Break Up Facebook

For the sake of our civic and political health, the social media giant should be split up.

COVID-19 has friended Facebook.

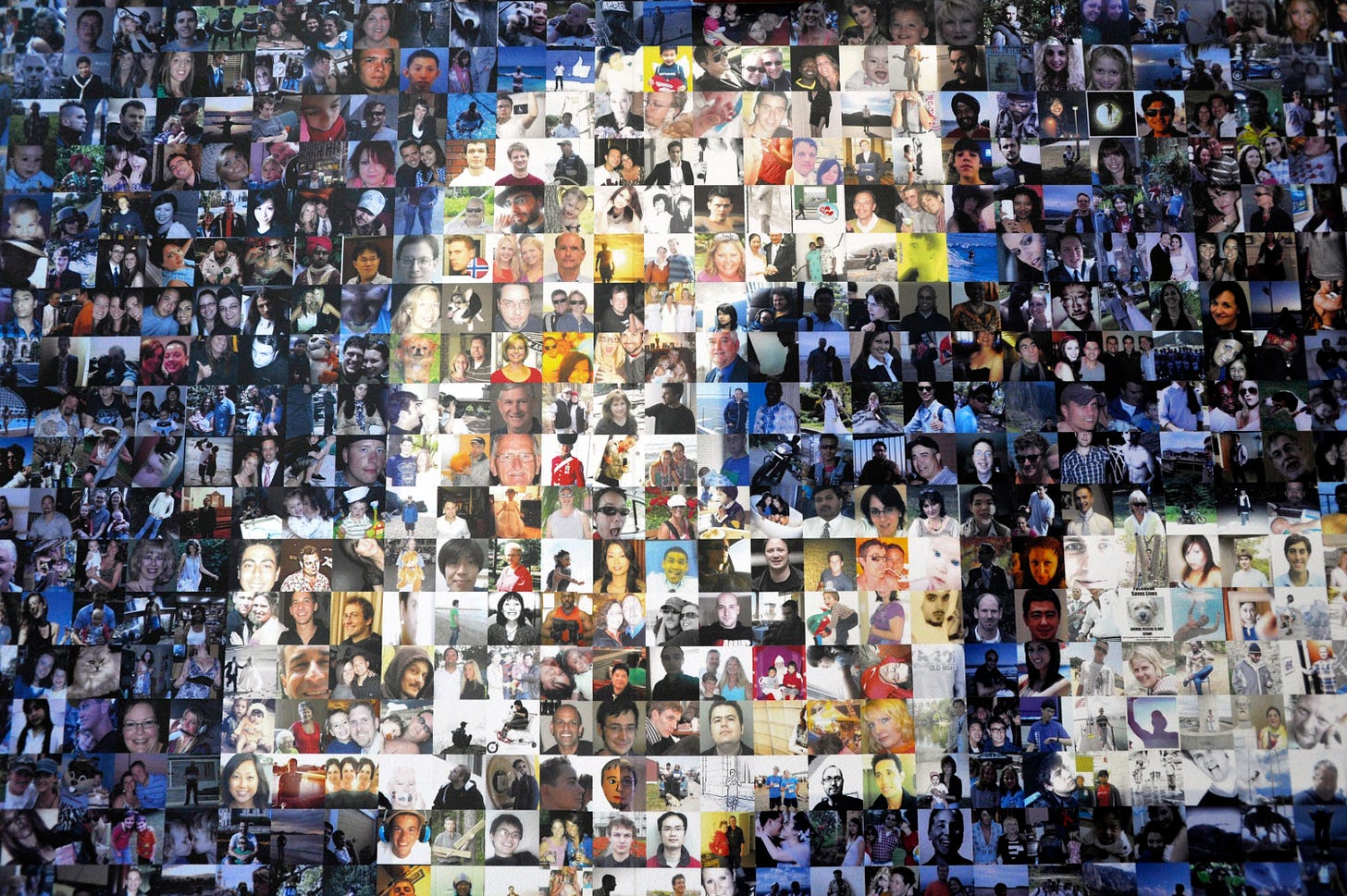

Hungry for information and distraction, nearly 3 billion people a month use Facebook. Audio and video calls on WhatsApp and Messenger have more than doubled in places hardest hit by the pandemic. Facebook has developed a rival to the omnipresent Zoom.

