Aquilino Gonell, American Hero

How a Dominican immigrant and military veteran risked his life to protect the U.S. Capitol, then found the courage to talk about it.

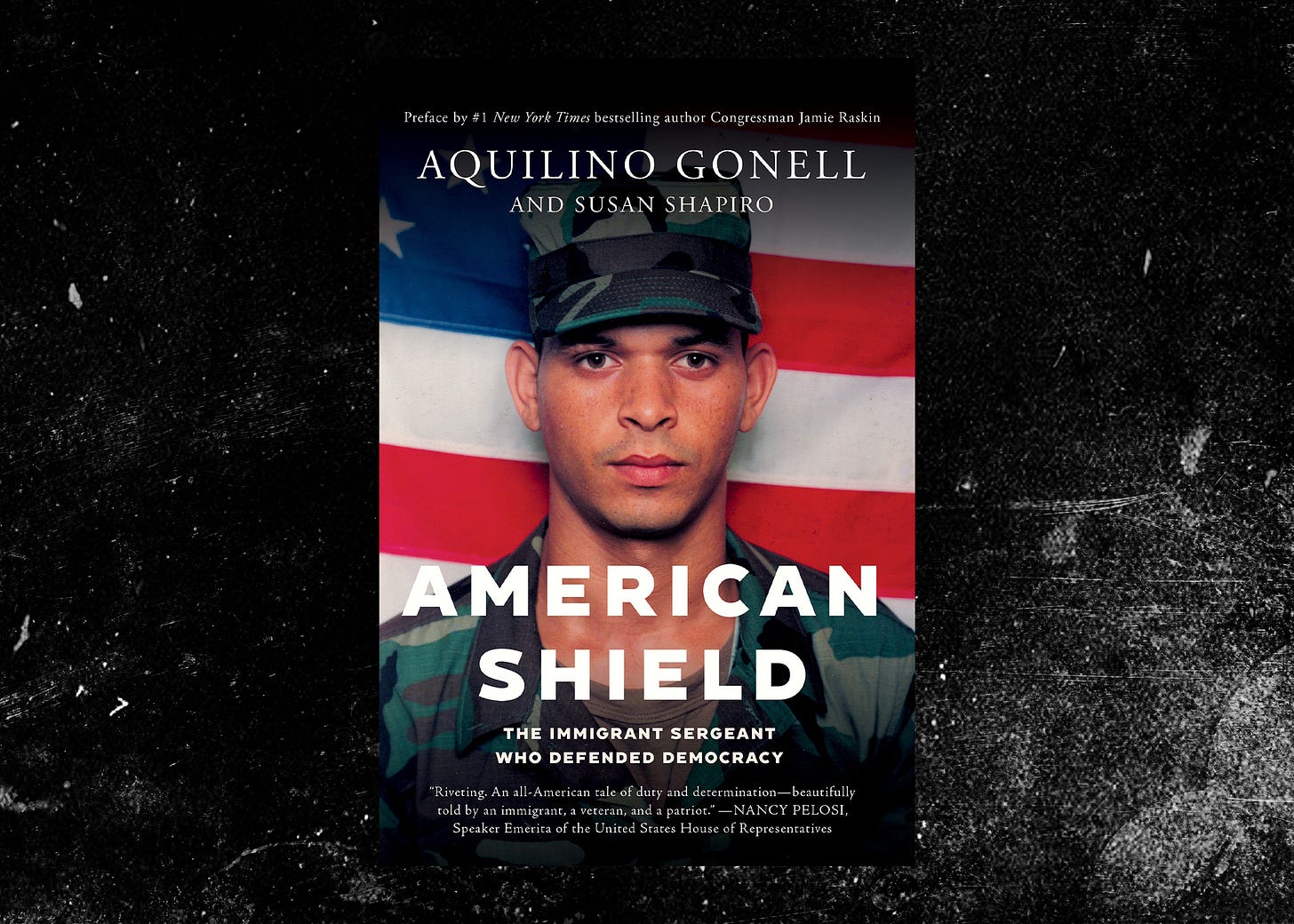

American Shield

The Immigrant Sergeant Who Defended Democracy

by Aquilino Gonell and Susan Shapiro

Counterpoint, 240 pp., $28

AQUILINO GONELL HELD HIS TONGUE as long as he could. He had been among the more than 400 Capitol Police officers on duty on January 6, 2021, as a mob instigated by President Donald Trump attacked the U.S. Capitol. He saw his fellow officers being “brazenly beaten with pipes, sticks, and rocks by rioters chanting ‘Fight for Trump’ and ‘USA! USA!’” He was there as they “hurled bear sprays and full cans of soda at us, making pipes and a giant Trump banner with a metal frame into ramming devices, weakening our queue.”

Gonell, an immigrant from the Dominican Republic, had joined the Capitol force in 2006 after a stint in the Army Reserves that included a year of active duty in Iraq. As he tells in his new book, American Shield, he engaged in hours of hand-to-hand combat with the January 6th rioters, mostly in an underground tunnel where he had once guarded George W. Bush and Barack Obama as they walked to their inaugurations. (At one point during the melee, Gonell was momentarily relieved by Michael Fanone, an officer with Washington’s Metropolitan Police Department, who would later be badly beaten as members of the mob shouted “Get his gun!” and “Kill him with his own gun!”) Gonell, in his book, describes what he witnessed on January 6th as “worse than Iraq.”

Sgt. Gonell was at the Capitol until after 3:41 a.m. the next morning, when Biden’s election was finally certified. He learned that a Capitol Police colleague, Officer Brian Sicknick, was taken to the hospital after collapsing in the Capitol (he died in the hospital the next day), while Republican Senators Ted Cruz and Josh Hawley persisted in seeking to block the certification of electoral votes. “Even after the attacks, they were still echoing President Trump’s false claims that the election he lost was stolen,” Gonell writes. He remembers saying at the time, “I can’t believe this horror show.”

