Despairing Dems Say Biden and Harris Played It Too Safe

Top operatives say the party needs to break out of its media bubble, not just build a new one.

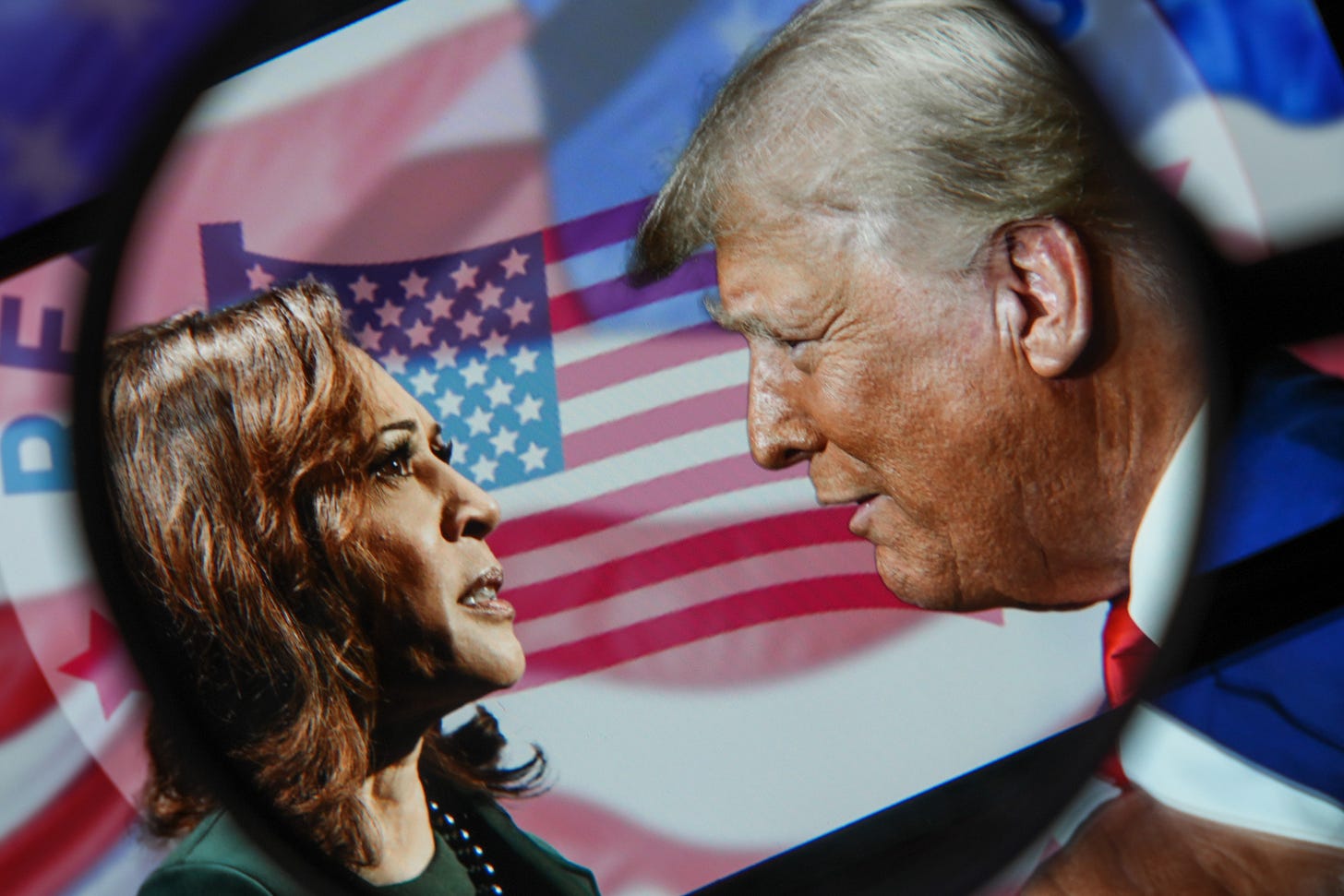

THERE HAS BEEN NO SHORTAGE of recriminations and postmortems in the roughly 48 hours since Kamala Harris lost the election to Donald Trump.

But one thing virtually every Democrat seems to agree on is that the party dramatically hurt itself by not engaging conservative-friendly and alternative media.

