America’s Nuclear Umbrella Is Open and Must Stay Open

There’s no alternative to the American deterrent—not for the United States, and not for Europe.

MANY EUROPEANS ARE BEGINNING to question (some honestly and some self-servingly) whether the United States’ extended nuclear deterrent still provides a shield over its allies. In fairness, this is a time for some transatlantic introspection. That said, it is also a time to be clear-eyed about what can and cannot be accomplished.

First, despite the official statements and pundits’ predictions emanating from Europe, there is no indication that the Trump administration is planning to modify the United States’ more than seventy-year pledge to use our conventional and nuclear forces to defend NATO. In a February 27 press conference, Trump affirmed his support of NATO’s key Article 5, a statement later confirmed to NBC News by a National Security Council official in a written statement that said: “President Trump is committed to NATO and Article V.”

Second, there is no European substitute for the U.S. nuclear umbrella. The independent British deterrent, while committed to NATO and coordinated with U.S. forces in NATO plans, is designed principally to impose unacceptable costs on Russia in response to an attack on Britain—and therefore to deter such an attack. But it has always been assumed that the U.K.’s extended deterrence commitments would be supported by much larger and more flexible U.S. forces. As for France, despite recent, repeated posturing by President Emmanuel Macron that the French nuclear deterrent force can assume the role currently played by the United States, the so-called force de frappe—by design and by doctrine—is, as French Defense Minister Sébastien Lecornu stated in late February, “French, and it will remain French.” Lecornu has also specifically rejected any pooling of France’s nuclear weapons capability. A strategy of “tearing an arm off the aggressor” may have made sense in the Cold War, when American nuclear forces were always the ultimate backstop (or backup), but such a strategy cannot be a substitute for the U.S. defense commitment under Article 5.

NATO, for over sixty years, has followed a policy of “flexible response,” planning to deter aggression by threatening to respond as the situation requires. NATO’s integrated response plans are developed according to this principle. NATO nations agree on a combined nuclear policy by participating in a variety of NATO forums, especially the Nuclear Planning Group. Some NATO nations have committed their aircraft to carry out wartime missions carrying U.S. nuclear weapons, while those planes (and American ones) are protected by fighters from other NATO states.

From the beginning of its nuclear weapons program, France has refused to take part in coordinated NATO activity involving nuclear weapons policy or planning. (One of the authors of this article was intimately involved in reaching out to the French in this regard for over a decade.) It has disdained joining NATO’s nuclear forums, even as an observer. It is notable, in this regard, that even when France returned to the alliance’s integrated military structure in 2009, it specifically chose not to join the Nuclear Planning Group. Its nuclear doctrine differs dramatically from NATO’s, advertising rigidity rather than flexibility. Even accepting the extremely unlikely hypothetical (for the sake of argument) that French policy would change, it is inconceivable that Paris would share with other allies the burden and risk of its nuclear deterrent, which was entirely predicated on the need to maintain national sovereignty.

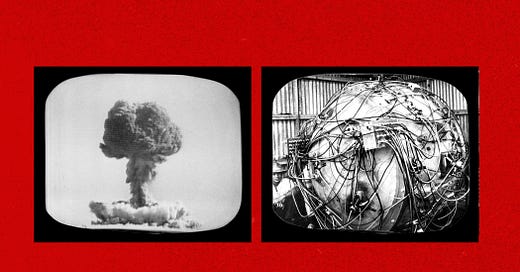

Third, the idea that NATO would be strengthened if two or more of its members opted out of the Non-Proliferation Treaty to develop their own nuclear weapons is risible. Opening Pandora’s box to allow proliferation will create global uncertainties, as European proliferation would almost certainly propel proliferation elsewhere: There is a growing discussion in South Korea about restarting its nuclear weapons program, and the greater Middle East could see a proliferation race among several rival powers. A proliferated world, in which the possibility of the actual use of nuclear weapons is dramatically higher, would be extraordinarily dangerous. Even allowing the argument that the new nuclear states themselves might be more secure against direct coercion and aggression, the rest of Europe would be left in the cold. The American nuclear umbrella has been the most effective nonproliferation policy imaginable.

Finally, the idea that the United States should establish a nuclear weapons site in Poland (at the cost of hundreds of millions of dollars) is unlikely to fly with a Trump administration already seeking to cut infrastructure funding. It might even, paradoxically, be more of an accelerant than a deterrent, since it might become a tempting target for Russian pre-emptive strikes in a crisis. If Warsaw desires a nuclear role, it should have some of its pilots join existing NATO dual-capable squadrons.

The answer, however unsatisfactory to those neo-Gaullists seeking to achieve the impossible dream of a French-led Europe, is that every effort must be made to keep the American umbrella in place—and even to strengthen it—in the near term with a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile and in the mid-term with a standoff weapon for NATO’s dual-capable aircraft. If the French are serious about strengthening deterrence rather than virtue signaling about the European dimension of their independent deterrent, they should consider how Paris can practically add to NATO’s collective nuclear deterrent capabilities. A first step would be to join the Nuclear Planning Group, its subordinate bodies, and the alliance’s nuclear planning arrangements.