Amoral Fiction

Charles Willeford’s novels portray the weird and evil as no more of a spike on the EKG of everyday life than eating breakfast or reading a magazine.

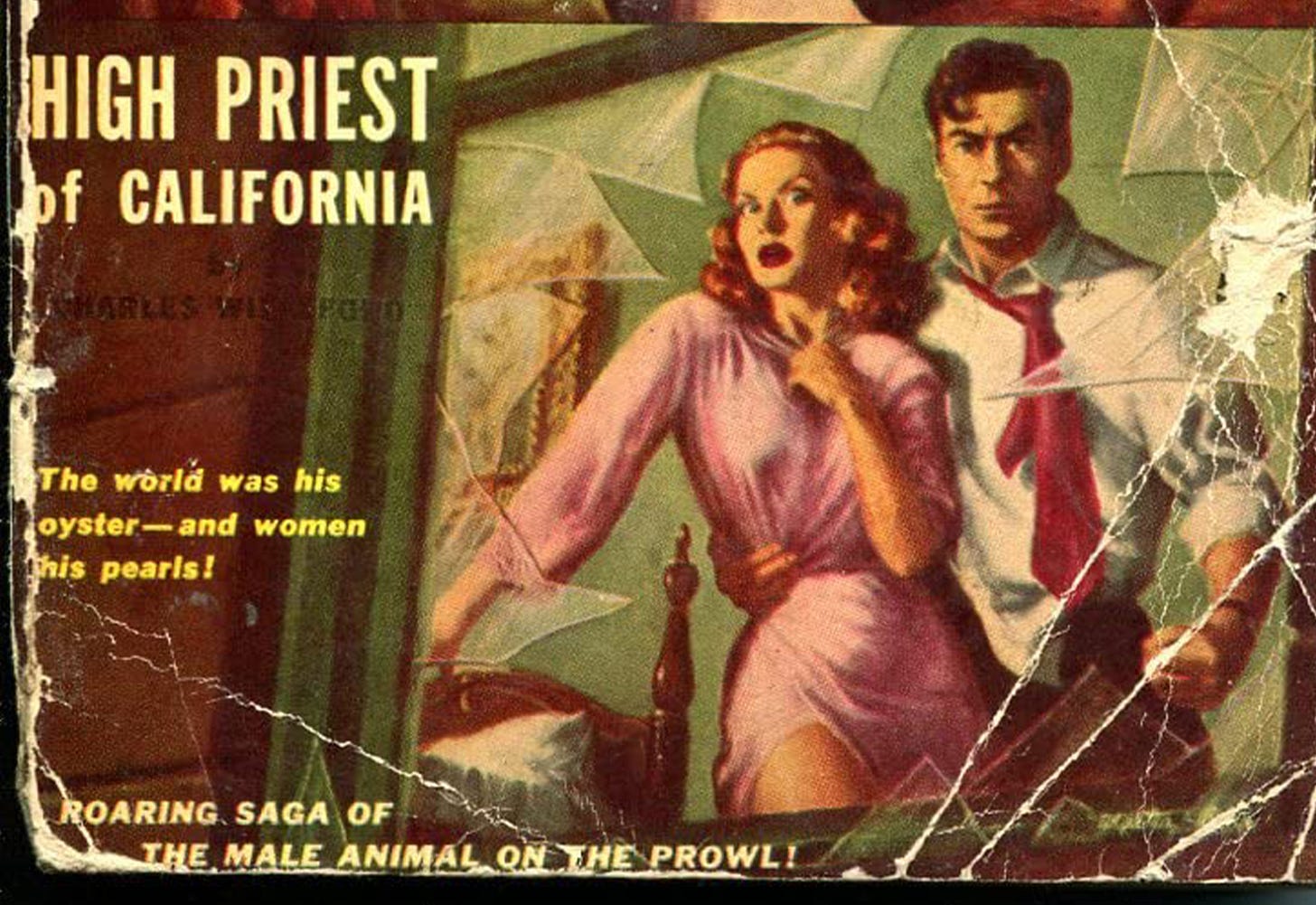

In 1984, St. Martin’s Press published what would turn out to be the most famous book ever written by Charles Willeford, an author of idiosyncratic and morally chilling crime novels. Willeford had been laboring in the salt mines of genre fiction since 1953, when his first novel High Priest of California was released. At age 65 in 1984, it looked as though Miami Blues, about a psychopath ex-con who steals the badge of Miami police sergeant Hoke Mosley and blows through the Florida metropolis both committing and stopping crimes, would finally break him out. Willeford’s agent insisted the author turn Miami Blues, intended by the writer as a stand-alone work, into the first of a series of novels featuring Mosley, detective series being the most successful kind of crime fiction out there. Willeford’s initial response was to write a novel called Grimhaven, in which Mosley, about halfway through the story, murders his two teenage daughters.

It was never published.

Willeford would eventually capitulate to his agent’s demands and write three more Mosley novels—these were actually publishable, though they read almost as standalone books in which Hoke Mosley appears—earning himself the biggest advance of his career for The Way We Die Now. The fourth Mosley novel was released in 1988, the same year Willeford died at age 69. But Grimhaven is an illustrative novel in the writer’s bibliography. When I read it—a PDF of the manuscript, which is housed in the Bienes Museum of the Modern Book department of Broward County’s Main Library in Fort Lauderdale, has been passed among Willeford diehards like samizdat for years—I was struck not only by how shocking it is, but also by the fact that if the main character had been named anything other than Hoke Mosley, the shock would be rather dampened, and it would probably read as a “normal” Charles Willeford novel. Willeford’s fiction is often blunt in its violence, sometimes blunt in its sex (the second Mosley novel, New Hope for the Dead, is particularly, uh, notable in this regard), and always blunt in its moral assault on the reader.

