Blaming Democrats for McCarthy’s Fall Is Bullshit

It’s a tendentious, historically ignorant argument. Why insulate Republicans from the consequences of their actions?

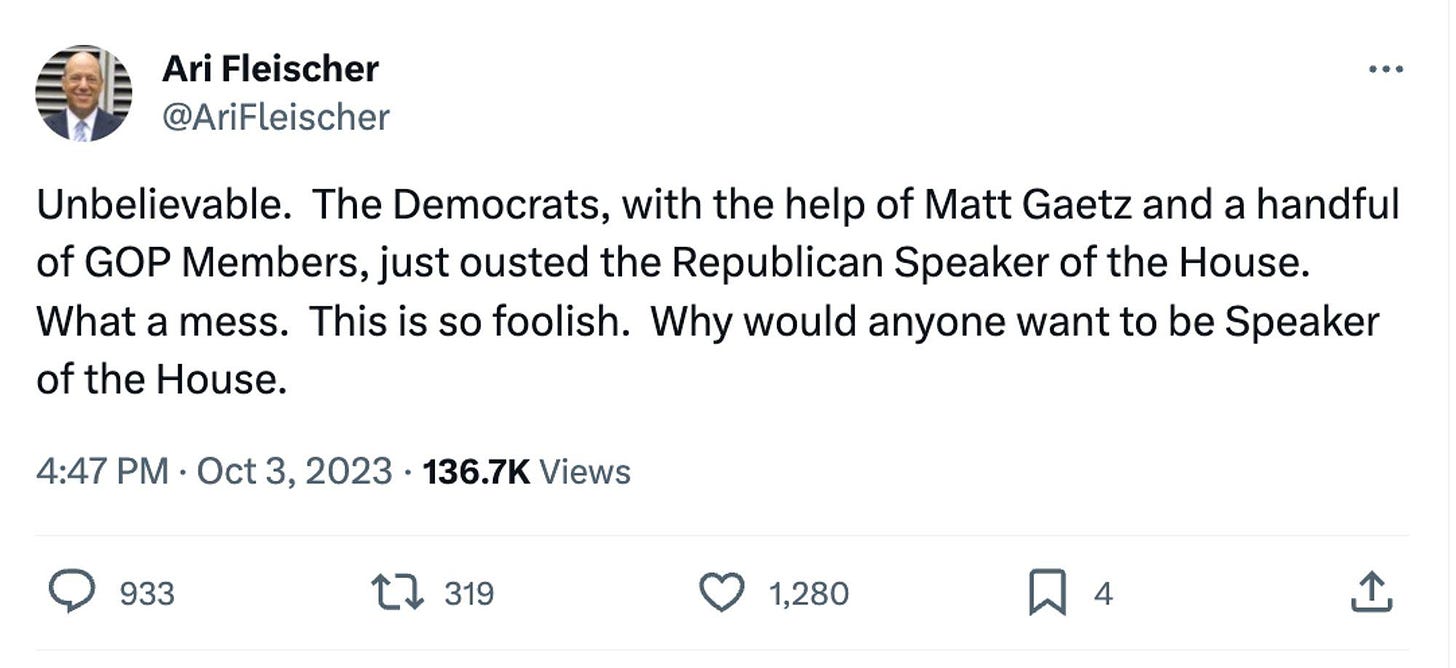

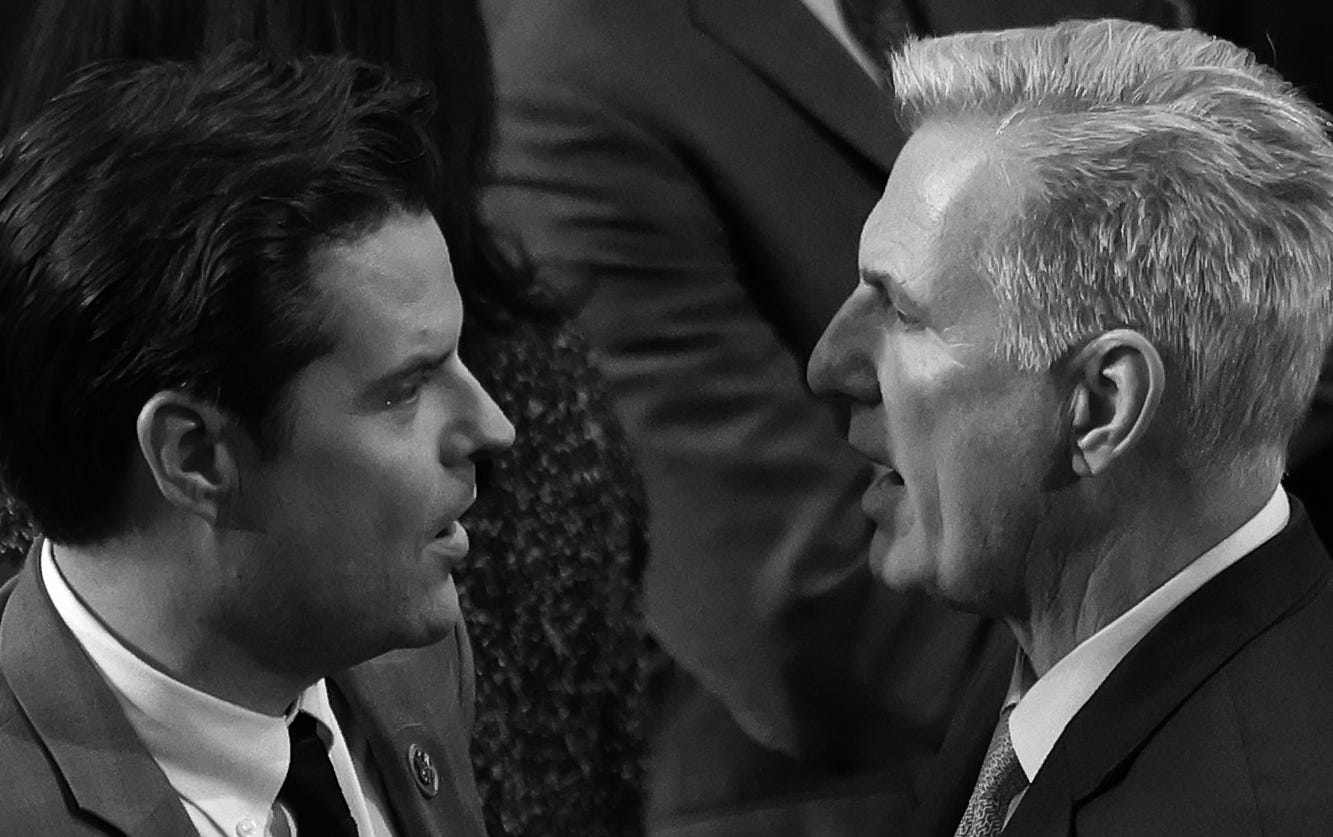

LET’S GET THIS STRAIGHT: Rep. Matt Gaetz, a Republican, called a vote to oust Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, a Republican, in accordance with rules crafted at the start of this congressional session by the chamber’s majority party, the Republicans. Yet ever since McCarthy’s ouster, Republicans and conservative commentators have been angrily blaming . . . Democrats.

They’re lashing out with petty “revenge,” such as forcing Nancy Pelosi and Steny Hoyer to give up their “hideaway” offices in the Capitol. All because Democrats did what every House caucus always does—support someone from their party for speaker over someone from the other party.

Indeed, going back at least seven decades, only once has a representative voted for the speaker nominee of the other party—back in 2001, when perennial oddball Jim Traficant, a Democrat, voted for Republican Dennis Hastert. In response, Traficant’s Democratic colleagues denied him any committee assignments; he would be expelled from Congress a year later after getting convicted of various felonies in federal court.

Yet Republicans and conservative writers have spent days griping that Democrats didn’t do what no one ever does. Here are just some of the complaints:

Republicans’ blame-the-Democrats argument is bullshit. It resembles a drug addict reacting angrily to an intervention, or blaming it all on their parents who, after years of financial support and cleaning up messes, finally cut them off. It presumes that insulating the GOP from the effects of MAGA craziness helps America. In fact, the opposite is true.