In conversations with a number of top Democratic operatives both in and around the campaign, two bleak conclusions emerged. The first is that the party essentially failed to communicate with a huge swath of the electorate by not meeting them where they are. The second is that absent that direct engagement, Democrats allowed rumors, caricatures, and unfair or misleading attacks on their candidates—Harris and Joe Biden, primarily—to define the ticket.

“One thing we saw was people didn’t have an opinion of Kamala Harris and didn’t know much about her,” said one campaign official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “So it was incumbent upon her to fill the void. Instead, they let Republicans define her.”

As dispiriting as those individual conclusions are, the big-picture view among some Democrats was even more fatalistic. The party, they fear, has let their opponents claim for themselves the most significant development in information technology since Gutenberg invented the printing press.

“Overall,” said a party strategist, “we have just lost the internet.”

It wasn’t always this way. Sixteen years ago, Democrats, led by Barack Obama, appeared to have the advantage in the political communication wars. The party had moved quickly to capitalize on the internet as a news and organizing tool, one that would only grow more valuable as younger (more liberal) users moved more of their daily lives online.

Things began to change with Donald Trump. His campaign used Facebook to great effect in 2016, recognizing the potential for reaching its aging membership without putting up the sort of money necessary for ad buys with traditional media. As the media ecosystem became more balkanized and as conservatives began branching out in different directions—experimenting successfully with podcast and YouTube shows, and cheering on their ideological allies as they acquired top social media properties—that advantage became more pronounced.

But instead of aggressively contesting this territory, Democrats conceded it and moved instead to build their own. The results have been mixed. While a number of influential progressive media properties have emerged in the Trump era, they have not succeeded in widening the party’s base or attracting the interest of others outside the tent more generally. Their primary upshot has instead been a form of epistemic closure. Democrats are largely talking to each other in closed rooms while an entirely different and more freewheeling conversation takes place among conservatives and the politically unengaged.

“I think there is a massive part of the country, well beyond Trump loyalists, who are almost completely insulated from bad news about Trump,” said Jesse Lee, a longtime comms operative in Democratic circles, who has worked for, among others, Barack Obama and Nancy Pelosi. “It’s not on their TV because they watch Fox. And their social media filters it all out. The same goes for any positive news about Democrats. It’s absolutely the case that Dems need to look at any opening in those information environments and build whole new infrastructures to penetrate them.”

THE IRONY, IN PART, IS THAT this development accelerated under Joe Biden, who for decades had been known as one of the Democratic party’s most loquacious (if endearingly gaffe-prone) and media-friendly members. Biden was a fixture of the Sunday shows, was chummy with certain newspaper columnists, and was always good for a memorable quote.

But in 2019 and 2020, he was also getting older—not yet as noticeably infirm as he would become in the White House, but a step or three slower. During the primary, his staff took a cautious approach to media engagement, keeping him off many alternative platforms and declining TV invitations.

When the COVID pandemic hit, people read that risk-averse posture differently. But it was still low-engagement. And that didn’t change when Biden entered the White House. Michael LaRosa, Jill Biden’s former press secretary, recalled how the East Wing refused to do the Today Show if Savannah Guthrie was hosting because his staff was still angry about a February 2020 interview during which Guthrie asked Biden about son Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine.

That was a one-off decision made out of pique. There were other media engagement decisions that were rooted in a larger strategy. One of the more interesting and consequential ones had to do with Fox News.

The conservative cable network has long been a bête noire of liberals. During the Trump years, many of them called for boycotting the network. The first target was companies that advertised on Fox News. The next target was Democratic politicians themselves. During the 2020 primary, they were pushed to avoid Fox. Eventually, the Democratic National Committee decided to exclude the network from hosting debates after an article in the New Yorker revealed network executives had an unusually close relationship with the Trump administration.

In the aftermath of the 2020 election, the extent to which Fox News had not been an apolitical actor became clear. The network would eventually settle a $787 million defamation lawsuit with Dominion Voting Systems over lies it repeatedly aired about the voting machine company. But White House aides still had to contend with the network’s massive audience (more Democrats watch Fox than any other cable network) and its capacity to make life difficult through its coverage and programming. They chose to keep Biden away. While he often engaged in back-and-forths with the network’s White House reporter, Peter Doocy, the president never sat down for an interview.

