in an underground circle that dabbled in mysticism with a neofascist slant—caused his father to be transferred from the GRU to the customs service; but Clover also quotes Dugin as saying that his father never supported him and that they barely had a relationship. (Dugin’s parents were divorced when he was 3 years old.)

Expelled from college for his unorthodox activities (which included the translation and samizdat publication of Pagan Imperialism by Italian far-right intellectual Julius Evola, another fascist with a mystical bent), Dugin made a living for a while as a language tutor and freelance translator. But he clearly wanted more, and the changes under Mikhail Gorbachev—which included a drastic relaxation of state control over intellectual and political life—opened up new avenues. In 1988, Dugin got involved in Pamyat (“Memory”), a “patriotic” and “anti-Zionist” movement notorious for its anti-Semitism, but was eventually expelled for murky reasons (Satanism, according to some). He also traveled to Europe and cultivated ties with far-right figures such as French counter-Enlightenment author Alain de Benoist. Interestingly, despite benefitting from the reforms, Dugin sympathized with the hardline coup against Gorbachev in August 1991 and reportedly even tried to get weapons so that he could volunteer to fight for the coup plotters’ “State Emergency Committee.”

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Dugin became involved in various marginal groups that lived the horseshoe theory by trying to synthesize far-left and far-right ideology, including the red-brown “National Bolshevik Party” which he co-founded with the eccentric poet Eduard Limonov. (A 1992 Dugin essay tried to reclaim the term “red-brown” as a positive thing, “the natural colors of our blood and our soil”; another piece, from 1997, hailed the dawn of a new Russian fascism, “boundless as our land and red as our blood.”)

At first, Dugin’s efforts to enter public life did not get him very far; when he ran for the Duma in 1995 on a National Bolshevik platform in a St. Petersburg district, he got less than 1 percent of the vote, despite a tantalizing campaign poster promising that “the secrets will be unveiled.” Yet he was helped by mysterious connections to the Russian military: At some point during the 1990s, he became a lecturer at the senior staff college of the Russian military, the Military Academy of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of Russia. Considering that we’re talking about a neofascist crank with a fixation on the occult, this raises eyebrows.

Dugin’s true breakthrough was the 1997 book Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia, a 600-page treatise that not only sold well but made its author a respectable pundit. It also quickly became part of the curriculum at the General Staff Academy, other military and police academies, and some elite institutions of higher learning. Writing in the journal Harvard Ukrainian Studies in early 2004 (the issue is dated spring 2001 but was obviously published later, since the article refers to events from late 2003), Hoover Institution scholar John B. Dunlop concluded: “There has perhaps not been another book published in Russia during the post-communist period that has exerted an influence on Russian military, police, and foreign policy elites comparable to that of . . . Foundations of Geopolitics.”

A prolific scribbler, Dugin had published seven other books between 1990 and 1997, but Foundations of Geopolitics was his first effort to go mainstream. The earlier books had been heavy on occult lore about numerology and other mystical sciences, the lost and magical Hyperborean race, and esoteric orders such as the Freemasons, the Knights Templar and the Rosicrucians. Dugin’s 1992 book Conspirology, for example, had framed the historical conflicts between reason and faith as a literal struggle between two secret organizations, the rationalist Order of the Dead Head and the faith-and-love-based Order of the Living Heart—and that’s the condensed and coherent version.

Foundations of Geopolitics, on which Clover believes Dugin may have had help from faculty members at the General Staff Academy, offered a much more sober analysis and steered clear of mysticism and occult metaphysics. Yet the theme of a cosmic battle between good and evil was still very much a part of Dugin’s thesis. Foundations of Geopolitics posits a fundamental antagonism between “land-based” and “seafaring” civilizations, or “Eurasianism” and “Atlanticism”—the latter represented primarily by the United States and England, the former by Russia. While the idea of conflict between “land-based” and “seafaring” powers was borrowed from the fairly obscure Edwardian British geographer Halford Mackinder, Dugin reconceptualized this rivalry as a spiritual struggle, in terms drawn largely from twentieth-century German anti-liberal philosopher and prominent Nazi Carl Schmitt (with additional borrowings from earlier “Eurasianist” intellectual Lev Gumilev, son of two celebrated poets, who thought that ethnicity derived from space radiation).