TO UNDERSTAND WHY the blame-Democrats argument is bullshit, let’s walk through the situation, starting with an obvious detail: All other things equal, having someone as speaker of the House is better than leaving the office vacant. And yes, it’s possible that whoever eventually gets the job will be a downgrade. McCarthy made a deal in May with President Joe Biden to avert default and this month he helped avoid a government shutdown. These measures passed with bipartisan majorities—rather than deliberately tanking the American economy on behalf of a congressional minority because law enforcement won’t give Donald Trump permission to commit crimes without consequence. That’s what counts as being an “adult in the room” in the modern GOP.

But McCarthy was part of the problem. His work advanced the lie-embracing, anti-democracy efforts of Trump and the MAGA movement.

As House minority leader in January 2021, McCarthy voted to reject the Electoral College votes from Arizona and Pennsylvania, two states that Trump lost, and lied to the American people by claiming that the election had been stolen from Trump. McCarthy justified this by repeating post-election lies Republicans were telling.

Three weeks after January 6th, with Americans—including a large majority of Republican voters—appalled by the violence that broke America’s long streak of peaceful transfers of power, McCarthy traveled to Mar-a-Lago for a meeting and photo with the instigator of that violence. Rather than trying to move his party beyond the insurrectionist former president, McCarthy was instrumental in tying the post-January 6th Republican party back to Trump.

