Can Democrats Survive the 2022 Midterms?

What this year’s big policy fights—over infrastructure spending and voting rights—mean for next year’s congressional elections.

Already, Democrats can hear the GOP’s footsteps.

For first-term presidents, the modern history of midterms is grim: The president’s party loses an average of about 30 seats in the House and Senate. The most recent Democrats, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, lost twice that. Already Joe Biden has a 50-50 Senate, and a perilously slender House majority of 219-212.

Still, Democrats could hold the Senate in 2022. Of the six contests the Cook Political Report deems competitive, the two tossups involve seats held by retiring Republicans, and a third belongs to the GOP’s poster moron, Ron Johnson.

But the House is poised to flip. Despite Biden’s 7 million-plus popular vote margin, in 2020 the Democrats lost 14 seats. This imbalance reflects an overconcentration of Democratic voters in urban areas, and blatant Republican gerrymandering and voter suppression.

The GOP is doubling down on vote-rigging. The Brennan Center counts 361 Republican voter-suppression measures in 47 states. Moreover, the GOP controls redistricting in states holding 188 House seats—including voter-rich Texas, Georgia, and Florida. A five-seat shift would make Kevin McCarthy speaker.

To buck history, Democrats must change it in two seismic ways, both involving the Senate: breaking the filibuster to enact sweeping electoral reform, and invoking budget reconciliation to pass Biden’s massive infrastructure proposal—thereby transforming America’s governing paradigm.

First, election reform. Together, H.R. 1 and the John Lewis Voting Rights Act combat voter suppression and ban partisan gerrymandering. But to pass them all 50 Senate Democrats must agree on their final versions, and to break or modify the filibuster.

Currently, some moderates balk at the scale of H.R. 1, and Senators Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin oppose abrogating the filibuster. Biden must forge unanimous support for a meaningful version of H.R. 1 and a path through the filibuster for voting-rights legislation. Otherwise, warns Ron Brownstein:

Democrats [should have] no illusions about the fate they can expect. . . . New federal standards for redistricting, election reform, and voting rights... represent [their] best, and perhaps only, chance to preempt the multipronged offensive Republicans are mounting to tilt the balance of national power back in their direction—and potentially keep it there for years.

Still, as Thomas B. Edsall observes: “Even with the passage of the voting rights bill, the [historical] odds . . . favor a Republican takeover of both branches of Congress.” To stave off defeat in 2022, Democrats must turn out their core coalition of minorities and suburban/better-educated whites while adding a critical slice of blue-collar voters.

That won’t be simple. Granted, it helps that today’s GOP reeks of nihilism—disdainful of governance, devoid of ideas, hospitable to extremism, addicted to racism, culturally divisive, contemptuous of democracy, and indentured to a loathsome and dangerous demagogue.

But the Democrats have their own internal tensions. To start, while in 2020 the party gained among white college graduates, its share of minorities declined.

The growing allegiance of upper-class whites owes much to a progressivism, particularly on cultural issues, alien to many nonwhites. Notably, while the Latino vote in 2020 increased by more than 30 percent over 2016, the Democrats’ percentage fell—particularly among men.

By general consensus, causes include the Democrats’ perceived radicalism on issues of culture and law enforcement; a growing assimilation which muted sympathy for undocumented immigrants; a correspondingly diminished self-identification as a disadvantaged minority; and an attraction to the GOP’s perceived aspirational message—self-reliance, entrepreneurship, and upward mobility—which Donald Trump strove to personify.

This last, experts believe, has considerable appeal among men who value their role as providers. Argues GOP strategist Mike Madrid: “Paying rent is more important than fighting social injustice in their minds. . . . The Democratic Party has always been proud to be a working-class party, but they do not have a working-class message.”

Here, Democrats should take the defection of blue-collar whites to Trump as a cautionary tale: absent a strong economic appeal, they have hemorrhaged support on cultural issues. The lesson, Democratic analyst David Shor says, is clear:

If we divide the electorate on self-described ideology, we lose. . . . So the way we get around that is by talking a lot about progressive goals that are not ideologically polarizing, goals that we share with self-described conservatives and moderates. Even among nonwhite voters, those tend to be economic issues.

Here’s a tip for Democrats: The most dramatic example of a Democratic president triumphing in midterm elections is FDR—who, having enacted the New Deal, picked up 9 House seats and 9 Senate seats in 1934.