In Dugin’s scheme, the values of land-based civilizations are those of traditionalism (“The hardness of the land is culturally embodied in the hardness and stability of social traditions”), community, faith, service, and the subordination of the individual to the group and to authority, while the values of seafaring civilization are mobility, trade, innovation, rationality, political freedom, and individualism. Also: Eurasian good, Atlanticist bad.

The other central message of the book is that, for Russia, it’s empire or bust. Dugin asserted that Russian nationalism has a “global scope,” associated more with “space” than with blood ties: “Outside of empire, Russians lose their identity and disappear as a nation.” In his vision, Russia’s destiny is to lead a Eurasian empire that stretches “from Dublin to Vladivostok.”

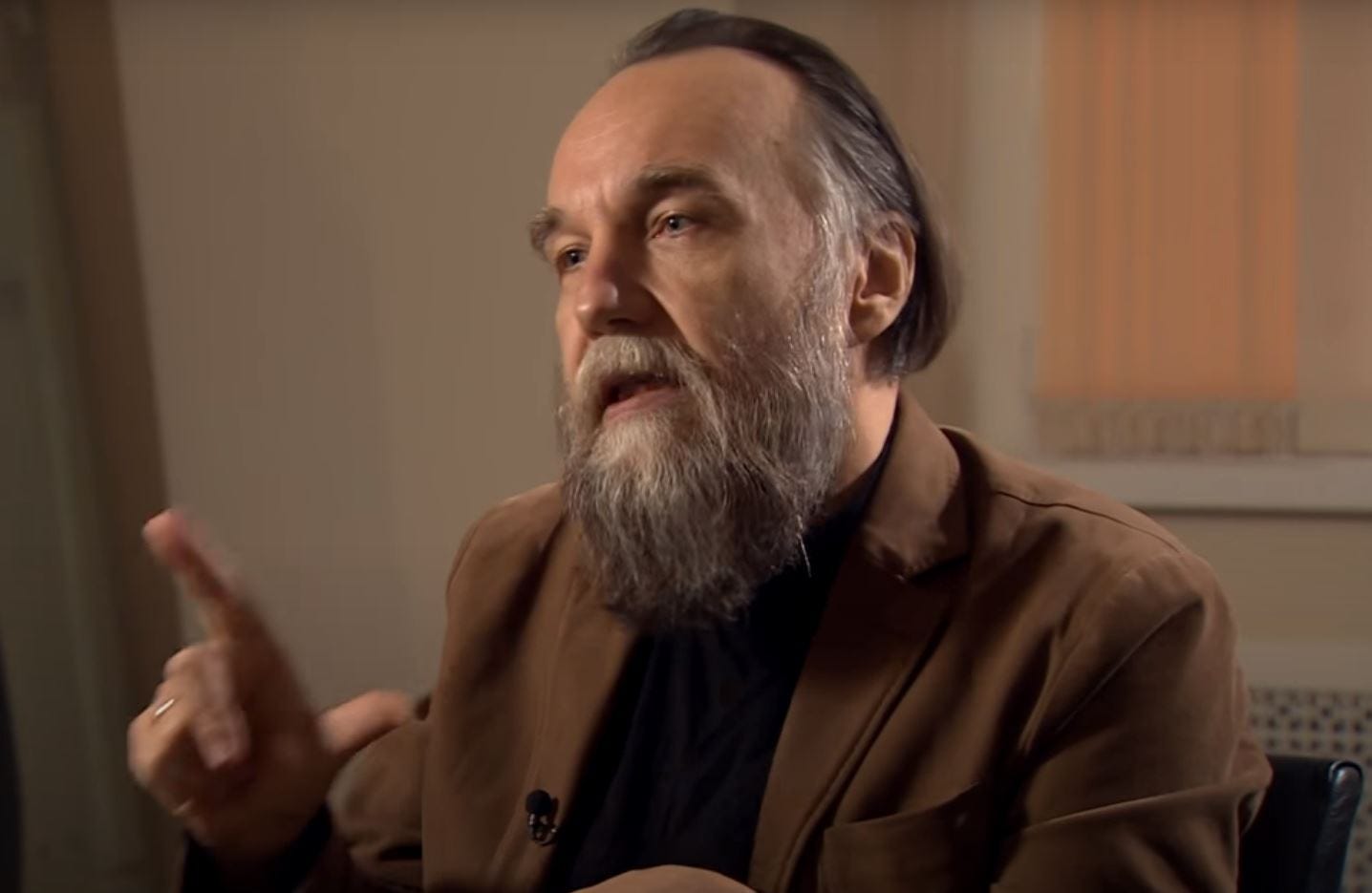

Dugin in a 2016 BBC interview.

