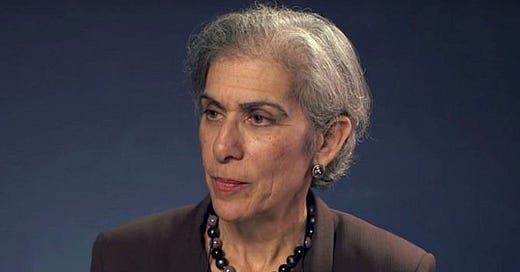

Amy Wax’s “White” Race

University of Pennsylvania law professor Amy Wax caused a stir last week with her comments during a panel on immigration at the National Conservatism Conference. Wax informed the audience “that our country will be better off with more whites and fewer nonwhites.”

This was not the first time Wax has made unpleasant declarations about race. In 2017 she told Glenn Loury on the video chat site Bloggingheads: “Here’s a very inconvenient fact, Glenn: I don’t think I’ve ever seen a black student graduate in the top quarter of the class, and rarely, rarely, in the top half.” She later admitted that she had no data to support this statement.

Wax may be brilliant—she graduated summa cum laude in molecular biophysics and biochemistry, earned a medical degree from Harvard, and a law degree from Columbia—but when it comes to race, she is, to be generous, myopic.

The definition of what it means to be “white” in America has always been fraught. Unlike ethnicity, which has at least some basis in shared DNA, the quality of “whiteness”—or “non-whiteness”—is both amorphous and transitory, defined differently at various points in our history, usually depending on who was doing the defining.

The eugenicists who pushed through broad-scale immigration restriction in 1917 and 1924 were obsessed with classifying races. Madison Grant’s influential book The Passing of the Great Race defined a hierarchy of European races, with “Nordics” at the apex, “Alpines” in the middle strata, and “Mediterraneans” on the lowest rung. Grant and other restrictionists of the era argued that the United States was being flooded with inferior peoples from Southern and Eastern Europe, who were diluting the stock of native-born Americans, namely from the British Isles and Northwestern Europe. He argued that native-stock Americans “will not bring children into the world to compete in the labor market with the Slovak, the Syrian, and the Jew,” who, he claimed “adopt the language of the native American, they wear his clothes, they steal his name, and they are beginning to take his women, but they seldom adopt his religion or understand his ideals, and while he is being elbowed out of his own home, the American looks calmly abroad and urges on others the suicidal ethics which are exterminating his own race.”

Wax and her fellow travelers among nationalist conservatives make the case that today’s immigrants are culturally unfit to become Americans. Using a metaphor associated with the alt-right, Wax dismisses the idea that the “magic dirt” of American soil will transform immigrants into Americans—a straw man argument not made by any serious immigration proponent—and claims that there is no reason to believe that “people who come here will quickly come to think, live, and act just like us.”

This is an odd argument for Wax, who is Jewish—or any grandchild or great-grandchild of immigrants—to make. Yet the restrictionist right is filled with examples of individuals (Wax, John Fonte, Mark Krikorian) who would apply standards to today’s immigrants that would have kept their own forebears from immigrating to America had they not made it in before restrictions were imposed in 1924. The early 20th-century restrictionist legislation was intended to keep out Jews, Italians, and Armenians (among others) on the grounds that they were culturally, if not actually physically and intellectually inferior.

Yet those early 20th-century immigrants did assimilate, despite being in many cases far more “culturally incompatible”—as Wax phrases it—than today’s newcomers. Assimilation took time, usually three generations to be fully realized, but it not only occurred for the progeny of Yiddish-speaking arrivals from Russian shtetls but for illiterate Italian peasants and millions of others.

The assimilation process was not always smooth. It took Italian-Americans until 1971—some 60 years after their peak immigration—to catch up in average education and earnings with other Americans, and many German-Americans continued to insist their children attend German-language schoolsin Wisconsin, Colorado, and elsewhere well into the 20th Century.

But assimilate they all did—as second-generation Hispanic- and Asian-Americans are assimilating today. They universally learn English, graduate from high school and college in increasing numbers, and marry outside their own groups—often more quickly than previous immigrant groups did. Moreover, even among Hispanics, who seem to arouse the greatest anxiety among the restrictionists, ethnic identity fades in successive generations, with only half of 4th-generation Hispanics self-identifying as “Hispanic.”

But qualifying as American, much less as “white” to Amy Wax, is all in the eye of the beholder. It might surprise Wax to learn that a majority (53 percent) of self-identified Hispanics in the last census listed their race as “white.”

And Wax’s cultural argument isn’t any more persuasive than her racial one. In an article last year in the Georgetown Law Review, Wax points to race-baiters Enoch Powell, Laurence Auster, and John Derbyshire to bolster her arguments and bemoans that “thoughtful discussion of these positions is effectively banished from public fora and relegated to obscure corners of the internet on independent blogs or at online sites such as VDARE, The Journal of American Greatness, Taki’s Magazine, and Jacobite.”

With these publications as her models for discussion, it’s no wonder Amy Wax comes off sounding like a bigot.