The injuries Gonell sustained would require months of painful rehab and surgery. It reactivated his PTSD from Iraq, caused some permanent disability, and ultimately ended his sixteen-year career with the Capitol cops. His last day on full duty was on January 20, 2021, when he provided security for the inauguration of President Joe Biden. That March, while remaining a member of the police force, he had to turn in his service weapon because he “missed the deadline” for a weapon certification he knew he wouldn’t pass, due to his injuries. The first thing he did was buy a personal handgun to replace it, should it be needed to defend his family.

That’s what Gonell was weighing in his mind, the reason he was holding his tongue. As Trump and his allies spread lies about the insurrection, he wanted to speak out about the events of that day. But Gonell and his wife, Monica, were rightfully worried about the danger this would pose to their family. As he writes in American Shield, “Trump was famous for publicly attacking anyone who went against him. This was a guy who’d encouraged his mob of insurrectionists to hang his loyal vice president. What would he do to us?”

Gonell would get into arguments with family members who said things like “But there were irregularities in the voting,” or “There’s a lot of news reports saying the protests were started by Black Lives Matter and Antifa.” “Look, that’s bullshit,” he responded angrily. “I was there, on the front lines! I did not see one Black Lives Matter or Antifa protester there. They were all Trump supporters, armed, in MAGA hats. And I didn’t watch it on TV or read about it on the internet.”

But still, even after other officers, including Fanone and Harry Dunn, began publicly speaking out, Gonell kept his mouth shut. It was eating him alive. What finally pushed him over the edge was watching the Republicans talking on the telly: “Glued to the news, I was sickened to hear Republican leaders Lindsey Graham, Jim Jordan, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Josh Hawley, and Donald Trump peddling the ongoing deception that the insurrection was a peaceful protest.” Worse, some members of Congress, including people he knew and had protected, “refused to blame our lawless ex-president for causing this historic tragedy.”

