Biden’s Trip to Jeddah Is an Admission That His Saudi Policy Has Failed

His instincts to promote democracy and human rights were good, but he moved too quickly and too clumsily.

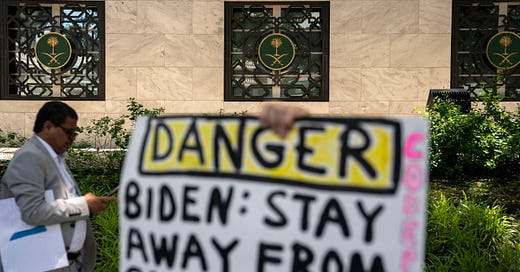

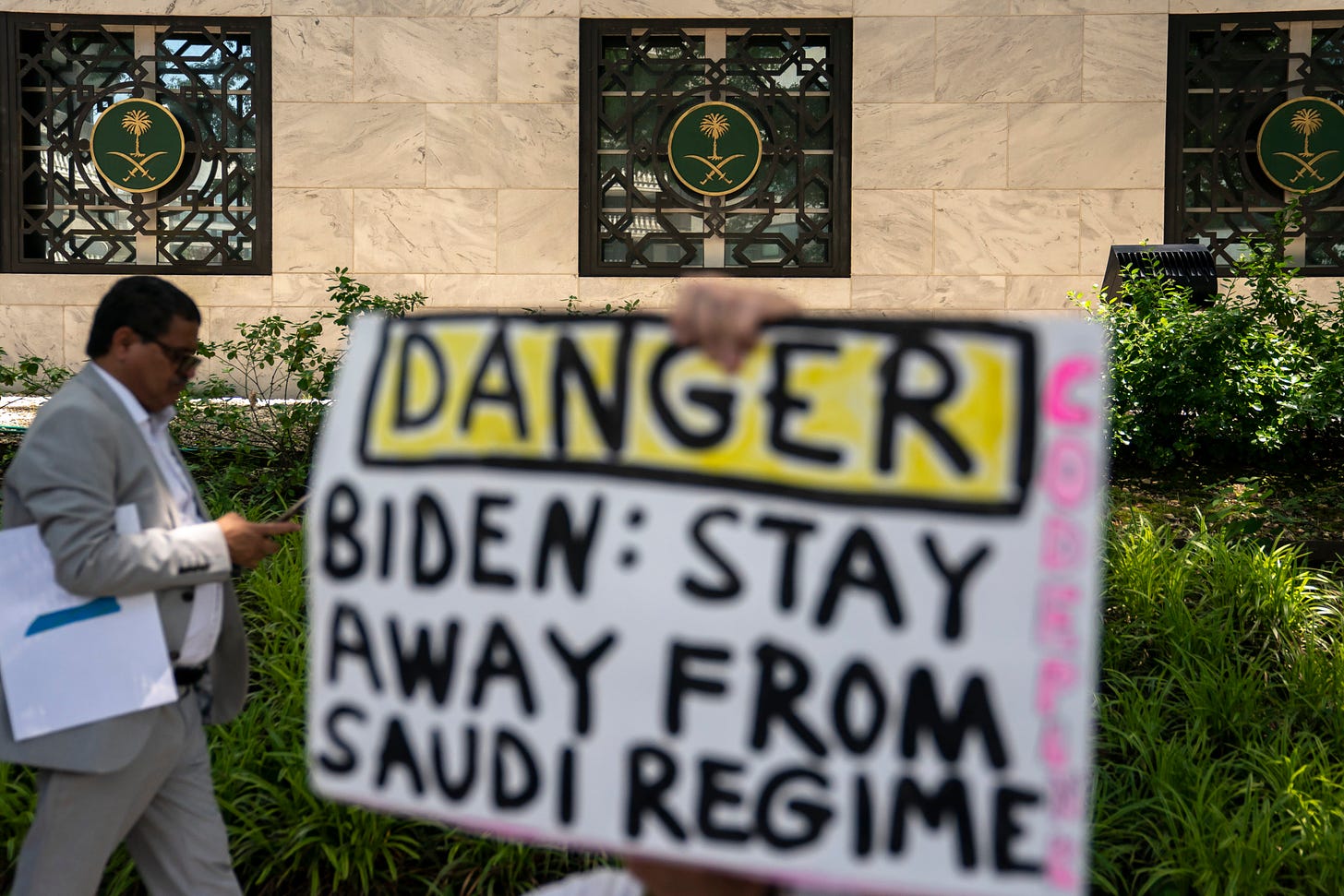

President Joe Biden is officially going to Saudi Arabia, one of the few American partners with whom he wanted more distance, to ask for help. As a candidate, Biden declared Saudi Arabia a “pariah state,” and upon taking office, one of his first major foreign policy decisions was to change the U.S. government’s tone and policy toward Saudi Arabia, which for decades had gotten away with murder—literally—because of its influence on global oil market. But the administration decided to make up for all the mistakes of the past decades at once. The campaign won the president some positive coverage, but it created a standoff between the two sides, and now the president has to embarrass himself by asking Riyadh to pump more oil and bring down global gas prices.

Overall, Biden was right to want some daylight between the United States and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. He has described the world as caught in a struggle between democracy and autocracy, and Saudi Arabia is an autocratic regime. He has identified corruption as a major national security threat, and the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (MBS), shook down most of the country’s elite in a five-star hotel to consolidate his power while making a $2 billion dollar corrupt deal with Jared Kushner. The Saudi campaign in Yemen has been no more humane than Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine. It includes the targeted attacks against hospitals using American weapons. Within Saudi Arabia, as civil liberties are marginally expanding under MBS, political rights are contracting. The crown prince likes to brag about ending the compulsory hijab law, allowing women to drive, and ending the reign of the religious police on the streets, but he is simultaneously torturing the very women who championed those rights.

