DHS Disinformation Board: An Unserious Solution to a Serious Problem

However well-intentioned the idea, the botched rollout does not instill confidence or suggest credibility.

Last week, there was a great disturbance on the right, as if thousands of voices suddenly cried out in terror: “It’s Biden’s Ministry of Truth!”

The outcry was occasioned by the April 27 announcement that the Department of Homeland Security was setting up a “Disinformation Governance Board” to counteract the spread of misinformation and disinformation on issues related to border security, public safety, and elections, as well as Russian disinformation about the war in Ukraine. Author, commentator, and “disinformation expert” Nina Jankowicz was tapped to be its head.

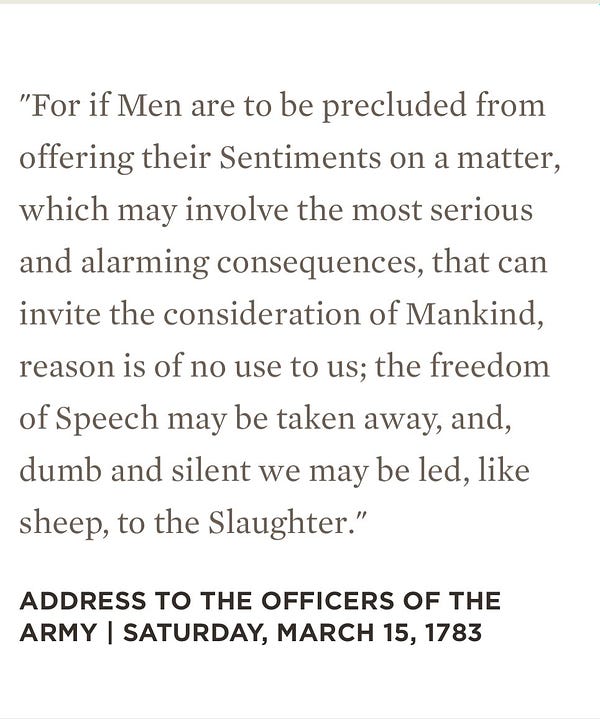

The reaction, which included Tucker Carlson warning of a “new Soviet America” in which the state was about to “get men with guns to tell you to shut up,” was insanely over the top—a mix of ginned-up partisan outrage and genuine paranoid freakout. But that doesn’t mean the board is a good idea, unless it has a narrow and clearly defined mandate, and early press reports give no indication that it does. Its unveiling, at any rate, was definitely a tone-deaf unforced error by the Biden administration.

Some highlights—or lowlights—from the reaction to the announcement:

Several commentators suggested that this initiative was a quick response to tech bad boy Elon Musk’s imminent acquisition of Twitter:

But Jankowicz’s tweet announcing her new post mentions that preparations for the board’s launch had been underway for at least two months—well before Musk’s tarantella with Twitter.

Sanchez’s literary mashup of Ayn Rand and George Orwell at least sort of makes sense. In Candace Owens’s case, she seems to have simply conflated Orwell and J.K. Rowling:

Some lawmakers also took to social media to share their reactions. Here’s Marco Rubio:

Meanwhile, in a letter to Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas, Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Missouri) demanded that the board be “immediately dissolved.” He, too, suggested that the new board was somehow related to Musk’s prospective ownership of Twitter:

Rather than protecting our border or the American homeland, you have chosen to make policing Americans’ speech your priority. . . . While Democrats have for years controlled the public square through their Big Tech allies, Mr. Musk’s acquisition of Twitter has shown just how tenuous that control is. It can only be assumed that the sole purpose of this new Disinformation Governance Board will be to marshal the power of the federal government to censor conservative and dissenting speech.

In fact, for all the posturing about how the DHS was tackling “speech” instead of border security, several reports on the Disinformation Governance Board said that one of the board’s key tasks would be to counter misinformation about border policies spread by human smugglers in order to lure migrants to the U.S.-Mexico border in the hope of receiving asylum. Thus, last September, as the Associated Press noted, misleading messages circulating in Haitian communities on Facebook and WhatsApp contributed to the influx of some 14,000 migrants to the border town of Del Rio, Texas. At the time, Mayorkas expressed concern that “Haitians who are taking the irregular migration path are receiving misinformation that the border is open.”

In one of the more measured, though skeptical, conservative responses to the announcement, National Review’s Jim Geraghty acknowledged that “if this new DHS group spends its time publicly declaring that there are no special, secret, or little-known loopholes for migrants who wish to enter the U.S., it will do some good.” (On the other hand, a remarkably stupid Washington Examiner editorial found a way to explain why even this was a bad thing: You see, under Joe Biden the border really is effectively open, so telling potential migrants it’s not is actually . . . disinformation. Creative!)