While COVID-19 has temporarily reduced advertising revenue, with $60 billion on hand Facebook can outlast its rivals; as the predominant social media platform, it will corner an even higher percentage of the digital advertising dollar. Inevitably, Facebook will emerge from this pandemic more powerful than before.

But Facebook is not our friend.

Among its principal sources of profit is hosting Donald Trump’s sociopathic advertising campaign for re-election, rooted in the mass proliferation of disinformation, dishonesty, and divisiveness. When traditional news organizations refuted Trump’s dangerous suggestion that Americans inject themselves with household cleaners, his unimpeded quackery went viral on Facebook.

How did Facebook become the ubiquitous shaper of America’s political consciousness—free from the constraints of regulation, competition, and respect for truth? By relentlessly smothering would-be competitors who might have offered something better.

As social networking spread to the great majority of Americans, Facebook bought more than 80 companies that presumed to enter its digital space. Sometimes it absorbed them; frequently it simply shut them down. Not once did the government intervene.

Two acquisitions stand out. By combining a camera app with a social network, Instagram threatened to outstrip Facebook’s popularity. Instead of competing with Instagram, in 2012 Facebook absorbed it. A few years later Time assessed the impact: “Buying Instagram conveyed to investors that the company was serious about dominating the mobile ecosystem while also neutralizing a nascent competitor.”

To protect its flagging Messenger, Facebook blocked other messaging services from appearing or advertising on its platform. But having failed to obliterate its principal rival, WhatsApp, Facebook just bought it in 2014—the climax of its hydra-headed efforts to eliminate competition for Messenger.

Snapchat presented a different competitive threat. As Chris Hughes—a Facebook cofounder who left the company in 2007 and has since grown disenchanted with it—wrote in the New York Times: “Snapchat’s Stories and impermanent messaging options made it an attractive alternative to Facebook and Instagram. And unlike Vine, Snapchat wasn’t interfacing with the Facebook ecosystem; there was no obvious way to handicap the company or shut it out. So Facebook simply copied it.”

Here imitation transcends flattery. As antitrust law expert Tim Wu observes in Wired:

To be sure, there is nothing wrong with firms learning from one another; that’s how innovation spreads. But there is a line where copying and exclusion become anticompetitive, where the goal becomes the maintenance of monopoly as opposed to real improvement. When Facebook spies on competitors or summons a firm to a meeting just to figure out how to copy it more accurately . . . a line is crossed.

Facebook’s program of suppression, acquisition, and imitation closes the marketplace to new ideas and entrants. As Hughes notes, “would-be competitors can’t raise the money to take on Facebook.”

In short, Facebook came to monopolize our attention not by being better, but by being ruthless. This predation feeds itself: Users want the social network most likely to reach others; advertisers crave the largest audience. “Because Facebook so dominates social networking,” writes Hughes, “it faces no market-based accountability. This means that every time Facebook messes up, we repeat an exhausting pattern: first outrage, then disappointment and, finally, resignation.”

Inevitably, Facebook has become the catalyst in degrading a principal safeguard of democracy: American journalism.

In a Pew Research survey conducted in mid-2018 and weighted by demographics, 68 percent of the respondents reported using social media platforms for news, with 20 percent saying they “often” got their news that way. An earlier Pew study, from 2016, found that two-thirds of Facebook users say they get news on the site. But as New York Times technology reporter Farhad Manjoo told NPR, “there’s very little fact-checking that Facebook does,” which has “led to this proliferation of fake news.” Worse, Facebook is “acting as something like the ministry of information for . . . every country in which it operates.” On the latter point, a headline in Business Insider summarized the baneful findings of a three-year study by Oxford University: “Facebook is the most popular social network for governments spreading fake news and propaganda.”

