Arnold Schwarzenegger Is No Hero

His recent authorized documentary tells a sanitized story. To learn the truth about this catch-and-kill pioneer, you’ll need to revisit some tabloids from 2001.

A SERIAL OFFENDER WITH ALLEGATIONS spanning decades—from sexual harassment to assault, extramarital affairs, and even out-of-wedlock children.

A screen star who became a powerful Republican politician.

And a network all too eager to run an airbrushed infomercial on his behalf.

All this could describe Donald Trump, of course, with last month’s CNN town hall morphing into an hourlong campaign ad, notwithstanding anchor Kaitlan Collins’s attempts to fact-check him.

But it also describes Arnold Schwarzenegger, the former bodybuilder, action star, and California governor who succeeded Trump as host on The Apprentice. Schwarzenegger hasn’t done a CNN town hall, but he collaborated on (and authorized) a three-part documentary about himself that was released on Netflix this month. His longtime confidant and attorney, Paul Wachter, is credited as an executive producer.

For all their political differences nowadays—with Trump leading the MAGA movement and inciting a riot at the Capitol, and with Schwarzenegger opposing MAGA and the riot—the two men share a singular political distinction: both achieved their political goals and eluded much humiliation with the help of “catch-and-kill” accords with American tabloids. It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that Schwarzenegger pioneered the master catch-and-kill methodology with tabloid czar David Pecker that Trump would later use to clear his path to the White House.

FOR THOSE WHO AREN’T ALREADY FAMILIAR with Schwarzenegger’s history, some of the people from his past you likely won’t know much about include:

The dozen-plus female accusers cited in the national media’s coverage, most notably the Los Angeles Times’s 2003 reporting on the women who accused the former Mr. Olympia of sexual abuse (eventually at least 15 would come forward to the paper).

The stuntwoman Rhonda Miller, who in 2004 sued the bodybuilder and Hollywood star over two alleged instances of sexual assault and defamation (Miller lost the suit and settled).

Mildred Baena, the housekeeper Schwarzenegger impregnated during an affair in the Brentwood family home he shared with wife, Maria Shriver; the two women gave birth in 1997 within days of each other. (While Shriver claims not to have learned of the affair or Baena’s son until near the end of her husband’s tenure as governor, Schwarzenegger’s “love child” was widely rumored for years in the film industry, his identity whispered about among office and family staffers.)

Media whistleblower B.J. Rack, a co-producer/coordinator on Schwarzenegger’s films who described to me in discomfiting detail what had been an open secret in Hollywood: years of sexual harassment on his film sets. (“I smacked him in the face,” she told me, recounting just one incident. “Just smacked him and he dropped me. And I said, ‘Never, ever touch me again.’”)

