‘An Increasingly Dangerous Place’

Plus: The U.S. bureaucratic reshuffle that helped Israel neutralize Iran's attack.

Some real possible progress in the House on Israel and Ukraine aid at last, per the AP: “House Speaker Mike Johnson is pushing toward action this week on aid for Israel, Ukraine, and Taiwan, unveiling an elaborate plan Monday to break the package into separate votes to squeeze through the House’s political divides on foreign policy.”

Politico notes, however, that “it’s far from certain that Johnson would have the votes to bring the bills to the floor, given the procedural hurdles of Republicans’ narrow majority that have vexed the speaker for months.”

Time is short: Ukraine’s top general warned this weekend that his ammo-strapped forces’ battlefield situation has “significantly worsened in recent days.” Happy Tuesday.

‘The World is an Increasingly Dangerous Place’

In the wake of last night’s announcement by Speaker Johnson, it appears there’s a pretty good chance of finally getting Ukraine the aid it so desperately needs. But twists and turns and obstacles remain ahead. Speaker Johnson’s gambit of four separate bills may fail. His promised open-amendment process may stray far enough afield from the Senate’s $95 billion February aid package to throw things back into uncertainty in the upper chamber.

It may yet prove that the only way to actually get aid moving is for 23 House Republicans to step up and sign the discharge petition for the Senate bill—the number of additional signatures needed to get to 218 and force that bill to the House floor.

Great damage has already been done by the unconscionable delay–both on the battlefield in Ukraine, and to U.S. credibility in the world. None of this damage can be reversed quickly. But at least the downward trajectory may have been halted for now.