Most infamously, at least in the United States, MBS is responsible for the brutal murder of Washington Post columnist and American green-card holder Jamal Khashoggi. Without Khashoggi’s murder, relations would have been much better. Kushner and Donald Trump’s eagerness to overlook the grotesque slaughter of Khashoggi created immense public demand for Biden to be tough on the Saudis—the kind of public demand that makes it hard to manage a complicated relationship at the best of times.

President Biden should blame his predecessor and his Saudi counterpart for the state of relations, but he should blame himself and his national security team more. To make up for Trump’s anything-goes-as-long-as-you-grease-my-palms foreign policy, the Biden administration decided to embarrass MBS by publishing an intelligence report concluding that MBS was directly responsible for Khashoggi’s murder, and then adopting retaliatory policies, which will come to shortly, that the entire Saudi regime would have to pay a price for it. It’s not clear exactly what the strategy of humiliation was designed to accomplish, but it’s conceivable that if Biden had limited his critiques to MBS personally, other parts of the Saudi regime might have concluded that the crown prince’s barbarity was the irritant in the U.S.-Saudi relationship.

In its official pronouncements, the administration downgraded Saudi Arabia from an “ally” to a “partner,” implying that the problem was more systemic than merely MBS or his behavior. Two weeks into the administration, the president announced an end to American support for the war in Yemen, hence making Iranian victory easier. It would have been much more prudent to tell the Saudis privately that U.S. involvement would end if Riyadh didn’t change the way it was conducting the war. Even in the likely event that the Saudis didn't find a more humane way to fight and the administration still had to pull the plug, the aftertaste would not have been as bitter. And in February 2021, the administration delisted the Yemeni Houthis, a proxy for Iran, against Saudi (and Emirati) objections—and reality—as a terrorist organization. Punishing the entire regime for MBS had the opposite effect. MBS was previously walking on thin ice, but the Saudi establishment reacted by rallying behind him in self-defense.

It would be regrettable if the administration were mismanaging a delicate relationship with an unsavory partner for good reasons. But it’s pathetic to sacrifice relationships with the Saudis in the vain hope of resuscitating the nuclear arms agreement with Iran.

It’s even worse that the administration’s policy toward Saudi Arabia seems to have spilled over into its policy toward the United Arab Emirates, with equally confusing and self-defeating results. Delisting the Houthis was an olive branch to the Islamic Republic which only increased their appetite for terrorism. Earlier this year, they attacked the UAE, killing a civilian. The administration still declined to relist the Houthis as a foreign terrorist organization. Worse, it took over a month to send a delegate to hear the concerns of the Emiratis. And even then, it was a general who was dispatched, not a member of the cabinet or a Biden confidante. It was another signal that the administration doesn’t care about its relationships with the Arabs.

The Saudis and the Emiratis deserve condemnation for the humanitarian catastrophe in Yemen, but this doesn’t mean Iran and the Houthis—who are at least as responsible for the atrocities there, if not more—deserved rewards.

There have been more futile sacrifices at the altar of arms control agreement with Iran. The administration has not kept regular communications with the Saudis and the Emiratis about the developments of the talks with Iran, though Riyadh and Abu Dhabi stand to lose a lot if Iran receives billions of dollars in unfrozen assets and has sanctions against its economy lifted. The Emiratis finally signed onto the United States’s decades-long Arab-Israeli peace project, and the Saudis are getting closer. Both have shown no intent to violate America’s longstanding policy of nuclear non-proliferation. Iran, on the other hand, is getting more aggressive against America’s closest regional partner and is developing nuclear weapons. In other words, for the past year and a half, the U.S. government has been playing nice to Iran and kicking the Arabs, as though it were the Saudis and Emiratis with the blood of hundreds if not thousands of Americans on their hands and the Iranians who had been reliable security partners, rather than the other way around.

This arrogance mirrors how the Obama administration treated the Arabs and the Iranians, when many of the members on Biden’s national security team were in slightly more junior positions. In Saudi Arabia and the UAE, they are remembered as those who stomached a genocide in Syria, oversaw the handing over of Lebanon to Hezbollah, and were so impatient to be done with the Middle East that they left their partners to face the twin terrors of the Islamic State and Iran.

Off the record, Obama-Biden officials talk about empowering Iran to create a balance of power in the Middle East and keep the peace so America can get out. But this is not how one treats reliable partners, not to mention that the terms “Islamic Republic of Iran,” a theocratic mini-empire, and “balance” have no business being in the same sentence. As long as America is talking about leaving the region and mistreating its partners, though, the Arabs will need a big brother to protect them, and they are betting on China and Russia, both of which have significant influence over Iran.

The unfortunate truth is that the administration’s instincts were at least partially reliable, and it could have done much good if it didn’t come in too hot, expecting perfection and peace overnight in a region where, more than anywhere else, progress must be graded on a curve. The trouble began when Biden began to treat Saudi Arabia, not Iran, as the pariah he had declared it to be, and threw in the United Arab Emirates for good measure. Now that Biden needs something from the Persian Gulf Arabs—the same thing every American president has needed for nearly a century, only more—he must forgo even modest improvements in Saudi behavior and embarrass himself.

The United States has rarely—perhaps never—been able to push for change in countries it has bad relations with and no leverage over. The Carter and the Reagan administrations succeeded in forcing change—for the worse in Iran and Nicaragua; for the better in Chile, South Korea, Indonesia, and the Philippines—precisely because the diplomatic ties were strong and they had plenty of leverage.

Because of the Biden team’s awful Middle East policy, now the Arabs have the upper hand, and relations are awful. Biden was right to want Saudi Arabia to be better, and he could have accomplished that if he had treated them better. But now, change will have to wait.