Gonell couldn’t stand it anymore. He reached out to his friend Dunn. The next thing you know, he was on national TV.

GONELL’S FIRST-EVER TELEVISION INTERVIEW aired on CNN on June 4, 2021. He tried to convey the fury he and others faced. “They called us traitors. They beat us. They dragged us,” he told reporter Whitney Wild. “I could hear the rioters scream ‘We’re going to shoot you. We’re going to kill you. You’re choosing your paycheck over the country. You’re a disgrace. You’re a traitor.’”

Gonell would go on to make appearances on ABC, Telemundo, Univision, and NPR, and be quoted in major newspapers. He testified before the House January 6th Committee. At one point during his testimony, he teared up. Fox News hosts mocked him for it; he angrily points out that one of these hosts had made a hero out of Kyle Rittenhouse, the 17-year-old vigilante who shot and killed two people at a Black Lives Matter protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin, “then sobbed in court to get leniency.” In Gonell’s case, he didn’t kill anyone, even though, he points out, “unlike Rittenhouse, we had provocation and full authority to intervene.”

There are other books that give inside perspectives into the events of January 6th, including Fanone’s Hold the Line, released last year, and Dunn’s Standing My Ground, out just last month. But what makes Gonell’s story unique is that it is told by an immigrant—someone who chose to come to this country and become a citizen, and who felt personally responsible for defending the institutions of American democracy. He writes at one point: “As an immigrant, I took seriously my pledge to defend and protect the Constitution of the United States against foreign and domestic threats. Even if that threat was the president . . . and the members of Congress who abetted him.”

Gonell was 12 years old when he moved with his mother and brother from the Dominican Republic to Brooklyn to reunite with his father, a taxicab driver. Soon after he arrived, his father was stabbed, for the first of two times. His mother was later seriously burned in a restaurant accident.

In school, Gonell was made fun of for his thick accent, but he found teachers willing to help him learn a new language. He recalls being taught how to pronounce the word “patriot.” “Say it again, until you get it right,” his teacher instructed. He did.

Aquilino’s family life was complicated. His father, it turned out, had managed to create a whole other family in New York; he was a hard man, always working and apt to be verbally abusive. Democratic Rep. Jamie Raskin, in his preface to the book, says Gonell and Trump shared something in common in having “a mean son-of-a-bitch as a father”—the difference being that Donald came to emulate his bad dad while Aquilino rebelled against his own.

Gonell grew up in constant fear of doing something that would get his family deported. He worked jobs from when he was 14 on to help out his family. At 16, he traveled back to the Dominican Republic, intending to stay, only to be persuaded to return. “There’s nothing for you here,” his grandfather told him. In 1996, on a class trip to Washington, D.C., he visited the U.S. Capitol, where he interacted with a Capitol cop. He remembers thinking: “It must have been a perilous job to work here, protecting the senators and congressmen milling around with everyday visitors. Knowing there was an armed guard here made me feel safer.”

One day, as he was nearing adulthood, Gonell learned that his father had berated his mother in full view of customers at a pizzeria they had come to acquire. As he tells it:

I rushed to the pizza place, barged in, and confronted my father in front of a full restaurant. “How could you talk down to Mom like that?” I yelled. “What kind of man are you, to disrespect your wife at work in front of everybody? You should be ashamed of yourself!”

It was the kind of uncommon courage that Gonell has been able to tap into all of his life. It’s why he deserves to be seen as a national hero.

GONELL ENLISTED IN THE ARMY RESERVES in 1999 in order to afford a college education. Being in the military also made it easier for him to become a naturalized U.S. citizen, which he did in November 2001, shortly after the 9/ll attacks. He was promoted up the ranks from private to private two, to private first class, to specialist, and eventually to sergeant. In 2004, he was told to pack his bags for Iraq. One day, he walked into a PX store on base to buy candy just as the people just behind him in line were hit by mortars fired by Iraqi insurgents. Three GIs who had been slated to go home the next day were killed. One of them, whom Gonell had just spoken to, was decapitated.

