Biden’s Fragile Plans

Democrats have big spending plans but may lack the votes. Is it too late to turn toward bipartisan deal-making?

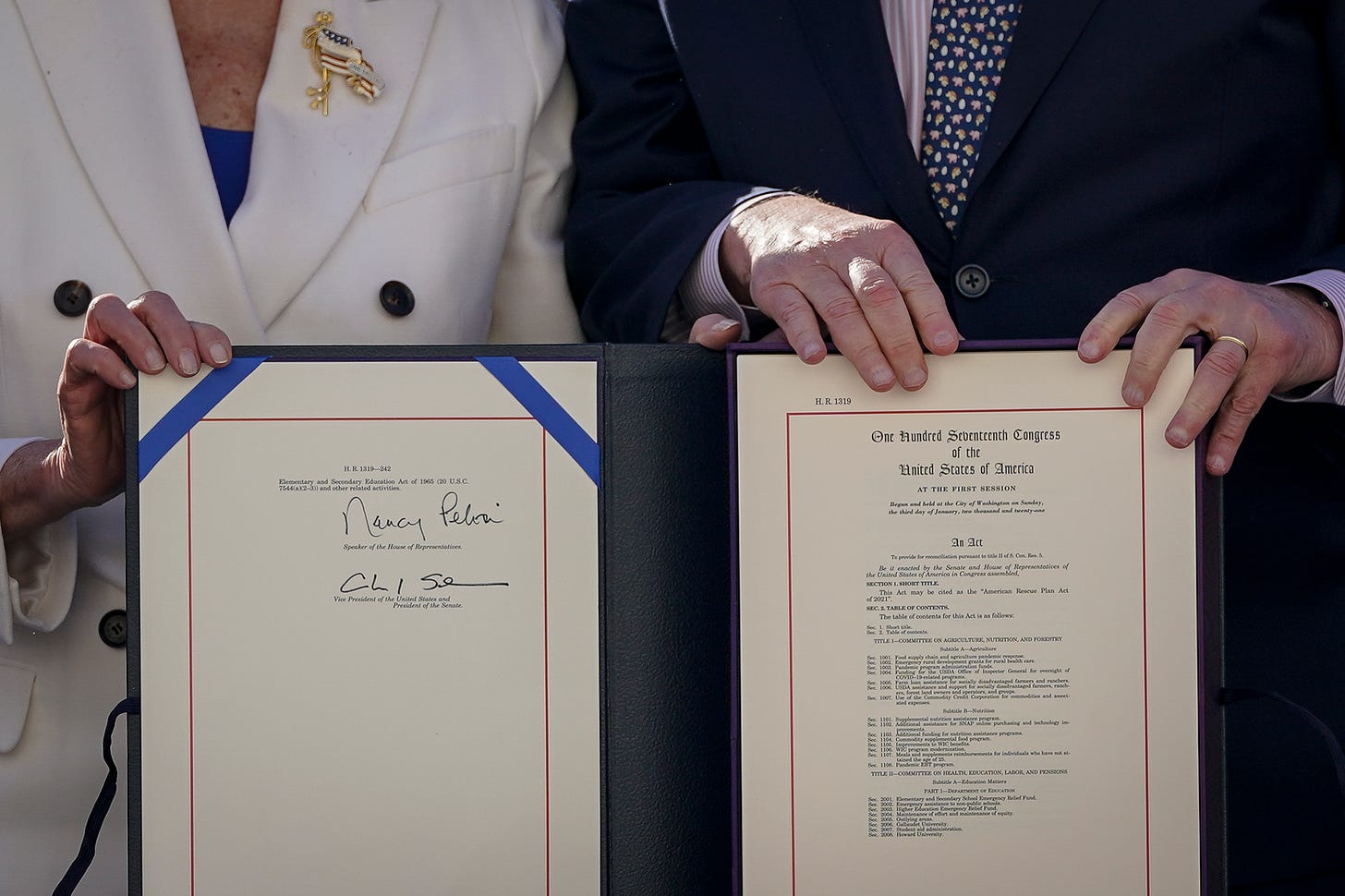

Democrats are exultant over the passage of President Biden’s $1.9 trillion COVID-response bill. It passed Congress with no Republican support, and thus was written without the compromises that can dampen partisan enthusiasm. If the economy booms in the second half of the year, as is expected, Democrats can run against the GOP for opposing the law that—they will claim—made the good times roll again.

