Algernon Blackwood’s Exploratory Horror

Tales of terrible encounters with things beyond our comprehension.

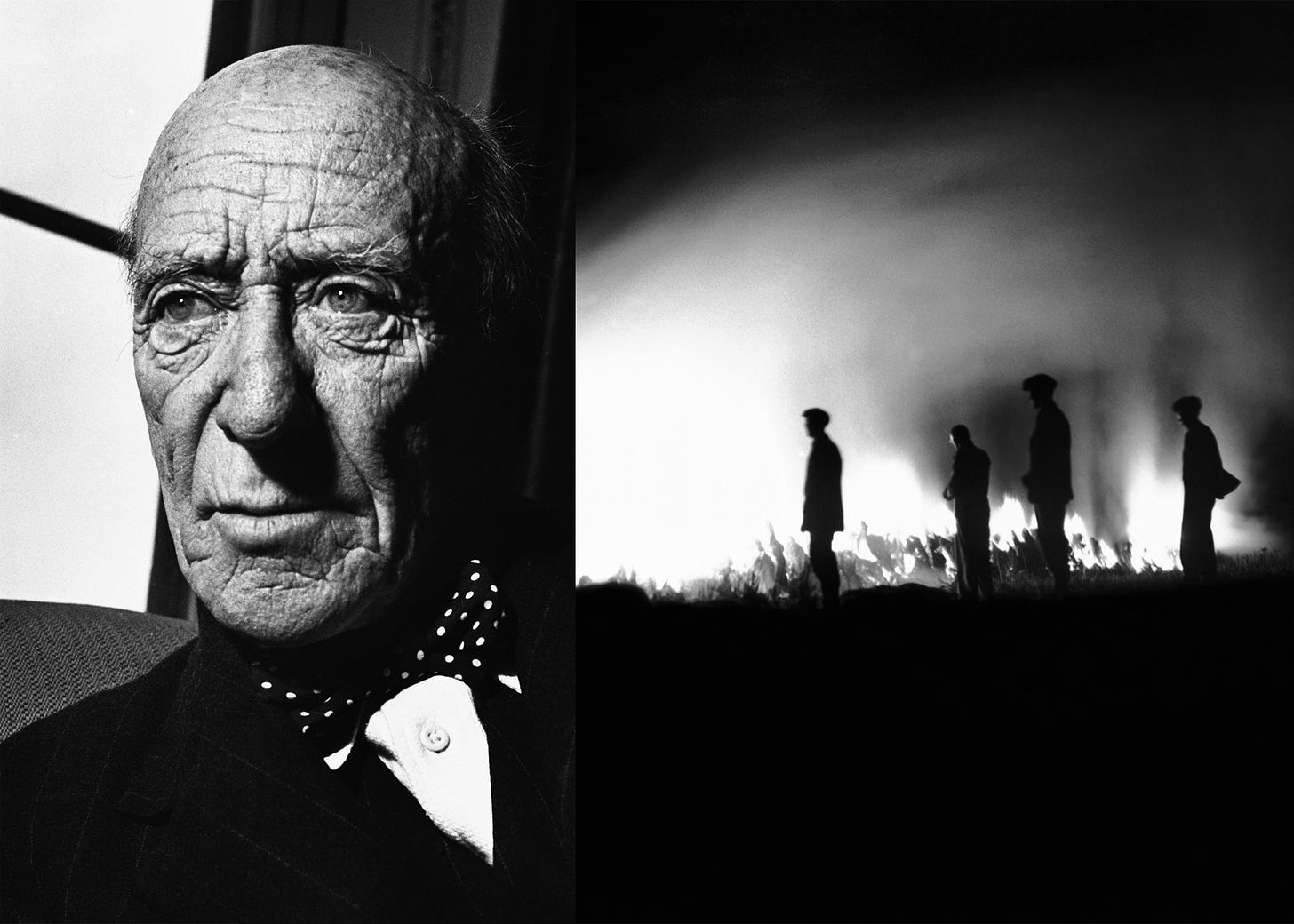

WHEN YOUR NAME IS ALGERNON BLACKWOOD, you basically have two choices: become a horror writer, or build some sort of death ray. The one man I know of who was named Algernon Blackwood thankfully chose the more peaceful of the two options (possibly because his middle name was merely Henry), and he went on to become one of the most revered authors of weird tales of the last century. He was admired by H.P. Lovecraft, with whom Blackwood is often compared (or, at other times, among horror connoisseurs, set at war against). In his long essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” Lovecraft once wrote:

[William Hope] Hodgson is perhaps second only to Algernon Blackwood in his serious treatment of unreality. Few can equal him in adumbrating the nearness of nameless forces and monstrous besieging entities through casual hints and insignificant details, or in conveying feelings of the spectral and the abnormal in connexion with regions or buildings.