Gonell tells this story in a chapter headlined, “Everywhere Was Front Lines.” Besides the constant danger, he says he was bullied by an officer who slightly outranked him. But he was not afraid, in his own role as a supervisor, to lay down the law. When a soldier under his command gave a bottle of what turned out to be urine to a boy who had asked for a Gatorade, and referred to the lad using a slur for Arab, Gonell wrote him up and chewed him out.

“Demeaning people in their own country, you’re going to inflame the situation, make Iraqis hate us even more than they already do and take revenge. You can get someone killed,” Gonell shouted. “How would you feel to be called a cracker, redneck, or white trash, you fool? If I hear any slurs or mistreatment again, I’ll report your ass and recommend harsh disciplinary action.”

Gonell at times conveys disaffection for the military, describing his clashes over a bonus that was promised but never delivered and the denial of benefits from the VA. He disagreed with the U.S. decision to invade Iraq in 2003, but was nonetheless deployed there in 2004. That year, from Iraq, he cast his first-ever ballot for president—against G.W. Bush. His job with the Capitol Police appears to have been a better fit. He became personally acquainted with Sen. Joe Biden and other lawmakers. He liked protecting this magnificent building.

In 2020, during the height of protests against the police killing of George Floyd, a black protester shouted to his face that he was “a pig and a killer.” Gonell says he replied:

What if I called you a thug or gangster, stereotyping you based on your looks, clothes, or skin color? . . . That’s what you did to me. You don’t know me or my background. If I were there, I would have jumped on [Minnesota police officer Derek] Chauvin to stop him from hurting George Floyd.

Gonell, in his book, notes the discrepancy between the insufficient law enforcement presence at the Capitol on January 6th and a Black Lives Matter protest he was at about six months earlier, when there were “thousands of uniformed policemen on site with loaded weapons ready to use.” He recalls how Trump, after giving his incendiary speech and turning his mob loose to attack the Capitol, refused for hours to intervene or even call out the National Guard.

“Trump wasn’t shutting down this dangerous free-for-all because he wanted it. They were doing this on his behalf,” he realized. Others “abetted the mob” by failing to send reinforcements. “Because of that bootlicking and flagrant dereliction of duty, my troops were exposed, vulnerable, and out in the cold. We were abandoned.”

Gonell, now 44, did not officially leave the Capitol Police until December 2022, after his retirement with disability was approved, putting him among the 20 percent of Capitol Police officers who left as a direct result of the January 6th riots. After his media appearances brought him a modicum of recognition, Gonell finagled a chat with General Mark Milley, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, to thank him for testimony he had just given that was critical of Trump. He says the general praised him in return.

Others reacted differently, as Gonell relates: “When I bumped into Ted Cruz, Josh Hawley, and Lindsey Graham in the hallways and elevators at the Capitol, they cravenly pretended not to see me, not acknowledging that I’d put my life on the line to protect theirs.”

Things have only gotten worse as Trump and much of his party have taken to celebrating the mob violence he unleashed on January 6th. Just last week, at a rally in Houston, the former president and probable 2024 Republican nominee played a song recorded by men jailed for their actions on January 6th, telling his rapt audience, “I call them the J6 ‘hostages,’ not ‘prisoners.’”

Yet courage finds its own rewards. In August 2021, at a White House ceremony, Gonell got to shake hands with President Biden:

During the ceremony he watched his young son, wearing the same khakis-and-vest outfit as his dad, looking up at him “starry-eyed, tapping my shoulder and whispering, ‘I’m proud of you’ in English, then a bit later he said it in Spanish too. “Estoy orgulloso de ti, papi.”

There are, as we are constantly reminded, lots of cowards in Congress. The people who guard them are not.