In a country reeling from a botched transition to a market-based democracy and coping with the abrupt loss of superpower status, this call to imperial greatness fell on fertile soil—especially after the devastating economic crisis of 1998 seemed to be the death knell of liberal hopes. It was particularly welcome to the military and political elites.

In short order, Dugin, only yesterday a marginal crank, became a pundit with close proximity to power. By 2001, wrote Dunlop, he had “formed close ties with individuals in the presidential administration, the secret services, the Russian military, and the leadership of the Duma”; among other things, he had become a consultant to Russian State Duma Speaker Gennady Seleznev and to top Putin adviser Sergei Glazyev. The Russian media, then still relatively free, began to talk of “Dugin’s Eurasianism” as a new state-favored ideology. The “Eurasia movement,” which Dugin launched the same year to promote the Eurasianist agenda and resist “Atlanticist” influences, attracted government officials, members of the establishment media, and retired and current members of intelligence and state security agencies. In 2003, the movement went international, claiming to have a presence in 29 countries in Europe, the Americas and the Middle East, including 36 chapters in the former Soviet republics. Its most active wing was the Eurasian Youth Union, heavily focused on pro-Kremlin activism in Ukraine; among the group’s more notable exploits was a 2007 attack vandalizing a Moscow exhibition on the Ukrainian Holodomor, the Stalin-era terror-famine.

Toward the end of the 2000s, Dugin—armed with a hastily acquired doctorate—also completed his ascent to academic respectability. In 2009, he was appointed chair of the international relations section of the sociology department at Moscow State University (despite being a guest lecturer rather than a full-time faculty member). He also founded and oversaw a Center for Conservative Studies within the sociology department, intended to train an “academic and government elite” of “conservative ideologues.”

Should Dugin be treated as a “real” philosopher? In a recent long essay in Haaretz, Dr. Armit Vazhirsky, a historian at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, argues that, despite his (to put it mildly) eccentric history, his critique of liberalism in such works as his book The Fourth Political Theory (2009), needs to be seriously engaged.

I’m not convinced.

Dugin is a gifted man and a very erudite autodidact—unquestionably smart enough to offer a convincing simulacrum of intellectual discourse. Yet detractors such as Russian political scientist Victor Shnirelman point out that he has repeatedly and opportunistically adjusted and overhauled his arguments—for instance, transferring much of his analysis of the “Eurasian” vs. “Atlanticist” clash of civilizations from earlier writings in which the opposing forces were “Aryan” (good) vs. “Semitic” (bad). The only constant is hatred of liberalism and modernity.

As befits a practitioner of the horseshoe theory, Dugin can capably mimic and channel anti-liberal broadsides from both the left and the right. Some passages in his writings could have come straight from Jacobin magazine, arguing that liberal capitalism is responsible for the slave trade, Native American genocide, and environmental catastrophe, or that liberalism seeks to assimilate everyone to the standards of the “rich, rational white male”; other passages could have been penned by Sohrab Ahmari, such as the warning in Fourth Political Theory that liberalism’s rejection of tradition and constraints on individual freedom logically leads to “not only loss of national and cultural identity, but even of sexual identity and, eventually, human identity as well” (my translation). Then, just when you expect Dugin to defend sexual traditionalism, he invokes a gender-norm-smashing paradigm that has one left-wing commentator wondering if he is an “undercover queer theorist.”

But keep reading, and you will find text that sounds more like the musings of a genocidal maniac. For instance, the comments about the evils of unchecked liberalism in Fourth Political Theory are followed, a few paragraphs down, by this discussion of the coming battle that will happen when “the metaphysical significance of liberalism and its fatal victory” is fully understood: “This evil can be vanquished only by tearing it out root and branch, and I do not rule out the possibility that such a victory will require wiping off the face of the earth those spiritual and physical territories where the global heresy which insists that ‘man is the measure of all things’ first emerged.” In case the location of those “physical territories” is unclear, the next line urges a “world crusade against the USA and the West.”