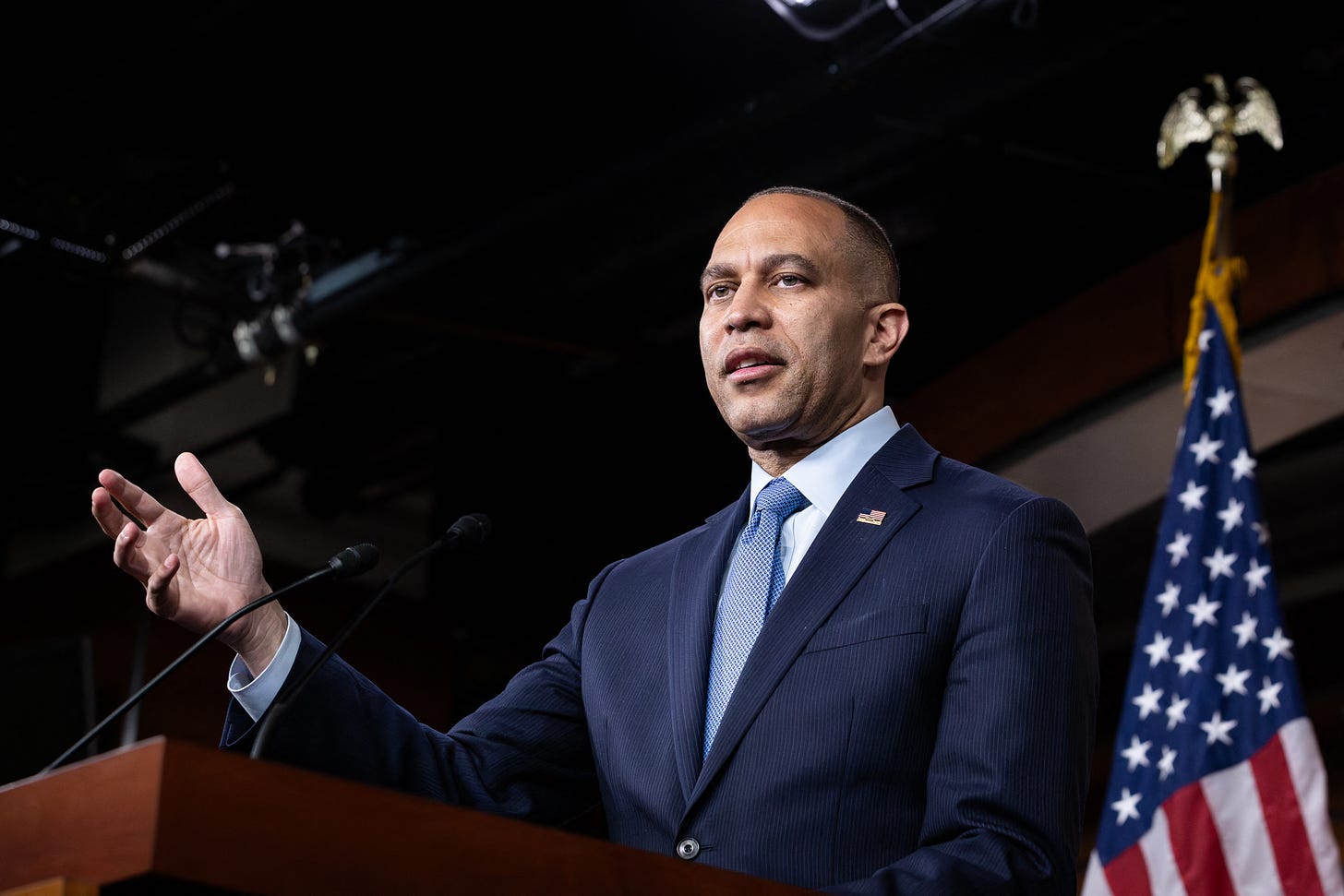

There’s an interesting sentence in yesterday’s letter from House Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries to his colleagues.

It’s a good letter, excoriating Republicans for their failure to move on the national security package and urging them finally to do so. But the sentence that struck me is this: “The world is an increasingly dangerous place and we must continue to stand with our democratic allies in Ukraine and across the globe.”

The second half of this sentence is correct and unobjectionable. But the first half is a striking statement for a leader of the president’s own party to make in a reelection year: “The world is an increasingly dangerous place.”

Presidents usually run for reelection saying that things are better than they were four years ago. President Biden can legitimately make that claim, for example, about the economy. But not about the world.

Now, it is perfectly fair for defenders of the Biden administration to say that most of the reasons the world is an increasingly dangerous place aren’t Joe Biden’s fault. Some are simply beyond U.S. control. Some are due to failures of preceding U.S. administrations. Indeed I think it’s true that other administrations of the 21st century have more to answer for than does President Biden’s. Failures of Presidents Bush, Obama and Trump—very different kinds of failures, for very different reasons—laid the groundwork for the current moment.

Still: If this is an increasingly dangerous world, it means that in this respect President Biden can’t run a typical incumbent reelection campaign. He can’t simply say, “Things are getting better! The world is safer than it was four years ago.”

President Biden will instead have to run as someone who’s been coming to grips with a new and dangerous situation. He’ll even have to acknowledge that to some degree he hasn’t yet been able to turn the situation around—though he is committed to doing so.

Candidate Biden will have to sound like FDR in 1940 or Harry Truman in 1948, not like Bill Clinton in 1996 or Barack Obama in 2012:

“Things were going in the wrong direction in the world, and in some respects they still are—but I am willing and able to deal with these dangers, and my opponent most certainly is not.”

This is a more complicated and challenging electoral message than a typical “Morning in America” reelection campaign. But it’s the message Joe Biden will have to deliver this year. And it does have the advantage of being true.

—William Kristol

How did Israel and its allies manage to thwart Iran’s weekend drone-and-missile attack so successfully? Bulwark Military Affairs Fellow Will Selber has some thoughts:

When Bureaucracy Matters

Israel might not have been as successful at thwarting Iran’s direct attack without a little-noticed bureaucratic reshuffling nearly three years ago.

