Disgust and Exaltation Together

On critic and essayist Becca Rothfeld’s wild odes to excess.

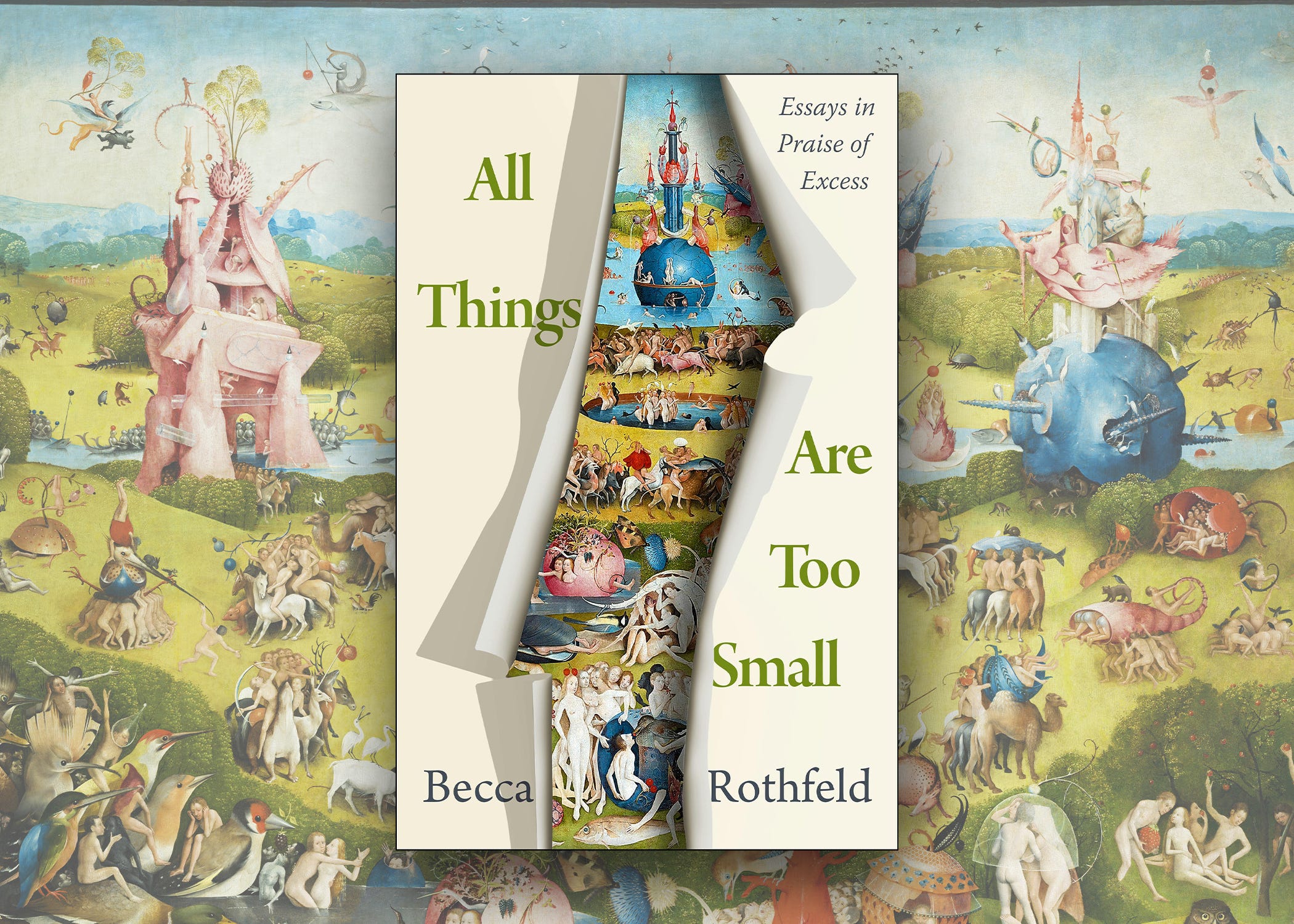

All Things Are Too Small

Essays in Praise of Excess

by Becca Rothfeld

Metropolitan, 304 pp., $27.99

THERE ARE NIGHTS IN MY YOUTH whose memory seems lit by the glow of reckless conversation. Late into the night, usually over alcohol, I’d rant and volley with my friends as we crafted our personae, trying to say things so interesting they just had to be true. This kind of talk isn’t elegant or syllogistic; it galumphs, it’s catty and clumsy, glib and unfair and sometimes infuriating. And yet it can also uncover insights so powerful and perfect that they change a life. In the excesses of my youth, there are many acts and omissions I regret. But there are also joys and truths I encountered by going too far.