“In what world does it make sense for a candidate or president to alienate millions of voters for five straight years, many of whom are Democrats, by just ignoring a massive cable platform with the largest audience on cable and sometimes on television?” said LaRosa. “Negative narratives about Joe Biden were often being birthed and pushed by GOP guests and politicians on that network. Why would you forfeit a massive platform to make your case, defend yourself, or promote your agenda and sell your accomplishments for the duration of your candidacy and presidency?”

LaRosa said that after he pitched his colleagues on Jill Biden appearing on the network, he was “told emphatically that she was not allowed to go on Fox News ever again.”

HARRIS HAD HER OWN rocky relationship with the press, stumbling out of the gate as vice president when tasked with trying to stem migration from the Northern Triangle countries. But she was clearly more capable than Biden, something that had become especially clear by the time he decided to drop out of the race.

Still, the campaign team was made up, at least initially, of Biden veterans, and they retained a certain cautious outlook on media engagement. And officials close to Harris say that her own aides were concerned that she would suffer a damaging moment—as when she appeared caught off guard by questions about why she hadn’t visited the border during an infamous Lester Holt interview early in her tenure as VP—or appear scripted and inauthentic.

There was also another concern: time.

Harris had to quickly make scores of calls and host dozens of meetings with key stakeholders throughout the Democratic party in order to whip their support. She had to embark on a vice presidential nominee-vetting process. She had to staff up a repurposed campaign that was originally built around her boss. She had to prepare a stump speech and a policy platform.

Amid all this activity, one thing she needed to temporarily sideline was media engagement. She announced her candidacy on July 21. Her first sitdown interview was on August 29.

Harris eventually reprioritized. She ramped up her media appearances, went on nontraditional platforms, joined podcasts, and in mid-October, she even sat down with Fox News. But privately, Democrats fretted that her media blitz campaign came too late and that it was also fundamentally misconceived: Aside from her tussle with Bret Baier on Fox, she’d done little to win over Trump-curious voters or introduce herself to non-engaged audiences.

The campaign tried to fill in the blanks as they went along. Their approach involved giving major access to social media influencers, who were invited to produce content from her events. There also was an incredible premium placed on YouTube, which the campaign and its allies saw as their hidden weapon to reach online audiences—particularly black voters. Future Forward, the Harris-backing Super PAC, spent $51 million on YouTube ads, according to an official there.

But, unlike Trump, who spent hours on podcast interviews and YouTube shows multiple times a week, Harris appeared in precious little of that campaign content herself.

Her campaign was in talks to have her on Joe Rogan’s podcast, the most popular in the country. The campaign official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said conversations with Rogan’s people continued until late October, with the podcast host’s team relaying that it would be more conversational than adversarial. But the logistics never worked out.

Ultimately, there was no appetite to attempt to make inroads into other, similar forums. Beyond Harris’s Fox News appearance, the campaign official said, “there was no thought to go outside of the like-minded ideological bubble.” A person familiar with the conversations said Fox News approached Harris’s team for additional sitdowns, including multiple offers to appear on the morning show Fox & Friends, one of which would have been a telephone interview the Saturday before the election. The campaign team declined.

Instead, they leaned on four surrogates—Mark Cuban, Sens. John Fetterman and Bernie Sanders, and Pete Buttigieg—to do the heavy lifting when it came to engaging the male-dominated podcast culture and online media that Trump’s team had spent months cultivating. Some Democrats were left deflated.

“A lot of these podcasts that Trump did, yeah, they’re somewhat right coded,” said the campaign official. “But Theo Von, Rogan, even Barstool, the audience there is pretty nonpartisan, and if you look at it, it’s a mix of Democrats and Republicans and independents and a lot of people who just don’t give a shit about politics. It was a really big missed opportunity.”

WITHIN DEMOCRATIC CIRCLES, the debate over how much party officials should engage adversarial media—Fox chief among them—has centered on two questions: First, will you get a fair shake? And second: Will you end up legitimizing an outlet that you’d rather marginalize?

For years, liberal media watchdogs—Media Matters for America, most prominently—have argued that there are clear answers to both of these questions: No, you won’t be treated fairly, and yes, you will legitimize them, whether you want to or not. For those reasons, they have argued against engagement.

