How the American Jeremiad Can Restore the American Soul

One of the country’s greatest rhetorical traditions still has the power to remind us of our founding principles.

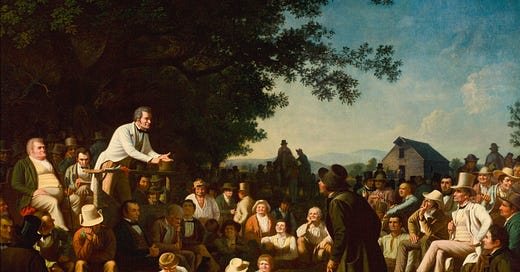

THERE ARE TIMES WHEN AMERICA’S PATH appears well marked, its destiny ordained, and its future secure. These are not such times. When America’s future is in doubt, it has often been because its identity is in doubt. It is tempting to yield to fatalistic pessimism and self-doubt, to indulge in a passive belief that our best days are gone forever. We have been through such times before, and we have a mechanism for reinventing ourselves by rediscovering our creed. This reassurance often comes in the form of the American jeremiad—a call to recommit to the American creed, a warning of disaster if we continue to stray, and a promise of redemption if we can find the strength and faith to save ourselves.

From our early history to the present, the American character has been expressed in the form of the American jeremiad. It articulates the existential and ethical imperative of American identity and purpose. The language of the jeremiad has been the instrument for insisting that America must live up to its ideals—what Jon Meacham calls “the soul of America.”

The biblical Jeremiah foretold misery and catastrophe for those who failed to adhere to the demands of their covenant with God, but offered the hope of redemption and renewal for those who returned to the practice of their faith. Jeremiah spoke of making “a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah.”

Parallel to the prophesying of the biblical Jeremiah, the American jeremiad is a message to the nation. It excoriates and condemns for moral and ethical decline, but also promises regeneration and renewal for those seeking redemption. At its core, the American jeremiad broadcasts the danger to America and the world of ending the epoch-defining experiment in freedom and self-government.

CLOSE READERS AND SERIOUS SCHOLARS of the Hebrew Bible, the Puritans emulated the Prophets in their writing and thinking. John Winthrop’s sermon of 1630, “A Model of Christian Charity,” allegedly composed aboard the Arbella that was sailing toward America’s shores, marks the origin of the American jeremiad. Winthrop’s words resonate powerfully today: “wee must Consider that wee shall be as a Citty upon a Hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.” That phrase has become a seminal statement of America as a beacon to the world. Ronald Reagan famously added the adjective “shining” to “city on a hill,” thereby reaffirming and emphasizing the example America has been, is, and must be to all humanity.

Some scholars question the time, setting, and even the history of the academic and general awareness of Winthrop’s sermon, which has become a touchstone of our national narrative and mythology. As interesting as they are, such questions do not invalidate what the sermon has come to symbolize and mean over the years.

Winthrop’s next line solidifies the sermon’s significance as a founding jeremiad. He warns that failure to live up to the responsibilities of being an example to the world will result in calamity—the people will “be consumed out of the good land whether we are going.”

At the time of the War of Independence, Thomas Paine suffused the American jeremiad with revolutionary zeal:

The Sun never shined on a cause of greater worth. ’Tis not the affair of a City, a County, a Province, or a Kingdom; but of a Continent—of at least one eighth part of the habitable Globe. ’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected even to the end of time, by the proceedings now. Now is the seed-time of Continental union, faith and honour. The least fracture now will be like a name engraved with the point of a pin on the tender rind of a young oak; the wound would enlarge with the tree, and posterity read it in full grown characters.

“We have it in our power to begin the world over again,” he continued. “A situation similar to the present has not happened since the days of Noah until now.” He proposed that “the birthday of a new world is at hand.”

The spirit of renewal and rebirth reverberates in the words of Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur, a French visitor to America who wrote in 1782, “In this great American asylum, the poor of Europe have by some means met together.” He famously continued, “What then is the American, this new man?”

The universalizing language of the jeremiad continued after the Revolution into the early republic. In Federalist No. 1, Alexander Hamilton repeated what he took to be a common observation of the day:

It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force. If there be any truth in the remark, the crisis at which we are arrived may with propriety be regarded as the era in which that decision is to be made; and a wrong election of the part we shall act may, in this view, deserve to be considered as the general misfortune of mankind.

For these eighteenth-century thinkers and leaders, America offered the world a choice for a new beginning in history.

IN THE MIDDLE OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, Theodore Parker, in his campaign against slavery before the Civil War, identified the American idea as the Jeffersonian trinity: the equality of people, the inalienability of their rights, and their opportunity to use those rights as they saw fit.

Henry David Thoreau’s symbolic journey to Walden on July 4, 1845, was a personal act of independence from the corruption and hypocrisy of his day. Harvard scholar of the American jeremiad Sacvan Bercovitch says of Thoreau, “Like a biblical prophet, he hoped to wake his countrymen up to the fact that they were desecrating their own beliefs.”

Thoreau’s expression of the American jeremiad advances the idea of America as, in Bercovitch’s words,

a country that, despite its arbitrary territorial limits, could read its destiny in its landscape, and a population that, despite its bewildering mixture of race and creed, could believe in something called an American mission, and could invest that patent fiction with all the emotional, spiritual, and intellectual appeal of a religious quest.

For Bercovitch the debate over the meaning of America as structured by the American jeremiad has been the dominant theme of American literature and culture. Bercovitch calls American writers, including the writers of the nineteenth-century “American Renaissance”—Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, and Melville—“American Jeremiahs, simultaneously lamenting a declension and celebrating a national dream. Their major works are the most striking testimony we have to the power and reach of the American jeremiad.” (Emphasis in original.)