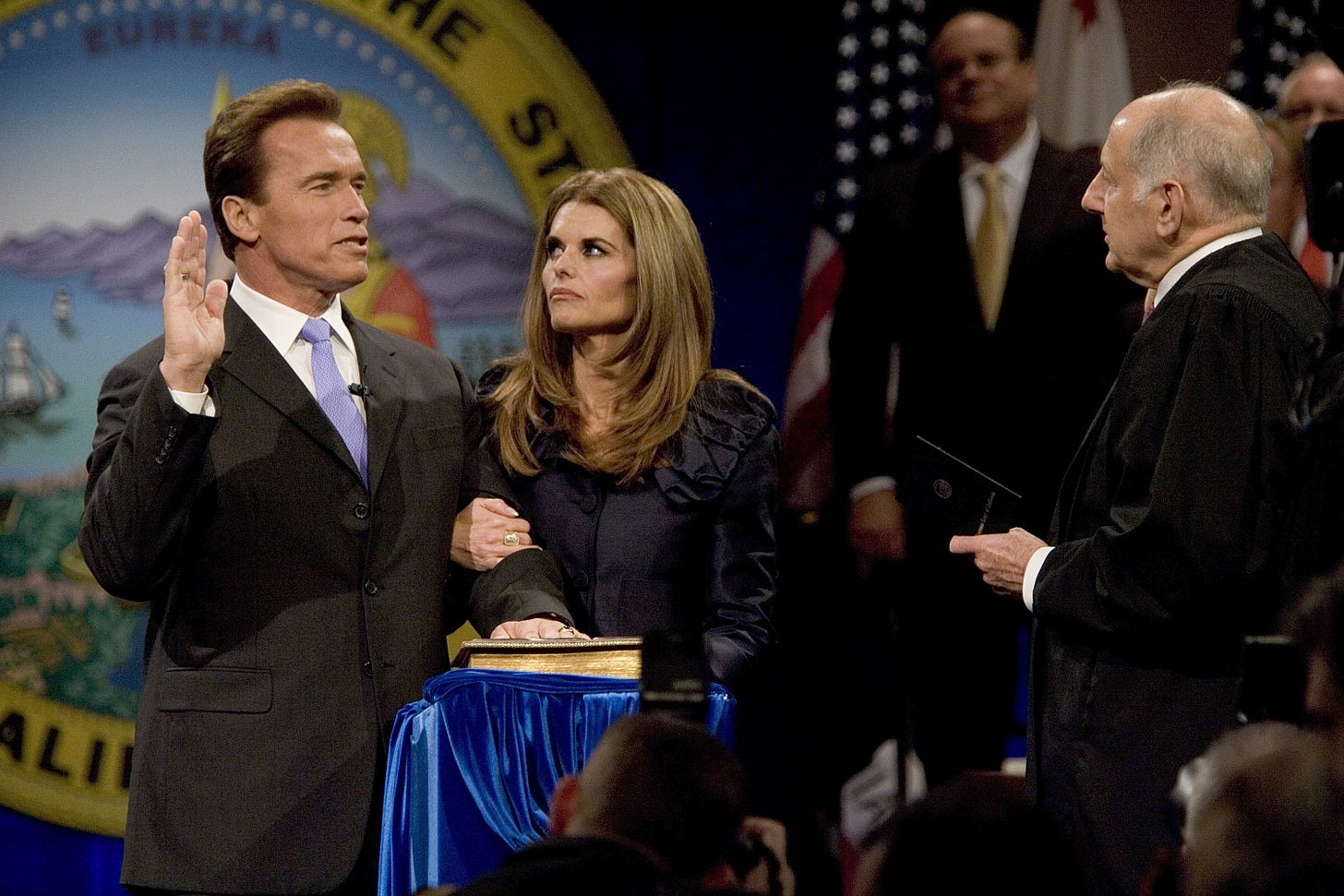

Much of this was known or reported in the early 2000s, right when Schwarzenegger was making his move into politics, culminating in his campaign for governor during the 2003 recall of Governor Gray Davis. And certainly, Shriver played a crucial role in enabling her husband’s political aspirations. “You can listen to people who have never met Arnold or who met him for five seconds 30 years ago,” Shriver famously said, challenging his accusers days before the election, “or you can listen to me. I advise you to listen to me.” Schwarzenegger went on to win the governorship by a 17-point margin.

But the key to his success wasn’t ultimately Shriver, invaluable as her support was at the time. Nor was it the phalanx of aggressive lawyers and media fixers who publicly battled negative press on his behalf. Schwarzenegger’s real secret was that he had a kingmaker on his side—someone who was able to keep unsavory stories about him out of the public view in the first place. That person was David Pecker, the CEO of American Media Inc. (AMI).

THESE DAYS, PECKER CAN OFTEN BE FOUND in the company of federal prosecutors intent on learning every nuance of his catch-and-kill arrangements with Donald Trump. He also appeared before the New York grand jury that indicted Trump for illegally hiding hush money payments to the adult-film actress Stormy Daniels and Playboy model Karen McDougal. Such sordid business is Pecker’s stock-in-trade: He knew just what to do when Trump knocked at his door. That’s in part because he performed a successful trial run employing catch-and-kills on behalf of Schwarzenegger over a decade before Trump’s 2016 presidential run. The playbook had been written and executed to perfection.

Consider the damage the Daniels and McDougal stories would have inflicted on Trump’s campaign if they had become public in the wake of the Access Hollywood tape scandal. Indeed, one could reasonably argue that without Pecker’s previous article-killing collaboration with Schwarzenegger, which established a proven template, there may have been no Trump presidency.

There was not a happier soul at the inaugural galas for both Schwarzenegger and Trump than the diminutive Pecker, bedecked in a smart, tailored tux and glowing with pride.