That sounds about right to me. Blackwood was a very good writer, absolutely better than Lovecraft. But much of his work, particularly some of his most famous stories like “The Wendigo” and “The Willows,” remind me less of Lovecraft than Arthur Machen, a contemporary of both Blackwood and Lovecraft, whose stories, especially his classic “The White People,” often find horror not just in nature, but in the otherness that can be found there. It’s not essential that this horror is threatening; it’s enough that it forces Machen’s protagonists to wonder “What in the hell is that?” This is not dissimilar to Lovecraft, except the horror in his Cthulhu stories is the worst threat that mankind has ever faced. In Machen and Blackwood, the issue at hand is not always so malevolent. It’s like stumbling across a bear cub in the woods and realizing there’s a mother bear nearby who’s about to come after you. You’ve done nothing wrong, but deep down you understand that the bear that’s about to attack you has every right to think ill of you.

ALGERNON BLACKWOOD’S MOST FAMOUS STORY is likely “The Willows.” It was first published in 1907 as part of Blackwood’s story collection The Listener and Other Stories. In the story, two men—our narrator and his friend, known as the Swede—are in the middle of a kayak trip on the Danube. Along the way, their kayak wrecks upon a small island. The boat is not really damaged, and the two men have brought plenty of food and other provisions, so they don’t immediately view their situation as a crisis. This island is covered in thicket after thicket of willows. Of these, the narrator says they “moved of their own will as though alive, and they touched, by some incalculable method, my own keen sense of the horrible.” So, as safe as they appear to be, the men have already been made uneasy by their natural environment.

They begin to see things—not visions or hallucinations, necessarily—such as an otter in the distance swimming on its back. This, in itself, isn’t, and shouldn’t be, the cause of unease, but over the course of the story it will become so. They also see a man in a boat, waving at them to get their attention. All the two men can gather is that this man in a boat is trying to communicate something to them. But when they are unable to decipher his signals, the man resigns himself, and the last gesture the narrator and the Swede see him make is the sign of the cross.

Soon, the men start to become overwhelmed by unusually strong winds. They agree to continue their kayak trip in the morning. During the night, the narrator decides to walk around a bit, and contemplate his strange surroundings. This contemplation eventually leads him to feel an unaccountable fear:

But my emotion, so far as I could understand it, seemed to attach itself more particularly to the willow bushes, to these acres and acres of willows, crowding, so thickly growing there, swarming everywhere the eye could reach, pressing upon the river as though to suffocate it, standing in dense array mile after mile beneath the sky, watching, waiting, listening. And, apart quite from the elements, the willows connected themselves subtly with my malaise, attacking the mind insidiously somehow by reason of their vast numbers, and contriving in some way or other to represent to the imagination a new and mighty power, a power, moreover, not altogether friendly to us.

Not long after, the narrator and the Swede, hoping to get back on the water and off this island, discover that their kayak is, suddenly, badly damaged, and their provisions have been terribly depleted. Along with this, they begin to see strange things in the willows, and to hear an incessant gonging sound, the source of which they don’t know. The men eventually come to the conclusion that this island is a kind of intersection of two realities: the one they, and we, exist in every day, and a kind of otherworldly fourth dimension, from which strange things and sounds spill out into these willows. The reader, of course, can very easily see this as really an intersection between civilization and the primal forces of nature. The two men are everyday, civilized life; the willows and whatever hides within them are the essential unknowability of the natural world. The dangers of that latter world—animals, poison plants, etc.—don’t seek us out. Rather, consciously or not, we seek them out, and are alarmed when we find them. If these encounters end somehow in violence, we tend to blame anything but ourselves, even though it was we who blundered thoughtlessly into danger.