On 1 September 2021, United States Central Command (CENTCOM), a key player among the eleven combatant commands inside the Department of Defense, made a significant announcement: They would assume responsibility for U.S. forces in Israel. The move would have far-reaching implications. Despite the small number of US forces in Israel, primarily stationed within the U.S. Embassy, this decision placed Israel inside the Area of Responsibility (AOR) of an entity with almost two decades of warfighting experience across North Africa, the Middle East, and Central and South Asia.

Previously, Israel had been housed under the DoD’s European Command (EUCOM), partly because America’s Arab partners did not maintain diplomatic relations with the world’s only Jewish State. However, the Abraham Accords helped usher in a new regional paradigm. With relations with the Sunni Arab world thawing, it made more sense both diplomatically and practically to finally move Israel into a command alongside its foes and allies alike.

When I served at CENTCOM Headquarters from 2009 to 2012—affectionately known as SADCOM due to its grueling work pace—coordinating with our Israeli partners was always more difficult because they fell under EUCOM’s AOR. That added layer of bureaucracy impeded the coordination of sensitive intelligence. More importantly, it made coordinating combat operations more burdensome. Any plans had to be routed through EUCOM for concurrence, which wasn’t always easy.

The results of that September 2021 move were on full display last weekend, as Israel and its allies put on quite a performance. While Israel’s integrated air defense system deserves the majority of the praise, CENTCOM’s role in coordinating this defense was also impressive, specifically the Air Force Central Command’s Combined Air Operations Center, which “provides command and control of airpower” throughout CENTCOM’s AOR. In short, they ensured that Israel, the United States, the United Kingdom, France and Jordan destroyed 99 percent of Iran’s 300 drones and missiles. That’s an incredible accomplishment, considering those attacks emanated from Iran, Syria, Yemen, and Iraq.

If Israel had stayed inside EUCOM, that impressive combined air defense operation might have been less successful. EUCOM and its CAOC have their hands full in Ukraine and battling Russian malfeasance elsewhere. Juggling two conflicts at once might have been overwhelming for a command without a similar deep reservoir of warfighting experience.

While Israel contemplates its response, it will be supported by a combatant command very familiar with Iran and their proxies. They have been fighting them in the shadows for decades in Iraq and Afghanistan. More importantly, CENTCOM’s 40,000 service members and contractors in Iraq, Syria, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, Jordan, and Qatar stand ready to provide President Biden with options no matter how this war plays out in the coming weeks and months ahead.

—Will Selber

Catching up . . .

Supreme Court to hear obstruction case that could bar some charges against Trump: New York Times

In first day of trial, legal wrangling over Trump’s tabloid lifestyle: Washington Post

Arizona GOP strategy document implores party to show ‘Republicans have a plan’ on abortion: NBC News

Number of homicides plunges in major cities after pandemic-era surge: Axios

China is funding the U.S. fentanyl crisis, House panel says in new report: NBC News

Quick Hits

1. ‘The Risk of Unfair Prejudice Is Through the Roof’

A big challenge with putting a guy like Trump on trial: extricating the unsavory stuff he’s actually standing trial for at any given moment from the soup of unsavory stuff that’s made up the bulk of his private life. Per WaPo:

In a case so closely tied to an alleged sexual liason, lawyers spent much of Monday arguing over what a jury can be told about other purported indiscretions in Trump’s life. Prosecutors wanted to tell the jury that he also had an affair with Karen McDougal, a Playboy model, at a time when his wife, Melania Trump, was pregnant with his child.

[Trump lawyer Todd] Blanche argued that would poison the jury against his client, for something that was not a crime and has no bearing on the charges he is facing.

“The risk of unfair prejudice is through the roof,” Blanche said, “from salacious details about a completely different situation.”

Prosecutor Joshua Steinglass argued that the details of the McDougal affair were important to show Trump’s state of mind and behavior when allegations of sexual impropriety surfaced against him.

The judge said the jury could be told about the affair, but not the additional detail that at the time Melania Trump was pregnant. That detail, he said, was prejudicial, although he reserved the right to change his thinking on that matter as other evidence is introduced during the trial.