None of which is to say that Willeford’s novels are devoid of more traditional entertainment value. They are suspenseful, gripping, funny (if often grimly so), and exceedingly well-written. It’s just that his handle on humanity and psychology, two of aspects of crime fiction that are most vital to its success (or failure), is rather unlike how most writers approach them. Willeford begins Something About a Soldier, one of two memoirs, with this quote from Edmund Wilson:

The author’s work, no matter how intelligent, elaborate . . . or rich and vigorous in imagination, always turns out to constitute a justification for some particular set of values, a making out a case against something or other in favor of something else, a melodrama in which, even if the hero is actually defeated, he is morally triumphant—and the hero may not be a person or persons but merely certain qualities and tendencies.

Like Wilson, Willeford rejects this value-justification as a literary necessity. Literature does not require, and should actively avoid, its own self-imposed version of the Hays Code.

And Willeford always wrote this way. He emerged fully formed. The casual, motiveless cruelty of Russell Haxby, the narrator of High Priest of California, predicts Neil Labute’s 1997 film In the Company of Men, but Willeford crafts his story’s final impact with none of that film’s high-mindedness. Wild Wives (1956) ends on a note of violence—perpetrated by another narrator who I wouldn’t trust to cut my lawn—that, for reasons I’m unable to put my finger on, has never faded from my memory, though I’ve read the novel only once. The Difference (1971) is a Western, though like so many works in that genre it is still essentially crime fiction, and is exactly the kind of Western you’d expect Willeford to write, featuring as it does a protagonist with ambitions to be a legendary gunman who practices his aim by shooting a sick, decrepit old Native American man he finds leaning against a tree. On the other hand, Pick-Up ( 1954) is really a story about a couple’s alcoholic dissolution, which also reveals what kind of book you’ve actually been reading in the penultimate sentence. And Willeford’s unusual 1962 novel Cockfighter is about a man who wishes to be the best in world at that titular profession, and who after one particularly disastrous match refuses to speak until he wins again. The cockfighter is also an improv jazz guitarist. So, not a crime novel, unless you think the illegal nature of cockfighting covers that base.