In 2004, I interviewed Pecker at length—as well as dozens in his and Schwarzenegger’s employ. Beaming, he described to me how Arnold became his “business partner.” That unseemly partnership had begun when Schwarzenegger and his associates began negotiations in 2002 to sell their Weider bodybuilding supplement company and magazine titles to AMI. Schwarzenegger’s importance as a spokesperson for Weider products was as significant as his stake in the company.

For Pecker, the deal lifted AMI’s fortunes at a time when its tabloid sales were dipping. In exchange, his empire of “tabs” became “an Arnold-free zone.” The relentless drip of damaging stories of the Terminator’s extramarital flings, which had been routine fare in supermarket checkout lanes for years, simply ceased.

Some national media soldiered on and did some high-impact reporting after the AMI pipeline of muck dried up. (Because tabloids often paid their sources, a disreputable practice in the mainstream media, they were able to break hard-to-get stories that established publications would later follow up with their own reporting.) But those covering the gubernatorial race didn’t catch everything. At the very least, one major story about Schwarzenegger that would have affected his electoral prospects was, in the now-familiar industry parlance, “caught and killed” soon after he announced his gubernatorial campaign.

BEFORE WE GET TO THAT, what kind of stories had the tabloids been running about Schwarzenegger? A good example is the National Enquirer February 2001 “Arnold Exclusive,” which carried the headline, “He’s Caught Cheating.” A pull quote from the article gives the general tenor of the type of coverage Schwarzenegger had been receiving: “Arnold has the worst reputation in Hollywood for groping, grabbing and lewd remarks!”

Two months after the cheating story, the Enquirer announced a “World Exclusive.” The cover story, headlined “Arnold’s Shocking 7 Year Affair,” chronicled his alleged dalliance with a former child actress named Gigi Goyette, accompanied by photos of Goyette, a minor, in a thong bikini posing with Schwarzenegger. Just before these Enquirer stories came out, Premiere magazine had published a scathing exposé of Arnold’s brutish, sexual behavior on film sets; that story ran alongside photos of him groping two different female interviewers. It appeared to be a lethal blow for any candidate, but especially one running under the banner of the then family-values-focused GOP.

On May 15, 2001, Pecker’s National Enquirer published a further story, “Arnold’s Dirty Secrets—Why He Can’t Run for Governor,” bragging about how the tabloid had foiled the star’s political ambitions. “Arnold Schwarzenegger terminated his plans to run for governor of California just hours after he found out the Enquirer was publishing a story about his affair with sexy Gigi Goyette,” gushed the Enquirer, “because he didn’t want even more scandals uncovered if he made a bid for public office!” Pecker’s tabloid continued to run reminders of its Arnold takedown for the rest of 2001, updated with salacious tidbits.

Indeed, Schwarzenegger ultimately decided against running for governor in the 2002 election, and his tabloid coverage likely had much to do with his decision. But the action star wasn’t done with politics. The 2003 recall election presented a unique opportunity for him to make his move, but—like Trump years later—he knew he first had to slay his nemesis: the tabloids. That meant Schwarzenegger had to meet with David Pecker and secure a truce. The July 2003 meeting of the two—with the action star accompanied by his close adviser, Paul Wachter—would culminate with the sale of Weider to Pecker’s AMI and the full-stop cessation of hit pieces on the former bodybuilder.

Negotiations for the deal went on between Weider and AMI for more than a year; a confident Schwarzenegger announced his candidacy while they were still ongoing. The final arrangement between him and Pecker was made public only after Arnold won the governorship.

At a press conference in March 2004, Pecker and Schwarzenegger, grinning broadly at each other, announced that Arnold would become the executive editor of AMI’s newly acquired Muscle & Fitness and Flex. Schwarzenegger—while governor—would garner an undisclosed salary plus five annual $250,000 donations to the Governor’s Physical Fitness Council.

The political function of the sale was clear. One senior Enquirer editor lamented that “Arnold neutralized the tabs.” Not only that, but he suddenly had the tabloids championing him.

Two days after Schwarzenegger announced his candidacy for governor, AMI paid Goyette $20,000 to sign a confidentiality agreement about her relationship with the candidate. Though the Enquirer had broken the story of Goyette and Schwarzenegger’s relationship in April 2001, the publication disclosed nothing further about their affair to its readers. The details of her hush-money agreement with AMI would not be revealed until the Los Angeles Times reported it in August 2005, long after Schwarzenegger had assumed the governorship of the nation’s most populous state.