There is little reason to think that Dugin has discarded his flirtations with Nazism (it is perhaps revealing that, in Foundations of Geopolitics, he urges Russia to form an “axis” with Germany and Japan as the core of its strategy). Nor has he moved on from his occult obsessions, despite a nominal conversion to Russian Orthodoxy—which he has tried to syncretize with various neopagan and esoteric teachings (including the work of Aleister Crowley, a reputed Satanist). A lengthy two-part essay he wrote in 2019 for the Izborsk Club, a “socially conservative” website he cofounded, returns to his old favorite Julius Evola and then segues into an abstruse discussion of Hindu and Zoroastrian eschatology.

Which brings us to another startling aspect of the Dugin persona: his fascination with the apocalyptic. The Fourth Political Theory at one point flatly states that the new theory and practice the book seeks to formulate is “invalid” if it doesn’t “bring about the End of Time.” A video of a 2012 Dugin lecture at Moscow’s New University shows him offering an eclectic stew of ideas—the Christian apocalypse, the dark Kali Yuga cycle from Hindu mysticism, the French metaphysician René Guénon, global warming—to make the case we are “obviously” living in the end times and that the end of the world is something we should actively desire. For one thing, isn’t it great to know how the story ends? For another, isn’t it terrible to be alive and know that you will never be God? And isn’t this world an illusion anyway?

The deeper one goes down the Dugin rabbit hole, the more one starts to wonder whether he believes anything he says and whether his entire career is a long, elaborate mystification. As Clover puts it, he is, “in equal parts, a monomaniacal nineteenth-century Slavophile conservative and a smug twenty-first-century postmodernist who expertly deconstructs his arguments as rapidly as he makes them.” Or perhaps, in even bigger part, he’s a charlatan. The only relevant question is whether his proximity to the Kremlin’s inner sanctum is such that his talk about the end times could be something more serious than a crazy prophet’s rantings or a postmodernist’s word games.

Whether Dugin ever actually was Putin’s éminence grise is also far from settled. Some scholars such as Finnish political scientist Jussi Backman have strongly disputed these claims, pointing out that there is no evidence of closeness between the two men. Putin, at any rate, has never mentioned Dugin in public; his acknowledged quasi-fascist guru is twentieth-century Russian nationalist Ivan Ilyin (1883-1954), whom he has quoted in several speeches and whose collection of essays, Our Tasks, he sent to Russian regional governors and senior officials for as a Christmas gift in 2013.

Dugin, on his part, has had a love/hate relationship with Putin over the years, admiring him as the leader who reclaimed Russia’s sovereignty and routed the Western-style liberals but deploring his pro-capitalist tendencies and his alliances with the West, particularly his participation in George W. Bush’s War on Terror. (The rabidly anti-American Dugin was an early 9/11 “truther,” asserting in an interview in October 2001 that the United States itself was probably behind the attacks and was using them to shore up American hegemony.) Still displaying his penchant for mystical terminology, he has spoken of the conflict between the “solar Putin,” the heroic fighter against Western evil and for Russia’s messianic destiny, and the “lunar Putin,” the pragmatic rationalist who wants a thriving economy and a partnership with the West.

He has been coy on whether or not he knows Putin personally, claiming to be “in contact” with him in a 2012 interview on the American white-nationalist website Countercurrents but flatly denying it in conversations with Clover. Most recently, when asked whether he communicates with Putin in an interview in the Russian newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets, he replied, “That’s a question I never answer.”

In November 2007, several months after Putin’s famous “Munich speech“ signaling a sharp anti-Western turn and challenging the U.S.-led international world order, Dugin made a curious comment in an interview with the Eurazia TV web channel:

In my opinion, Putin is becoming more and more like Dugin, or at least implementing the program I have been building my entire life.. . . The closer he comes to us, the more he becomes himself. When he becomes 100 percent Dugin, he will become 100 percent Putin.

And indeed, many aspects of Kremlin strategy in the Putin years reflect, to a startling extent, Dugin’s proposals going back to the late 1990s. That includes the “hybrid warfare” of subverting democracies from within and exploiting their internal divisions, something Dugin advocated in Foundations of Geopolitics. It includes cultivating both far-right and far-left movements and groups as antiliberal allies. It includes the focus on homosexuality as the ultimate symbol of Western decadence: In a 2003 interview with the Ukrainian website Glavred.info, Dugin warned that embracing a pro-Western “Atlanticist model” would expose Ukraine to the menace of “gays, and homosexual and lesbian marriage.” (Dugin’s homophobic crusade has some ironic personal twists: His former National Bolshevik associate Eduard Limonov was the openly bisexual author of an autobiographical novel that often borders on gay porn, while Dugin’s first wife and the mother of his son, Evgeniya Debryanskaya, is an out lesbian who started Russia’s first gay-rights group in 1990.)