A 2017 report by the Columbia Journalism Review identifies the impact of standard-free social media on mainstream journalism: Diminishing ad revenue. Shrinking readership. An absence of editorial judgment. The loss of transparency and accountability. The elevation of virality—regardless of accuracy—over journalistic quality.

The report elaborates:

Journalism with high civic value—journalism that investigates power, or reaches underserved and local communities—is discriminated against by a system that favors scale and shareability. . . . While news might reach more people than ever before, for the first time, the audience has no way of knowing how or why it reaches them, how data collected about them is used, or how their online behavior is being manipulated. And publishers are . . . at the mercy of the algorithm.

This is toxic to our civic and political health. Warns Chris Hughes:

Facebook engineers write algorithms that select which users’ comments or experiences end up displayed in the News Feeds of friends and family. These rules are proprietary and so complex that many Facebook employees themselves don’t understand them. In 2014, the rules favored curiosity-inducing “clickbait” headlines. In 2016, they enabled the spread of fringe political views and fake news, which made it easier for Russian actors to manipulate the American electorate.

While appropriating one editorial function—deciding what people will read—and discarding another—delivering quality and accuracy—Facebook turned millions of people into lab rats. TechCrunch describes how:

People seized upon Facebook’s single app that pulled together content from everywhere. Facebook began to train us to keep scrolling rather than struggle to bounce around [between news sites]. . . . Emphasizing the “news” in News Feed retrained users to wait for the big world-changing headlines to come to them rather than crisscrossing the home pages of various publishers. Many don’t even click-through, getting the gist of the news just from the headline and preview blurb.

In one decade, Facebook hijacked our curiosity, shortened our attention spans, dulled our critical faculties, and sold our personal data to malign actors.

The paradigm case is Trump’s partnership with Facebook to undermine our 2016 presidential election.

The engine was Facebook’s commoditization of users’ personal data. Roughly 90 percent of Facebook revenues come from advertising, the value of which depends on giving advertisers access to data so granular that they can micro-target what Facebook calls “customized audiences.”

Using Facebook tools, a British political consultancy called Cambridge Analytica—started by the Breitbart-funding right-wing billionaire Robert Mercer—disseminated a “survey” to which roughly 300,000 Facebook users responded. Using the respondents’ data to penetrate the data of their “friends,” the company mined detailed private information on an estimated 87 million Facebook users.

Trump’s digital operation deployed this data in a disinformation campaign that, at its height, spent $1 million a day on ads micro-targeting strategically located Facebook users in electorally decisive states—either by inflaming potential Trump supporters or dissuading possible Clinton voters.

Overall, Trump placed 5.9 million ads on Facebook. In return for this largesse, Facebook assigned an employee to Trump’s digital team to maximize its effectiveness. Together, they succeeded brilliantly.

Moreover, the Brennan Center reports, “Facebook posts by agents of the Kremlin disguised to come across as Americans, promoted by paid advertising and shared by unsuspecting Americans, reached a total of 126 million Facebook users leading up to the 2016 election.” To accomplish that goal, Russian operatives “purchased ads that appeared to promote both sides of divisive social issues in the United States, including police brutality, race, and terrorism.”

After Trump’s efforts became public knowledge, Facebook asserted that Cambridge Analytica had violated its “terms of service” agreements with third parties. Given the tactics employed by Trump and his shadowy Russian supporters, one might think Facebook would instead draw a broader, and deeply sobering, lesson.

Instead, the lesson Facebook drew is this: Licensing Trump’s mass mendacity is a burgeoning source of revenue.

For 2020, Trump’s campaign manager brags, “we have turned the RNC into one of the largest data-gathering operations in United States history”—thanks, he might have added, to Facebook. With Facebook as its engine, the Trump campaign plans to spend $1 billion on what, McKay Coppins reports in the Atlantic, “could be the most extensive disinformation campaign in U.S. history.”

Because Facebook has lowered its advertising rates during the pandemic, Trump will get more deceit for his buck—and Facebook more advertisements. In return, Facebook user data will enable Trump to target individual voters with insidious effectiveness.