Not everyone feels this way. Some party operatives stress that the debate over legitimizing Fox News specifically is, to a large degree, immaterial—that the network’s legitimacy should simply be accepted as a fait accompli. After all, a vast swath of the country regards Fox as legitimate. Boycotting it is more likely to delegitimize you among its viewers.

“The goal of being in politics, if you sign up to be in this arena, is to do persuasion, is to get people who disagree with you to agree with you. Politics is the discourse of trying to get people to move to your side,” said Faiz Shakir, Bernie Sanders’s former chief of staff. He cautioned that there are some hosts on Fox News and elsewhere that he would avoid engaging because of his certainty that they would be not just hostile but unfair to nonconservative guests. But, he added, “if we’re trying to defeat Donald Trump, at the end of the day, you have to engage with people who like him.”

Among the prominent Democrats who have adopted this ethos is Buttigieg, who made his appearances on Fox News a selling point of his run for the Democratic party’s presidential nomination in 2019. He was a deft communicator eager to step into the clamoring arena.

The end of the 2024 campaign found him once again in this role. Days before the election, Buttigieg appeared on the site Jubilee, which hosts 25-on-1 debates for the purpose of political spectacle. His clip received more than 2.7 million views in three days—not a big number compared with the 47 million views Rogan’s Trump interview has gotten over the past two weeks, but certainly not nothing.

But possibly the most illuminating moment happened outside of public view. As social networks were being inundated with misinformation about the federal government’s response to hurricane relief efforts in North Carolina, Buttigieg decided to call up Elon Musk, a major vector of that misinformation on his own platform, X.

The call was a success. Musk backed off the FEMA conspiracism and even praised Buttigieg for being on top of the situation. But the capricious tech giant did not stop hammering Harris on his platform, posting a mix of increasingly wild conspiracy theories, vicious personal attacks, and doom-filled prophecies about what she’d do as president. Cuban proposed a private conciliatory meeting between Musk and Harris. But Harris’s team worried that Musk would simply leak the conversation, and they declined.

“The things he says about Kamala are so far off, I thought it would be beneficial for them to talk,” Cuban said of Musk. Asked by The Bulwark about the failed effort to connect the two sides, Cuban replied: “I’m not talking politics at all till after January 20.”

FOR THOSE DEMOCRATS WHO BELIEVE that engagement with adversarial and alternative media is beneficial and caution is imprudent, the 2024 campaign can be taken—arguably—as a case in point.

Some Democrats have started to believe voters were not turned off by Trump’s myriad controversies and conspiracies precisely because his media ubiquity helped create a different, more multifaceted, sanded-down persona. While liberals hyperventilated over John Kelly’s warning about Trump’s fascist tendencies, normies were listening to the man talk about UFC fighting with Rogan, or watching clips of him making fries at McDonald’s.

There is reason to believe that this approach can be adopted by Democrats, too. Jeff Jackson, the North Carolina Democrat who has created a huge following with his straight-to-camera TikTok posts, won his race to become attorney general of his state, even as Trump triumphed there.

The media-positive approach won’t work for everyone. Adversarial interviews can be crisscrossed with tripwires, while podcast conversations can become tortuous philosophical conversations lasting hours and yielding clips of candidates at their lowest energy.

“You don’t want to go on there and find it did more damage to you because you weren’t able to accomplish the persuasion you wanted,” said Shakir.

But increasingly, all factions within the Democratic-progressive movement are warming to the idea that the party has to move more outside of its media cocoon if it wants to chart a path back to power.

Angelo Carusone, the president of Media Matters for America, said he remains skeptical that Fox News appearances would help Democrats, warning that the network would bury whatever positives came from a sitdown under a heap of negative followup coverage. He said that progressives need to build up their own outlets and networks first, the better to amplify good coverage.

But as a practical matter, Carusone said, Democrats would be wise to engage with non-overtly political podcasts like those hosted by Theo Von, Tony Hinchcliffe, and Shane Gillis. He even recognized that the better communicators should appear on Fox News, provided they have a plan for the ambushes that will come.

“I generally believe this idea that we have to go to that terrain because they control the terms of the discussion is a huge mistake,” he said. “They’re not going to let you go on and have a clean hit. But I’m not opposed. There just has to be a muscular approach.”