That’s my best attempt to both describe Becca Rothfeld’s new book, All Things Are Too Small, and summarize its thesis. (Full disclosure: I know and like Rothfeld.) All of these essays craft Rothfeld’s persona as a defender of glut, of unslakable thirsts and wants so strong they become needs. Even when I was unconvinced by them, the vivacious confidence of Rothfeld’s arguments forced me to clarify my own thoughts. And when she swept me along, she showed me new insights into psychology and mysticism, her strongest suits.

Her weakest suit might be style—an odd thing to say about a collection so insistent on the necessity of art and beauty. The aesthetic quality of Rothfeld’s prose varies wildly across essays; I suspect that some, like “Ladies in Waiting” (previously published in the Hedgehog Review) and “Other People’s Loves” (Yale Review), benefited from a stern editorial red pen. Rothfeld loves thesaurus synonyms and mixed metaphors: “Buddhism and Hinduism were . . . sheared of cultural specificity as they were absorbed into the American morass.” So sheep are sinking in a swamp? This, from a confused essay about “decluttering” and also fragmentary novels, reads like a Maoist newspaper: “Across the Atlantic loomed the blandishments of the Baroque, but the Mayflower’s regurgitations were busy perfecting their homespun stolidity.” The criticisms that hit home are the drive-bys, like Rothfeld’s contemptuous description of minimalist home décor as “solipsism spatialized,” or sentence-long shivs like, “Each page in The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up does its best impression of a screen.”

Rothfeld argues for a surprisingly narrow vision of aesthetics: “The aesthetic resides in excess and aimlessness,” never precision or elegance. She’s numb to the feeling of being burdened by clutter, and views insatiability in purely positive terms, never as a depleting form of insecurity. Silence, negative space, voluntary poverty, being at peace: these too can be havens of inexhaustible beauty. All ascesis is too small!

The essays that have stuck with me the most are both about sex. “The Flesh, It Makes You Crazy” is a tribute to David Cronenberg and the way sexual awakening can feel like monstrous transformation, like the death of the person you thought you wanted to be. Rothfeld describes her own awakening: “the days of sick surrender,” when “I stumbled through the reek [of a city summer], sweating slickly, uneasy in my body. No one I encountered noticed anything strange about me. Shopkeepers addressed me as if I were not obscene.”

This essay is terrific art criticism and terrific psychology, with hints at transcendence through abasement: “Cronenberg’s genius consists in his rare ability to see that elevation can attend disgust.” Rothfeld exposes the sordid wriggling side of not just sexual desire, but the deeper, even more transformative longings and choices desire can provoke: “Falling in love is more like turning into a fly or contracting a parasite than it is like working out a problem in economics.” I admit I giggled when Rothfeld admits that the catalyst for her monstrous transfiguration “was eventually to become my husband.” The people who argue most persuasively for all-devouring eros are often those for whom it has lined up conveniently with traditional notions of personal integrity! Whereas those who emphasize the necessity and possibility of self-control are often those for whom self-mastery has proven elusive.

Rothfeld posits a choice “between discovering what [one] will be like in a different form and evincing loyalty to her present self.” But surely there’s also loyalty to someone else. The most wrenching speech in Cronenberg’s horror-tragedy The Fly comes after the transformation of Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) into a hideous mix of man and housefly, when he discovers that this transformation has cost him his ability to protect the woman he loves: “I’m an insect who dreamt he was a man and loved it. But now the dream is over, and the insect is awake. . . . I’m saying I’ll hurt you if you stay.” Rothfeld’s insistence that sexual desire shatters and remakes personal identity makes it difficult to understand how the marriage promise is even possible. If desire undoes my future and substitutes its own, how can I pledge that future to another person?

In “Only Mercy,” Rothfeld willfully lumps together three books as part of a “conservative” “backlash” of “puritanical” “prigs.” One such reactionary screed is by my friend Christine Emba. (I criticized Emba’s book for being too progressive.) The book-review part of this essay involves hilariously uncharitable misreadings in which Rothfeld conflates Emba and polemicists like Louise Perry so that she can attribute to Emba everything she hates in Perry.