TRUMP AND SCHWARZENEGGER have different styles and swagger, and each uses his own political calculus. The New York real estate tycoon is more crudely brazen than the former bodybuilder, who advocates environmental conservation and now speaks out against antisemitism, even earning some plaudits from liberals for his opposition to Trump.

Yet Arnold and the Donald are equally gifted in the art of deception. They come clean only after getting caught—and even then, not always. Trump still denies knowing E. Jean Carroll, who just bested him in court to the tune of $5 million in damages for sexual assault. (Schwarzenegger was also sued for defaming one of his accusers, who cited two incidents in court papers.) Arnold only admitted his affair and son with his housekeeper after the Los Angeles Times confronted him with irrefutable evidence in 2011.

Before the Times settled the matter once and for all, I directly asked Schwarzenegger at a campaign stop whether the rumors of his “love child” were true. (For a period, reporters were chasing down rumors of multiple “love children.”) He responded with a frozen stare of quiet fury: “Absolutely not,” Schwarzenegger told me.

But for all his history of boorishness, Arnold can be much smoother than Trump. He personally called producer B.J. Rack ahead of the 2003 Los Angeles Times series to coax her into reversing her account to various reporters. “Maria would like you to make a statement,” he began, Rack recounted to me. “Something like, ‘I worked with Arnold for four years or whatever . . . and I never saw any sexual misconduct.’” Rack refused—and held that position until her death.

A few years back, I interviewed two women about their relations with the action star, whom they said they had met when they were teenagers. Both at first seemed determined to break the nondisclosure agreements they had signed as part of their settlements. But at decisive moments, Arnold magically reappeared in their lives: For one, it had been years since he had spoken to her—but now he had invited her to lunch and was offering to help her career. She stayed mum.

As the #MeToo movement blossomed all around them, taking down stars and politicians with far less to hide, Trump and Schwarzenegger have chosen different strategies to survive. Trump lashes out and attacks his accusers. Arnold opts for a lighter, personal touch. He has been savvy enough to rein in his army of lawyers, once renowned for slamming inquiring reporters with threats and cease-and-desist letters. He has started to admit to behavior that for years he denied. In October 2003, after the Los Angeles Times broke the story of the sexual harassment allegations from six women just before the gubernatorial recall election, Schwarzenegger carefully conceded that he had “behaved badly sometimes” on “rowdy movie sets.” But regarding the allegations, he continued, “I would say most of it is not true.” Later, during a 2018 interview to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of Men’s Health, he went a bit further, conceding that he “stepped over the line several times” with women and saying, “I feel bad about it, and I apologize.”

The just-released Netflix documentary has provided Schwarzenegger a tightly controlled environment for image rehabilitation. In its final hour, he gets around to expressing regrets. “Today, I can look at [my mistreatment of women] and kind of say, it doesn’t really matter what time it is. If it’s the Muscle Beach days, or forty years ago, or today, this was wrong. It was bullshit. Forget all the excuses. It was wrong.” As to his affair with his housekeeper that resulted in a child whose paternity he kept secret for as long as he possibly could, Schwarzenegger calls the episode the biggest “fuckup” of his life.

These are strategic disclosures, to be sure, politically and perhaps psychologically necessary for anyone who has undergone as many humiliating revelations as Schwarzenegger has. His eye is on his legacy—a sympathetic rewrite of his past. Yet his widely broadcast disclosures must be cold comfort to those who have signed away their rights, or taken settlements, or who have otherwise lived with the legacy of his previously unacknowledged and injurious behavior. What use to them are his public amends? Rare is the victim who has both the courage and the legal firepower of E. Jean Carroll. But even so, when Schwarzenegger’s carefully staged mea culpas—however opportunistic—are compared with Trump’s absolute denials of wrongdoing or responsibility, they can’t be said to count for nothing.

Both Trump and Schwarzenegger muscled their way onto the political stage brimming with bravado and self-glory. They both crave a return to the limelight of the global stage. Schwarzenegger knows how to cajole, even charm; Trump knows how to channel resentment into a force field.

That said, they have far more in common than either would care to admit.