Another sober and measured critique came from Matthew Feeney, director of the Cato Institute Project on Emerging Technologies (disclosure: I’m a cultural studies fellow at Cato), who pointed out on Twitter that the board “won’t be an Orwellian Ministry of Truth,” “will be constrained by the First Amendment (i.e. it will not be able to remove legal speech),” and has a relatively narrow mandate “with a focus on election integrity and border security/immigration enforcement.” However, Feeney also cautioned that “the DHS has a history of using surveillance tech and expressing an interest in social media monitoring” (including, during the Trump years, aggressive surveillance of immigrants’ social media use, which somehow failed to alarm the likes of Carlson and Hawley) and that the board’s mandate could expand, as often happens with federal agencies. He also expressed concern that when a unit within the DHS labels certain speech (e.g., claims that “the 2020 election was stolen and the results of the 2022 midterms can’t be trusted”) as equivalent to “Russian disinformation,” it may have a chilling effect:

I have mixed feelings. I think Feeney’s concerns about possible overreach and mission creep are entirely valid. I also think conspiracy theories about election-rigging are self-evidently a threat to our democracy—and are not just disagreement with the government but a demonstrably, factually false belief. However, such beliefs are absolutely protected by the First Amendment. On the other hand, I’m not sure it’s feasible to say that the government should avoid any use of words like “disinformation” or “threat to democracy” because they could make some people feel like their opinions are getting an official seal of disapproval.

Be as it may, I can respect this argument from Feeney, whose concerns are clearly nonpartisan. But a lot of the time, the chilling effects of government rhetoric and action are being lamented by people who saw nothing wrong with targeted surveillance of Muslims during the post-9/11 years or with Trump’s tirades blasting journalists as “enemies of the people.”

There’s also the question of whether official warnings about disinformation are more likely intimidate or to galvanize opposition; I suspect the latter is more likely. (Official warnings from federal institutions like the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control certainly didn’t keep anyone from churning out misinformation on COVID and the vaccines.) Feeney also voices concern that the DHS board could exacerbate “decay in trust in institutions” by “potentially portraying millions of Americans as being indistinguishable from Russian government assets.” That’s a possibility; however, if we’re talking about people who think Joe Biden stole the election in 2020, I’m not sure how their mistrust of institutions could get any worse.

Which brings us to another point: What good will the Disinformation Governance Board actually do, unless it sticks to a very narrow mandate of identifying and rebutting false rumors that don’t easily lend themselves to political spin and don’t involve contested facts? Can such a board scrupulously avoid the appearance (or substance) of partisanship?

The appointment of Nina Jankowicz to the executive director position can give us some clues as to the direction the new board is likely to take. Jankowicz, a 33-year-old Bryn Mawr graduate and “disinformation fellow” at the Woodrow Wilson Center. Predictably, Jankowicz has been the target of some extreme nastiness in the past few days. Even “groomer” innuendo has turned up, after someone unearthed a clip of a song in which Jankowicz supposedly voices erotic fantasies about Harry Potter, a child. (In fact, the song is written from the point of view of another child character from the books—Moaning Myrtle, the ghost—and was recorded when Jankowicz herself was 16.) Jankowicz’s more recent rendition of a “disinformation song” riffing on “Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious” from Mary Poppins was also held up for widespread ridicule and invoked as evidence that she was unfit for a serious job.

Whether you will find Jankowicz’s clip cute or cringeworthy (I think it’s a little bit of both) is a matter of both taste and politics. But it’s largely beside the point.

In some ways, Jankowicz has excellent credentials for the present moment. She is the author of the 2020 book How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict. She has studied in Russia and worked, in 2017, with the foreign ministry of Ukraine. She has also served as supervisor of the Russia and Belarus programs at the National Democratic Institute.

But the accusations of ideological bias, however riddled with partisan bad faith, cannot be brushed aside so easily.