Even the Putin regime’s preoccupation with Ukraine is anticipated by Foundations of Geopolitics, where Ukraine occupies a central place in the clash-of-civilizations scheme as laid out by Dugin. The book stresses, again and again, that Ukrainian sovereignty is an intolerable threat to the Eurasian project. “The existence of Ukraine within its present borders and with its present status of a ‘sovereign state,’” Dugin warns, “is equivalent to the delivering of a monstrous blow to the geopolitical security of Russia; it represents the same thing as the invasion of Russia’s territory.” Remarkably, this passage is from twenty-five years ago—eight years before Ukraine turned westward during the Orange Revolution and ten years before there was any talk of Ukraine joining NATO.

Clover reports that it was Dugin who revived the term “Novorossiya,” or “New Russia,” as the preferred designation for Eastern Ukraine, using it three years before Putin did. Did he inspire Putin, or merely (as he has often claimed) intuit which way things were going? Or was he floating a trial balloon at his Kremlin patrons’ behest? Nobody knows. However, it’s a fact that in 2014, Dugin was not merely cheering for the Kremlin’s “Novorossiya Project” of building pro-Russian enclaves in Eastern Ukraine but actively helping: There is a video in which he strategizes with a separatist activist on Skype. The foreign “observers” who were invited to monitor Crimea’s referendum on joining Russia were mainly drawn from Dugin’s network of “Eurasianist” political figures, running the gamut from Stalinist to fascist. Moskovsky Komsomolets reports that two of the main founders of the “Donetsk People’s Republic,” businessman and politician Aleksandr Borodai and retired military officer and possible KGB/FSB veteran Igor Girkin-Strelkov, were both Dugin acolytes.

Yet, oddly enough, the events of 2014 also led Novorossiya’s prophet to something of a fall from favor. After some overly bloodthirsty comments that urged the wholesale killing of Ukrainians who supported the “Nazi junta” and of Russians who had joined the “fifth column,” Dugin became the target of a petition urging his removal as section chair at Moscow State University. (It didn’t help that Dugin’s exhortation to “Kill, kill, kill!” on Donetsk television was followed by the claim that he was “speaking as a professor.”) Surprisingly, the university did in fact boot him, having suddenly discovered that his appointment in 2009 had been a “technical error” due to his guest-lecturer status. Dugin, on his part, took his dismissal as a sign that liberals and Satanists were winning and that the “lunar Putin” had prevailed. In subsequent months, he was harshly critical of Putin for scaling down the war in Ukraine and “abandoning” the separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk.

Now, after nearly eight years of lying low, Dugin should be the man of the hour. There seems to be very little daylight left between Putinism and Duginism, and one might say that Putin has indeed become “100 percent Dugin.” In his interview in Moskovsky Komsomolets on March 30, Dugin declared, “The solar Putin has won.”

And yet Dugin himself does not sound like a winner. Moskovsky Komsomolets may toe the government line on the “special operation” in Ukraine, but he still had to fend off uncomfortable questions about what to tell mothers who have lost their children in war zones. (His reply: “We’ll explain it all once we have liberated Ukraine.”) In the same interview, Dugin describes the “special operation” as an apocalyptic battle of good against evil, but also ruefully admits that “the Russian people are not yet fully involved” in this battle. While he suggests that a call from Putin would be enough to mobilize the entire nation, popular enthusiasm for the war is distinctly lacking so far.

In his latest piece for the Izborsk Club website, Dugin sounds a little dispirited. He worries that Russia’s leadership thinks it can declare victory after keeping Donetsk, Luhansk, and Kherson, or maybe after taking all of “Novorossiya” while leaving the rest of Ukraine “in the power of Nazis and globalists.” Dugin insists that, at this point, Russia can no longer settle for anything other than total control of all Ukraine, because “Christ needs it” and because to leave would mean the “death, torture, and genocide” of millions of Orthodox believers. Invoking his familiar eschatological themes, he asserts that “we have become not merely spectators but participants in the Apocalypse.”

Somehow, it sounds less like a passionate call to action than the words of a man who is watching his fantasies play out and go terribly wrong—and is desperately trying to stay relevant.