McCarthy also tried to prevent a congressional investigation of the January 6th attack. After he failed, he got Republican Rep. Liz Cheney kicked out of GOP leadership and then exiled from the party for telling the truth about Trump’s coup attempt and the violence it caused, rather than downplaying or defending it.

Recently, McCarthy opened an “impeachment inquiry” into President Biden based on more things Republicans are making up. Expert witnesses Republicans brought in for the first hearing testified that they haven’t seen evidence of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Even proponents of the proceedings can’t articulate what actual abuse of power they’re accusing Biden of, relying instead on insinuations built on accusations of things his son Hunter did years before Joe Biden became president.

The transparent goal is to try to counterbalance Trump’s two impeachments—both of which were for clear abuses of power.

As the Washington Post’s Greg Sargent notes, “Republicans essentially want Democrats to stand by while they indulge MAGA in all kinds of sordid ways and then rush in to provide votes when MAGA’s demands grow so problematic for Republicans that the GOP conference can’t hold together.” In other words, the supposed reason to help Republicans keep hurting the country is because otherwise they’ll hurt the country.

It’s the political version of “Mom, Dad, bail out my coke dealer, because if you don’t I’ll eventually find another one and they could be worse.” The right response is “No.”

EVEN IF DEMOCRATS SHOULDN’T HAVE SAVED MCCARTHY because he was actively attacking the constitutional order, there’s another argument that they should have saved him to gain leverage, and use it to counteract the pull of the MAGA right.

Here again, the addict analogy offers a simple refutation. Much like an addict’s binges say more than their insistence they have things under control, McCarthy’s actions show openness to leverage only from the most extreme parts of the Republican caucus.

The only reason Matt Gaetz could call a vote to vacate is that McCarthy gave Gaetz, and every other Republican, that option as a condition for making McCarthy speaker. In January, when Gaetz and 19 other Republicans originally denied McCarthy (or anyone) the necessary majority to win the speakership through multiple rounds of voting, McCarthy could have tried to cut a deal with centrist Democrats to sideline the radical Republicans. He chose the opposite, promising to do what the extremists wanted, and granting them power to threaten his job if he didn’t.

When Gaetz exercised that power, McCarthy again could have tried to form a moderate coalition and sideline the radicals. Again he showed his priorities, saying he wouldn’t give Democrats anything to get their support.

But maybe they should’ve saved him anyway, to ensure that issues they care about come to the floor. For example, Megan McArdle argues in the Washington Post that, “Every likely candidate for speaker is at least as conservative as McCarthy, and at least one plausible candidate, Jim Jordan (Ohio), is much more so.”

But while it’s true that a more MAGAesque successor speaker might block bills that have majority support and that address important issues if a MAGA minority disagrees, McCarthy already showed himself to be contentedly beholden to MAGA.

Another example of this error came from Jake Sherman of Punchbowl News, who warned that “additional funding for Ukraine is going to be extremely difficult” under whoever replaces McCarthy as speaker. But McCarthy wouldn’t let Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky address Congress when visiting the United States last month, and refused a forum where representatives could hear from Zelensky and ask questions (the Senate held one). The House Republicans brought the government to the brink of shutting down, and McCarthy kept it open at the last second not by securing big spending cuts or additional border security funding as his party supposedly wanted. Not by defunding the Department of Justice or another gambit to protect Donald Trump from the law as demanded by the party’s most radical members. But by removing funding for Ukraine. They kept all other spending levels the same.

Why should anyone be confident that saving McCarthy would have saved U.S. aid to Ukraine when McCarthy had just prioritized blocking it?

Mitt Romney, who since becoming a senator in 2019 has been one of the few Republicans in Congress to stand up to the craziness, put it this way: “Speaker McCarthy made a decision to get as close as he possibly could to the radical wing of his party and by doing that he made it virtually impossible for the Democrats to come to his aid.”

Yes. Obviously.

POLITICAL SCIENTISTS STEVEN LEVITSKY AND DANIEL ZIBLATT, authors of How Democracies Die, argue that radical-adjacent elites play a key role in democratic breakdowns. As the authoritarian threat grows, they’re forced to choose “between joining forces with partisan rivals to defend democracy or preserving their relationship with antidemocratic allies,” and when they opt for the latter, democracy is in trouble.

The starkest example is 1930s Germany, when conservatives partnered with the Nazis to oppose the left, believing they could control Hitler. But it applies to a variety of cases, including Hugo Chávez in 2000s Venezuela.

As Trump and the MAGA movement attack American institutions, Republican elites enabling them is a much more serious danger than the marginal difference between Kevin McCarthy and the next speaker. Whoever ends up leading House Republicans, the caucus will be the same.

Insulating Republican elites from the downsides of their actions, such as by helping McCarthy keep his dream job, is like covering for an addict. Letting them enjoy the highs of personal and partisan power while protecting them from political pain just deepens the problem America desperately needs to confront.