THE PRIMAL, EMOTIONLESS FURY that Blackwood writes about in “The Willows” is made more explicit in his story “The Wendigo.” In that story, again, men joyously begin a moose-hunting expedition in Canada: Dr. Cathcart and his nephew Simpson, along with two guides, Hank Davis and a strange French Canadian named Joseph Défago. There is also a Native American cook, named (for some reason) Punk, who stays behind in camp while the others are off hunting.

The hunters and guides split into groups: Cathcart goes with Davis, Simpson with Défago. Blackwood sticks with this latter pairing for the majority of the story, and Défago turns out to be the key character. There’s something about his French-Canadian origins that makes him more attuned, for better or worse, with the environment. At one point, when Défago and Simpson have set up camp, Simpson points out that this forest is far too vast to feel comfortable in. Défago responds:

“You’ve hit it right, Simpson, boss . . . and that’s the truth sure. There’s no end to ’em—no end at all. . . . There’s lots found out that, and gone plumb to pieces!”

When he and Simpson have made it deep into the looming forest, it is Défago who is quick to sense that something is off. Or, maybe not “off,” since this forest is its—whatever it is—native environment, but rather simply present. It begins with a terrible odor. Défago notices it first, and in the morning asks Simpson about it. Simpson denies smelling anything unusual, and eventually becomes frustrated when Défago pushes the issue. Simpson asks if he smelled anything. Défago says that he guesses not, that he was put in mind of such an odor because of a song he’d sung the night before, one that is sung in lumber camps: “when they’re skeered the Wendigo’s somewheres around, doin’ a bit of swift travellin.’”

After Simpson inevitably asks for an explanation, Défago describes the Wendigo as a large beast that supposedly lives “up yonder,” a magnificently enormous and incredibly fast creature that gives off an infernal odor and is repulsive to look at.

Simpson takes this all in stride, more or less, until that night when, in their tent, he observes Défago becoming seemingly possessed. He appears to be simultaneously dragged from the tent, and to leave under his own power. Either way, he’s soon gone. Simpson attempts to find him—a novice in his experience of such a forest, he nevertheless does his best. The main thing he finds is two sets of footprints: one set clearly belongs to Défago, the other to, well, something else. The footprints are gigantic, and the space between them, indicating the length of the creature’s stride, is jaw-dropping, almost enough on its own to drive Simpson mad.

The climax involves the return of Défago and much in the way of disturbing behavior, and disturbing words issued from his gibbering mouth. Punk, the Native-American cook, does become central in a kind of peripheral way, if that contradiction can be allowed. The story ends with this short paragraph:

That same instant old Punk started for home. He covered the entire journey of three days as only Indian blood could have covered it. The terror of a whole race drove him. He knew what it all meant. Défago had “seen the Wendigo.”

WITH THESE STORIES, AND OTHERS, Blackwood is writing a certain kind of folk horror. (He didn’t write this sort of thing exclusively; his John Silence stories, about a “psychic doctor,” are more in the tradition of stories about occult detectives. The most famous John Silence story, “Ancient Sorceries,” was very loosely the inspiration for Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur’s classic film Cat People.) But the work of fiction I think of first when reading these stories, apart from Machen’s “The White People,” is actually science fiction. Terry Carr’s marvelous “The Dance of Changer and the Three” tells a frightening story of American space travelers making contact with an utterly alien, but apparently friendly, species on a faraway planet. These aliens accept the astronauts into their home, feed and shelter them, eager to introduce the Earthlings to their culture. All of this ends in horrible tragedy, with the aliens doing terrible things to some of the astronauts. Once everything has calmed, the surviving, frightened astronauts angrily demand an explanation. The aliens, confused, tell them that what has occurred is simply part of their culture, a ritual that is vital to them as a race. What is there to be angry about? What is there to be scared of?

To me, this is at the heart of what Blackwood is getting at in these stories. Humans follow their need for exploration wherever it takes them. They want to learn, to discover, or to just bask in a part of the world into which man rarely ventures. They may even expect danger—on some level they may even seek it. But what they don’t expect, and don’t want to discover, is how alien this world can be, even to its most intelligent inhabitants. There may be some malice behind these terrifying, and sometimes fatal, encounters, but it’s mostly a misunderstanding, and it’s mostly your fault for being there.