There are two Willeford novels that, in my view, are especially valuable for drilling down into the heart of what he was all about. The Woman Chaser (1960) is about a dishonest, possibly psychotic, used car salesman named Richard Hudson with dreams of becoming a filmmaker. Much of the plot involves his attempts to obtain funding for the film he’s written and wants to direct, The Man Who Got Away. He enlists his father-in-law, former Hollywood bigshot Leo Steinberg, to help him get a meeting with a studio executive referred to simply as THE MAN (all caps per Willeford). Hudson describes the plot of his film to Leo, saying it’s about a truck driver with a miserable home life who takes a run on his day off. Along the way, tired from driving all night and having taken a few belts from a pint of liquor he brought with him, he runs over a little girl. Then he flees the scene:

“Okay. Here he was, a nobody. But now, all of a sudden, he’s the most important man in California! The entire state is interested in him. He’s done something! . . . Roadblocks are erected and he ploughs right through them. He has this enormous monster of a semi and nothing can stop him. SA highway patrol car gets after him but he forces it off the road and the two patrolmen are killed. Now they are really after him!”

After crashing through a roadblock, he and his truck are engulfed in flames. One person in the crowd observing the conflagration attempts to beat out the fire and possibly save his life but the rest of the crowd attacks the man. The police fire into the burning body of the truck driver.

“The final scene. The poor guy who tried to help the truck driver gets to his feet. His mouth is bleeding… He asks one of the policemen, ‘Why did everybody turn on me?’ . . . The policeman is very serious. ‘You tried to help him. That’s why.’”

So that’s the movie Hudson plans to make. As the novel proceeds, it’s clear that not only is Hudson the truck driver, he knows he’s the truck driver. And whatever crimes he, or his fictional alter ego, are guilty of, it’s everyone else who’s the problem. The desire to lead a life completely untethered from any restrictions imposed (arbitrarily, Hudson would probably argue) by society blots out all other considerations, moral or otherwise.

But for my money, Willeford’s masterpiece is the one—and this may be the first time in publishing history that such a claim can be made—published posthumously. Written in the 1970s, The Shark-Infested Custard was, Grimhaven-like, deemed too dark to publish, and only came out in 1993, five years after Willeford’s death, due to his blossoming reputation, one of the lasting legacies of George Armitage’s 1990 movie adaptation of Miami Blues. The Shark-Infested Custard, a fragment of which was published independently as Kiss Your Ass Goodbye in 1987, is really a series of interconnected novellas about four bachelors—Ed, Larry, Don, and Hank—on the prowl in Miami. Each section of the book is told from a different man’s point of view (in one case, the POV is shared by Don and Eddie), and each section focuses on a new scheme, or crime, or bit of lecherous sociopathy.

In the first story, told by Larry, three of the men bet Hank that he can’t pick up a girl at a drive-in movie theater, which for various reasons everyone but Hank considers impossible. However, Hank does pick up a girl; subsequently, she dies of a drug overdose. Trying to cover themselves, the quartet confront the man the young woman told Hank she was going to meet at the theater. The man is interrogated, at gunpoint. Then the gun, held by Don, goes off, and the man is killed.

As it transpires, Ed, Larry, Don, and Hank are able to dispose of the bodies in a way that satisfies them all and ensures this will not come back on them. In the aftermath, Hank suddenly remembers something:

“Just a minute,” Hank stopped us. “I picked up the girl in the drive-in, and bets were made! You guys owe me money!”

We all laughed then, and the tension dissolved. We paid Hank off, of course, and then we went to bed. But as far as I was concerned, we were still well ahead of the game: four lucky young guys in Miami, sitting on top of a big pile of vanilla ice cream. The novel moves on from this situation, but it quietly reverberates throughout, until it ends with an ingenious, blackly funny punchline. In the end, The Shark-Infested Custard reads as crime fiction at its most frightening, matched only by Jim Thompson at his most unhinged.

Willeford’s novels portray the weird and evil as no more of a spike on the EKG of everyday life than eating breakfast or reading a magazine. With very few exceptions, the violence in his fiction has little psychological impact on those who commit it. It doesn’t break them, because there is nothing in them to break. Taken as a whole, his bibliography reads like his attempt to dramatize a quote from Blaise Pascal, which Willeford used as an epigraph twice, in New Hope for the Dead and Grimhaven: “Man’s unhappiness stems from his inability to sit quietly in his room.”