This exhilarating experience has Democrats wanting more—much more. The administration is said to be prepping a $3 trillion spending initiative for infrastructure, green energy, “human capital” investments, and much else. Politically, the president’s top aides are signaling that they will try to coax GOP support for their plans but expect to fail. And when they do, they will proceed as they did with the COVID bill, by using budget reconciliation to pass whatever can muster Democratic-only majorities in both chambers.

Even granting that it is impossible to work with most congressional Republicans these days (as they are uninterested in governing), the emerging Democratic strategy is both risky and dispiriting.

The election of Joe Biden as president last year was said to be an opportunity for center-out deal-making that would counter the polarizing forces crippling American democracy. But that is not what is happening. Democratic victories in both Georgia Senate races in early January created a new calculus. With their party somewhat unexpectedly in the majority in both congressional chambers, Democrats decided that this is the year for another historic expansion of the government’s role in American life.

There’s just one problem: Democrats were not swept into power in 2020 like they were in 1932 or 1964. In 1965, Democrats held an astonishing 295 House seats, and 68 in the Senate. Currently, there are just 219 Democrats in the House, and 50 in the Senate. There are few votes to spare on any question.

That was not a barrier to enacting the COVID bill, but spending money during an emergency—with a focus on sending checks to millions of households, and without the need for offsetting tax hikes or spending cuts—is not a particularly heavy lift.

The same cannot be said of what is reportedly being planned for the rest of the year.

Some congressional Democrats might want to repeat the COVID playbook for their upcoming agenda, by eschewing offsets and adding more to the ballooning federal debt. But that door has (thankfully) closed. After enacting $6 trillion in emergency relief over the past year, key Senate Democrats—such as Angus King—are balking at continuing down this path. All new spending will need to be paid for with tax hikes or spending cuts, or it will not pass.

That requirement alone pushes these bills onto more treacherous political terrain. The Biden administration is eyeing an increase in the corporate tax rate, which would partially reverse the cut included in the Trump tax plan of 2017. Not surprisingly, many Republicans are unenthusiastic about this possibility, but so too is big business. It is one thing to push aside the GOP minority; it is another thing altogether to overcome the unified opposition of the country’s largest enterprises, with no votes to spare in the Senate.

That is but one example of the many controversies that will need to be navigated to secure passage of an expansive (and expensive) agenda on an entirely partisan basis.

There is another possible path forward, however unpalatable it may be to many Democrats. While most Republicans are uninterested in finding common ground with the new president, there is a substantial subgroup—ten at least—in the Senate who are open to genuine compromise. With their support, strong legislation could pass easily in the upper chamber. Without it, every bill will be a cliffhanger, and some will not make it.

The president—or, more likely, his aides—rebuffed a deal with this group on the COVID bill on the grounds that the requested concessions were too costly. Democrats saw an opportunity for a $1.9 trillion bill written entirely on their terms, and getting the support of ten Senate Republicans was not worth jettisoning $1 trillion of their planned spending.

That decision may have appeared to have time-limited implications. Once the bill was done, new deals still could be struck with willing GOP senators on legislation assembled later in the year.

That may still happen, but recent political events can influence next steps. The Republican senators willing to cut a deal on the COVID response plan may feel burned by the experience. Moreover, many Democrats are likely to think they would rather not secure bipartisan support for their agenda because it would only water down their initiatives. In other words, the cycle of polarization has been reinforced, and is therefore more likely to continue.

The 2022 midterm election is also on the horizon. The president’s party typically loses seats in these contests, which may incentivize his party to secure what they can before they lose power. That too fits the pattern of recent years, with both parties playing for unilateral victories when they are in power rather than striking lasting compromises that might foreclose their options.

The Biden presidency started with much hope that the worst aspects of the toxic politics of recent years might recede, even if only a little. The rhetorical tone has certainly improved (it could hardly have gotten worse). But the incentives for partisan legislating are as strong as ever, and are crowding out the possibility of a comeback for consensus deal-making.