Jury selection continues today, and is expected to take quite a while.

2. ‘Welcome to Pricing Hell’

Reading what economists have to say about pricing is usually sort of an ‘eat-your-brussels-sprouts’-type exercise, but Christopher Beam’s first piece in The Atlantic is a fascinating exception. From add-on fees to personalized pricing, he writes, what a given thing costs is getting more ambiguous by the day, especially online—a development economists seem to love and everybody else tends to hate:

In a classic 1986 study, researchers posed the following hypothetical to a random sample of people: “A hardware store has been selling snow shovels for $15. The morning after a large snowstorm, the store raises the price to $20.” Eighty-two percent said this would be unfair.

Compare that with a 2012 poll that asked a group of leading economists about a proposed Connecticut law that would prohibit charging “unconscionably excessive” prices during a “severe weather event emergency.” Only three out of 32 economists said the law should pass. Much more typical was the response of MIT’s David Autor, who wrote, “It’s generally efficient to use the price mechanism to allocate scarce goods, e.g., umbrellas on a rainy day. Banning this is unwise.”

The gap between economists and normies on this issue is huge. To regular people, raising the price of something precisely when we need it the most is the definition of predatory behavior. To an economist, it is the height of rationality: a signal to the market to produce more of the good or service, and a way to ensure that whoever needs it the most can pay to get it. Jean-Pierre Dubé, a professor of marketing at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business, told me the public reaction to the Wendy’s announcement amounted to “hysteria,” and that most people would support dynamic pricing if only they understood it. “It’s so obvious,” he said: If Wendy’s has the option to raise their prices when demand is high, then customers can also benefit from lower prices when demand is low.

Economists think about this situation in terms of rationing. You can ration a scarce resource in one of two ways: by price or by time. Rationing by time—that is, first come, first served—means long lines during periods of high demand, which inconvenience everyone. Economists prefer rationing by price: Whoever is willing to pay more during peak hours gets access to the product. According to Dubé, that can benefit rich people, but it can also benefit people with greater need, like someone taking an Uber to the hospital. You can find academic studies concluding that Uber’s surge pricing actually leaves consumers better off.

When you think about it, though, dynamic pricing is a pretty crude way to match supply and demand. What you really want is to know exactly how much each customer is willing to pay, and then charge them that—which is why personalized pricing is the holy grail of modern revenue management. To an economist, “perfect price discrimination,” which means charging everyone exactly what they’re willing to pay, maximizes total surplus, the economist’s measure of goodness. In a world of perfect price discrimination, everyone is spending the most money, and selling the most stuff, of all possible worlds. It just so happens that under those conditions, the entirety of the surplus goes to the company.

Cheap Shots

Hey, we get it—court proceedings can get a little boring:

Just like our loss in Vietnam changed how the US was perceived, the failure to support Ukraine is already an accomplished fact. So even if aid is passed. weaker nations will know not to believe US promises.

We in the US often think of governments that don't function and imagine that we do it better. And if the matter is controlled by govt agencies, then we do do it better. Thus our defense department, post office, Park Service all deliver the goods. But our policy arm - Congress - is an utter failure. A parody of democracy dominated by legislators who are performance artists rather than the successors of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster.

"a way to ensure that whoever needs it the most can pay to get it."

Unless they're poor, in which case it means they get the adventure of figuring out how to live without the resource. Inconvenient if we're taking about umbrellas. Outrage -inducing if we're taking about cancer drugs.

"If Wendy’s has the option to raise their prices when demand is high, then customers can also benefit from lower prices when demand is low."

See, they talk about how the general public is ignorant and it's driving their opposition to policies that would make their life better, and then they say stuff that makes it clear that they left stuff like human psychology and empirical reality behind long ago. People are against surge pricing because they know there's *zero* chance it ends with lower prices when demand is low. It ends with current prices when demand is low, and higher prices when demand goes up. Nobody anywhere is going to leave that situation thinking they came out ahead.