Joe Biden is aiming for a repeat. Like Roosevelt, he means to transform our economic model, raising the prospects of middle-class and blue-collar Americans across the demographic spectrum. Says Congressman Sean Patrick Maloney of the DCCC: “I do think that President Biden’s policies will be effective at defeating the pandemic and rebuilding the economy long before 2022. The best policy will be the best politics.”

Following enactment of Biden’s stimulus bill, the economy added 916,000 jobs. Economists predict an average of over 500,000 new jobs each month this year, and the Federal Reserve is anticipating growth of 6.5 percent. “I’m not a macroeconomist,” Shor says, “but it seems like Joe Biden might preside over a post-corona economic boom.”

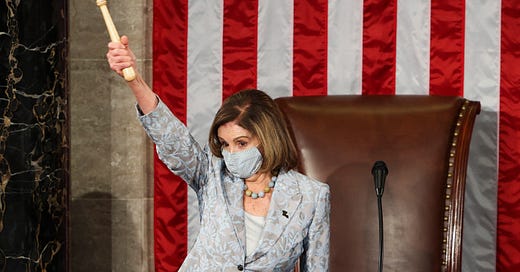

Most Americans will have received some concrete benefit—including a $1,400 check. The stimulus enjoys overwhelming public support—including among blue-collar Republicans—and Biden’s positive approval ratings stand out in ultra-polarized times. Writes Chauncey DeVega in Salon: “I’d much rather be playing Nancy Pelosi’s hand than Mitch McConnell’s hand over the next two years.”

Nonetheless, the Democrats’ chance of retaining their legislative majority after 2022 may turn on the fate of Biden’s $2 trillion dollar “once-in-a generation” proposal to create the “strongest, most resilient, innovative economy in the world” by transforming our decaying infrastructure.

There is near-universal agreement that action is imperative. Accordingly, Biden says, his is “not a plan that tinkers around the edges.” He wants to overhaul our roads, bridges, railways, airports, public transportation, and water systems; provide universal Internet access; support electric vehicles; create green jobs by hastening our transition to clean energy; and attack our housing crisis by retrofitting over 2 million homes and buildings.

Biden’s bid to rebuild our future evokes the great enterprises of our past: not only the New Deal, which brought electricity to America at large, transformed our country’s public spaces, and repaired infrastructure in many cities, but Dwight Eisenhower’s large-scale investment in Interstate highways—both keys to the broad prosperity of the post-WWII era.

But, like FDR, Biden also means to elevate our human infrastructure through another program he will roll out shortly: a massive investment in healthcare, childcare, and education. By fortifying the “care economy,” he would place the economic security of its workforce—often female and/or non-white—alongside that of the blue-collar workers he intends to provide with green jobs and reinvigorated unions.

In short, Biden’s ambitions match those of past epochs. As Jim Tankersley writes:

The scale of the proposal underscores how fully Mr. Biden has embraced the opportunity to use federal spending to address longstanding social and economic challenges in a way not seen in a half-century. Officials said that, if approved, the spending in the plan would end decades of stagnation in federal investment in research and infrastructure—and would return government investment in those areas, as a share of the economy, to its highest levels since the 1960s.

But he’s after something bigger yet: “to prove democracy works” by using government to address public needs that private enterprise cannot—at an overall cost, when one combines the two proposals, of roughly $4 trillion.

Biden’s proposed means of financing is widely popular: increased taxes on corporations and the wealthy—an investment in our shared prosperity by the sole beneficiaries of Trump’s budget-busting tax cuts. Unsurprisingly, and cynically, congressional Republicans adamantly oppose raising taxes, even as they decry more deficit spending.

The nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates that Biden’s infrastructure plan is deficit-neutral over 15 years, and would reduce deficits in the long term. No matter. While Biden must engage the GOP in a notional search for bipartisanship, it’s clear that—as with his stimulus bill—no congressional Republican will support anything resembling his $2 trillion plan.

Once again, Biden will need the unanimous support of Senate Democrats to pass this program through budget reconciliation, and he has but three votes to spare in the House. Ignoring reality, restive progressives suggest his plan should be larger; worried centrists want the cover of bipartisan support; a few blue-state moderates demand revocation of the $10,000 ceiling on federal deductions for state and local taxes—a gift to the affluent which undermines the spirit and substance of Biden’s tax proposal.

Soon enough, Biden must persuade congressional Democrats to pull together and place their money on the table, betting that his infrastructure plan will prove as popular as his stimulus. Here’s reality’s bottom line: Democrats must have the guts and vision to break the filibuster, pass H.R. 1, and enact legislation that transforms our economy. Biden is giving them an existential choice—remake history, or let it run them over.