Rothfeld comes across here as exasperated and scolding, to the detriment of both her interpretive ability and her prose. Women who found bad sexual encounters painful, even traumatic; women who find casual sex no fun; women who want babies with a man who will love and protect those babies, and maybe even get a job; people who have learned to prefer order to chaos; people who see sex as part of our connection to nature, Creation, the ecology by which we’re nourished and nourish others: “Only Mercy” treats these perspectives with contempt, when it seems sort of obvious that most people find them sympathetic. There are even moments (for example, when she argues against having sex for “the extraction of fondness”) where it seems like late-night Becca is arguing that it’s wrong to have sex in order to give and receive love.

But this isn’t the point. The point of Rothfeld’s essay, where it becomes interesting and at last beautiful, is in her own theory of what constitutes good sex. She indulges in the utopianism of the bathhouse, the transformative potential of anonymous encounters, even though her to-be-sure disclaimer explains exactly why Emba’s position is more realistic: “Romance is fraught in unique respects for those of us forced to fraternize with the enemy, and sex presents special perils for people (female or not) who are at risk of pregnancy.” Still, there’s a deep beauty and insight in her emphasis on sex as transformation and sex as play. “Some encounters crack us open like eggs, and . . . we should not be willing to live without them.” Even marriage “at its best . . . involves a commitment to the lifelong cultivation of an especially ornate carnival.”

Of course, fidelity (including to, for instance, a vow of celibacy) also cracks us open like an egg. Fidelity transforms us not solely in the moment of encounter but in all the moments yet to come. Pledging to share life with someone else closes off some possibilities for transformation, but it opens possibilities for deeper change, as we become the person we chose to be; and greater rapture, as our souls grow to meet our bodies’ capacity to unite and shelter and bear weight. Being known will always transform you more than preserving inviolate your protective anonymity. Moreover, worldviews that offer alternative paths to rapture and transformation—particularly when those paths are available equally to the asexual, the unchosen, and those who simply feel a different call—are more free, more equal, and more merciful than a worldview in which sex is the privileged site of transformation.

ROTHFELD INVITES US TO DEVELOP our own accounts of sex’s purpose. Here’s my own provisional account, which I hope is pleasurable even if unpersuasive: Sex is like play, in that it is an image of the life of a love-twined and creative God. Play is gratuitous, a perfect unity of creation and sabbath, a work that is rest. Sex is special, and violation in this realm is especially terrible in part because the sexual relationship is an image of our relationship with God: freely given, covenanted, fruitful (children are only one possible form of fruitfulness), loyal.

In “Ladies in Waiting,” a rueful and charming description of waiting for a guy to call, Rothfeld draws the parallel between waiting by the phone and the mystics’ longing for God. What might have been solitude becomes loneliness when you know for whom you are waiting. This essay ends with one of those creepy things atheists say, that the longing for God is cool because “he is by nature unattainable. . . . He never defiles the purity of agony with the weakness of relief.” What’s wrong with weakness? Why is purity preferable? I hope to attain and enjoy God. If all my religion offered was waiting and hunger, that would be sad, not admirably tough! People accuse Catholics of masochism, but at least we’re masochists who get aftercare.

But Rothfeld returns to her bad argument later and transforms it into a brilliant one—far more excessive, far more bizarre, and far more true. The essay just past the book’s midpoint, “Having a Cake and Eating It, Too,” includes the collection’s title (from a poem by the thirteenth-century mystic Hadewijch) and feels like its heart.

Rothfeld argues that beauty is, like heaven, inexhaustible. We long to get all the way inside beauty, and get it all the way inside us, and yet not to be consumed by it and not to consume it. Beauty, heaven, love are the ultimate cakes we want to eat and also have. Rothfeld quotes Marilynne Robinson’s novel Housekeeping on love as “a longing of a kind that possession did nothing to mitigate.” To have your beloved completely, and yet still long for them, not because you haven’t gotten close enough but because longing is itself a form of fulfillment, and all fulfillments are now available to you, even the contradictory ones—heaven is where parallel lines meet, the Möbius strip “where God eats us, we can eat him back.” This is gorgeous and weird, and it implies an ethics, as Rothfeld quotes Hadewijch:

The madness of love . . .

It makes the stranger a kinsman,

And it makes the smallest the proudest.

The exaltation found in disgust, the exaltation of those in the lowest place: There’s a generosity and delight in Becca Rothfeld’s philosophy that makes me love it, in spite of myself.