Knowing all this, Facebook refuses to ban false deceptive political ads, or to limit Trump’s deployment of user data to reach the right groups with the right lies. Piously, Mark Zuckerberg proclaims that “in a democracy, it’s really important that people can see for themselves what politicians are saying, so they can make their own judgments.”

Based on what? As Zuckerberg well knows, digital media spreads falsehoods with a reach and celerity that defy correction. That’s why Trump partners with Facebook. By January, Trump’s campaign already had spent $27 million on Facebook—including a blatantly false advertisement about Joe Biden’s relationship with Ukraine that Facebook refused to take down.

In contrast, Twitter and Google have barred political advertising. Turning down this advertising windfall was no doubt painful. But as Twitter founder Jack Dorsey explained, “Internet political ads present entirely new challenges to civic discourse: machine learning-based optimization of messaging and micro-targeting, unchecked misleading information, and deep fakes. All at increasing velocity, sophistication, and overwhelming scale. . . . Best to focus our efforts on the root problems, without the additional burden and complexity taking money brings.”

In a tweet that seems directly aimed at Facebook’s hypocrisy, Dorsey adds that it would not be “credible for us to say”—as Facebook has—“We’re working hard to stop people from gaming our systems to spread misleading info, buuut if someone pays us to target and force people to see their political ad . . . well . . . they can say whatever they want!”

It’s worth comparing the Facebook standard to that of another media giant, CNN. A false ad on the cable network is easy for journalists and rival candidates to spot—and, besides, CNN won’t host blatant falsehoods. Not so Facebook. The Brookings Institution reported in December that, “Just last month, CNN rejected two ads from President Trump’s re-election campaign because of inaccuracies. These ads were eventually published on Facebook and other digital platforms as part of a multimillion-dollar ad buy.” Previously, Brookings notes, Senator Mark Warner had vainly urged Zuckerberg to “adhere to the same norms of other traditional media companies.”

By willfully abetting Trump in polluting another presidential election, Facebook may help tilt its outcome. When Slate surveyed experts to name the 30 most dangerous tech companies, Facebook trailed only Amazon: “Its refusal to meaningfully alter the political advertising system that both President Donald Trump and Russian trolls used to their advantage in 2016 suggests that once again one of the main arenas of an ugly election will be Facebook.”

For this continuing civic and political wreckage, only two answers present themselves: empowering government to curb false digital advertising, or using antitrust law to reduce Facebook’s size and sway.

The Honest Ads Act, sponsored by Senators Warner and Klobuchar, would subject digital advertising to the standards for television and radio. By its terms, anyone who pays for political ads the must identify themselves; platforms like Facebook must keep records of who purchases such ads; and foreign nationals are barred from running them.

That would help. But it doesn’t solve the problems of mendacious virality, phony accounts, or automated bots—or the anti-competitive practices that make Facebook so powerful, with such a deleterious impact on journalism.

The most efficacious remedy is to break up Facebook.

The antitrust laws were written to ensure competitive markets, foster innovation, curb price-rigging, and prevent the power of mega-corporations from outstripping governance. Facebook suppresses competition, discourages innovation, and defies regulation—effectively claiming the power to make its own rules.

But beginning in the 1980s, antitrust laws were constricted to a narrow goal—keeping monopolies from gouging consumers. Facebook’s multiple malignancies demonstrate how myopic that is: The company doesn’t charge users; it monetizes their attention, peddling their information. It exemplifies why the law of antitrust exists.

Chris Hughes suggests a start: undo the acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp—creating three separate companies—and bar Facebook from further acquisitions for several years. This should be accompanied by rigorous federal scrutiny of potentially anticompetitive practices.

Granted, this does not directly address Facebook’s role as the platform of choice for degrading democracy. But re-energizing competition in social media may compel Facebook to offer consumers a more honest—and less manipulative—environment for fear of losing market share, while warning Facebook that its diminished role as purveyor of news and political advertising is no longer immune from scrupulous oversight.

From Zuckerberg and Facebook, enough.