As described by Bercovitch, the American jeremiad works like what, in another context, he calls “the American method for self-perfection.” Thus, the structure and history of the modern American jeremiad enables the continued striving through history of the demand for America to nurture, deepen, and expand the classic American creed: compassion, fairness, hope, and renewal.

For both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, the American jeremiad mapped out the moral and ethical geography of the Civil War. They both used its forms and conventions. In a sense, Lincoln’s presidency was the enactment of a living American jeremiad. Just as the anxiety over renewal or destruction infuses the very form of the jeremiad, the Civil War was fought to decide the life or death of the Union.

Lincoln’s sharp and provocative 1862 “Second Annual Message” (what we today call the State of the Union address) exploited the structural tension of the jeremiad to dramatize the stark alternatives facing the nation. Telling Congress that “we cannot escape history,” he proclaimed, “We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best hope of earth.”

Lincoln’s words tightly encapsulate the psychology and history of the jeremiad. He transforms and directs Winthrop’s prophetic vision of an ideal city on a hill to the living reality of his time—the distinct possibility, even likelihood, of losing forever the opportunity America offers for people to create their own destiny in freedom. He makes the choice and the situation concrete, specific, and immediate by emphasizing that only freedom for the slave can protect and preserve freedom for all people. Lincoln says, “We know how to save the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it. We—even we here—hold the power, and bear the responsibility. In giving freedom to the slave, we assure freedom to the free.”

In the following year’s Gettysburg Address, Lincoln asserted the national hope and the promise of the American experience that made the country unique in human history: “a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Lincoln immediately moves to warn of the possibility of losing all that had been gained since the founding through the extraordinary work and sacrifice of others: “Now we are engaged in a great civil war testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and dedicated can long endure.” In this crisis, Lincoln the prophet emerges.

Keeping with the form and mode of the jeremiad, Lincoln concludes his address with the immortal words of renewal and rebirth. He declares “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.” Invoking God while also holding out the danger of ultimate loss and disaster enriches and strengthens Lincoln’s message with a biblical tone and mood consistent with the form of the jeremiad.

By Lincoln’s second inauguration, he and Douglass had become friends and allies. After years of skepticism and distrust of Lincoln, Douglass came to regard him with near veneration. He said of Lincoln, “There seemed at the time to be in the man’s soul, the united souls of all Hebrew prophets.”

Douglass became, in historian and biographer David W. Blight’s phrase, a “Black Jeremiah.” Throughout his authoritative biography, Blight positions Douglass and his work in the context of the American jeremiad. Calling Douglass “an American Jeremiah chastising the flock as he also called them back to their covenants and creeds,” Blight notes, “American Jeremiahs wove the secular and sacred together in their repeated warnings and appeals for higher strivings.”

Douglass attacked slavery as a failure of the meaning of America, a violation of the spirit of the founding documents, and an abomination of the Bible’s basic ethical and moral teachings. Blight calls Douglass’s 1852 Fourth of July speech—actually delivered on July 5 as a note of ironic and bitter protest—“one of the greatest speeches of American history.” In the rhythms and cadences of the jeremiad, Douglass challenged America to live up to the meaning of July 4th by contrasting the promises of the Revolution with the realities of slavery. “Above your national, tumultuous joy,” he said, “I hear the mournful wail of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday are today, rendered more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them.”

THE TRADITION OF THE AMERICAN JEREMIAD can be found even in Gen. Dwight Eisenhower’s message to the Allied Expeditionary Force on D-Day, in which he told those in his command that “The eyes of the world are upon you” because they were undertaking a “Great Crusade” for “liberty-loving people everywhere.”

More recent examples of the American jeremiad include Ronald Reagan’s warning that “freedom is never more than one generation from extinction” and even in his campaign slogan “It’s morning in America,” as well as in Barack Obama’s frequent reminder, “That’s not who we are.”

Lately, the foremost exemplar of the American jeremiad has been President Joe Biden. He launched his 2020 campaign with a pledge to defend the “soul of this nation” and has returned to this topic throughout his presidency. Most recently, in his State of the Union address, he declared, “my purpose tonight is to both wake up this Congress, and alert the American people that this is no ordinary moment.” He concluded,

I see a future where we defend democracy not diminish it. . . . Above all, I see a future for all Americans! I see a country for all Americans! . . . Because I believe in America! I believe in you, the American people. You’re the reason I’ve never been more optimistic about our future! So let’s build that future together! Let’s remember who we are! We are the United States of America. There is nothing beyond our capacity when we act together!

This understanding of the meaning and history of America suggests that we stand today in danger of losing not only democracy for the American people but also a democracy that has been the hope and promise for the world.

The American jeremiad is meant for difficult times. It is designed for exigencies and challenges. It creates tension and uncertainty by combating moral and ethical complacency, indifference, and failure—and by demanding the effort and commitment to overcome the challenges before us.

A broad range of conflicting emotions inhere in the American jeremiad. The form cultivates dread, fear, and anxiety while also inspiring hope, confidence, and faith. It can balance confidence against fatalism. At its best, it can encourage and motivate action and structure belief.

The rhetoric of the American jeremiad can help us decide who and what we are and what we can overcome and achieve as a people. Without the guidance of the ideals and values that made the past a usable foundation for the future, we are bound to wander aimlessly, unsure of ourselves. With that knowledge, building a new and worthwhile life and future together becomes possible.