Many of these accusations have focused on Hunter Biden’s laptop, which Jankowicz (then a Wilson Center fellow) dismissed as a “Trump campaign product” in comments to the Associated Press in October 2020. The laptop, now known to be authentic, is a messy subject; but I don’t think anything Jankowicz said is particularly objectionable. She said there were still questions about whether the laptop was really Hunter Biden’s; at that point, there were. (There are still questions about whether some of the contents may have been tampered with.) “Trump campaign product” does not have to mean “fake”; it can mean real material disseminated for propaganda purposes, out of context and with a dishonest spin. (In this case, the dishonest spin is that Biden’s pressure on Ukraine to fire a prosecutor in 2015 was intended to thwart an investigation into Burisma, the gas company where Hunter Biden was then a board member.) It is also worth noting that Jankowicz wasn’t exactly on a crusade to discredit the laptop story; she only made a few comments about it. The worst that can be said is that when Biden made an overstated claim in one of his debates with Trump—that 50 former national security officials and five former CIA heads had concluded the laptop was “a Russian plant”—Jankowicz livetweeted it without pointing out, as CNN did, that the claim was at least somewhat misleading: The officials had said that the laptop saga had “all the classic earmarks of a Russian information operation,” but also stressed that they had no evidence Russia was involved, let alone that the material was planted.

One can parse other Jankowicz comments, op-eds and quotes for either good or bad signs. The bottom line, though, is that she is without a doubt deeply immersed in the culture of progressive social activism and tends to accept its narratives as fact. The strongest evidence of this tendency can be found in Jankowicz’s just-published book, How to Be a Woman Online: Surviving Abuse and Harassment, and How to Fight Back. Not only does Jankowicz fail to mention data (from the Pew Research Center, for example) which contradict the popular view that online abuse overwhelmingly victimizes women, but her account leaves out forms of harassment that don’t fit the progressive paradigm, such as online mobs that turn “callouts” of alleged racism or other bigotries into sadistic public bullying. What’s more, even a quick scan of the book turned up at least one instance in which Jankowicz leaves out some crucial context out of her account of an incident: she writes that feminist software developer Adria Richards was vilified online and eventually lost her job after she “shamed two male attendees at a developer’s conference” for sharing a juvenile joke about “big dongles” (a term for a USB drive that just happens to sound like an off-color slang word) while sitting behind her during a panel. In fact, the backlash against Richards was due to the fact that the man who made the joke was fired from his job despite apologizing.

Can Jankowicz be counted on to be impartial in approaching disinformation when it’s up for interpretation? I would have to say no. And that’s a problem, especially if, as some observers have suggested might happen, the board’s labeling of certain speech as disinformation results in its being removed or otherwise flagged by the social media giants.

Countering disinformation at a time when liberal democracy is under assault from all kinds of bad actors is a crucial task that I think some critics of the board dismiss too lightly. Politico’s Jack Shafer, for instance, points out that our democracy survived decades of Soviet disinformation ops, including the canard that portrayed AIDS as the product of an American bioweapons experiment, “without a Disinformation Governance Board to guide us.” True enough, although there was a considerable Cold War apparatus dedicated to spreading American information and pushing back—certainly abroad, and in ways that sometimes seeped back to domestic audiences—against Communist propaganda. This apparatus included the United States Information Agency and the various CIA-backed literary magazines and other intellectual projects.

Of course, American public trust in government during the Cold War was vastly higher than it is now—even among Americans in whose eyes the wrong party was in charge at the White House. This level of trust was both for the better and for the worse (the CIA got away with some very troubling stuff). In any case, it is unlikely to be rebuilt any time soon.

Under current circumstances, an anti-disinformation center run by the federal government could still work. But it would have to be strictly apolitical in a “just the facts, ma’am” way. If such a unit is run by DHS, for instance, it should limit itself to clearcut disinformation relevant to border issues and counterterrorism. Initial press reports were not entirely clear about the board’s purview; for the board to work well, its functions would have to be narrow and well-defined. In that sense, the Biden administration has certainly botched the rollout of this initiative—especially since, when press secretary Jen Psaki was asked about the board at the April 28 press briefing, she knew nothing about either the board or Jankowicz.

It would also need a less pompous name—one that doesn’t imply there will be some sort of “governance” with regard to disinformation. (What’s wrong with “Counter-Disinformation Center”?)

Obviously, nothing would have appeased the right-wing outrage machine looking for red meat. But the new board also managed to alienate reasonable people like Shafer and Brookings Institution fellow Shadi Hamid:

Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas—who is scheduled to testify before the Senate on Wednesday, May 4—said on Fox News Sunday that the Biden administration, himself included, “could have done a better job in communicating what [the board] does.” He also said that he expects Jankowicz to be objective, and he categorically stated that the board will not engage in policing Americans’ speech.

So far, so good. But for those promises to mean something, the watchers will have to be watched.