Cancel Envy

How an Amazon glitch helps explain the ways our siloed information environments reinforce our persecution complexes.

Here’s a weird thing that happened this weekend.

I was looking at Amazon’s app on my phone to see if The Underground Railroad, the new Amazon series directed by Barry Jenkins, was out yet. Oddly, there were no results for it when I searched. No word on when it would be released. It just . . . wasn’t there. I googled it and the first thing that popped up was an ad that took me to its Amazon landing page.

“Weird,” I thought. I shrugged and moved on, searching next for the 4K Blu-ray of Apocalypse Now.

I’d looked for it last week, seen it was $18, and decided to hold off. But with the wife headed out of town, I figured “OK, I’ll have three hours to kill one night next week.” So I looked again—and there it was. But it was now forty-some-dollars plus another four dollars in shipping. Huh. So I googled it to see what the price was elsewhere and, what popped up but a link to the original Amazon listing at the original price I’d seen a few days before.

“Weird,” I thought. “Very weird.”

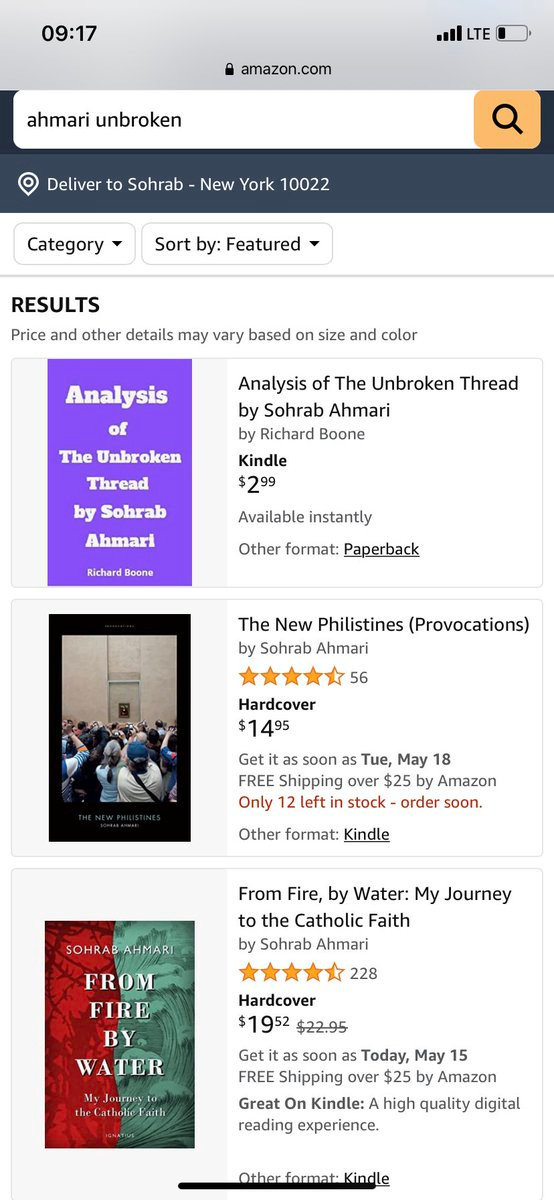

At first, I thought maybe Amazon was trying to nudge me into paying more for something, but that didn’t make sense given the fact that the company’s own prestige drama was totally hidden. So I took to Twitter and noted something was screwy with Amazon’s search function, leading to a brief conversation with a handful of folks about the generally terrible quality of Amazon’s search function and its declining reliability. I didn’t think too much of it. Until, a bit later, someone tagged me into a thread in which the New York Post’s Sohrab Ahmari suggested his new book was being blacklisted by Amazon because he’s a critic of big tech:

Now, obviously, I didn’t think that was the case. Indeed, it seemed pretty clear to me that wasn’t the case given the completely apolitical nature of the glitch I had documented earlier. But I quickly realized there was an entirely different information ecosystem that not only thought Ahmari was correct but was duplicating his result by highlighting all the other conservative books that were supposedly being shadowbanned by Amazon. J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy had been disappeared. Chaos Monkeys, written by a tech entrepreneur recently fired by Apple for being too outré, was gone. Coming Apart, Charles Murray’s book, had been condemned to the memory hole.

A few people tried to set the record straight—calmly explaining that the books’ Amazon pages were still reachable when googled, that the books were appearing as normal in the search results on Amazon’s international sites, and that the company, when asked, copped to having technical difficulties—but they were drowned out by the dudgeon. Outrage mounted as discoveries of new “banned” titles were retweeted. A few people, certain that they were observing a purge in real time, started putting together comprehensive indexes of prohibited books. Some authors may even have relished the attention brought by the controversy (who knows how many sales you can rake in from the claim that “Big Tech and Bezos are at war with my ideas”?).

I can’t say I blame these folks for thinking something nefarious was going on; after all, this comes on the heels of Amazon actually banning from its site Ryan T. Anderson’s book about the transgender movement. Even after it was clear that non-conservative books—titles by Barack Obama and Ta-Nehisi Coates and Jake Tapper, for example—were among those affected by the problem, some conservative critics continued to insist that they had been justified in leaping to conclusions about Amazon.

But the funny thing is that the exact same conversation was simultaneously happening on the left. The anti-Israel blog Mondoweiss darkly mused that Palestinian voices were being silenced in an effort by Amazon to shore up the Zionist entity. They asked their readers to send more examples and, sure enough, more examples came.

Again, this all seems to be a rather generic tech snafu. What interests me is the echo chamber effect that, on both the right and the left, quickly created a narrative of oppression and victimhood designed to engender sympathy for a preferred cause.

In a typically long essay for his Substack, Scott Alexander wrote last week about the old blogosphere and social media’s transition from a debate culture to an echo culture, one in which arguments were dismissed in favor of agreement. “Gradually throughout the 2000s this transitioned to ‘echo culture,’ where people hung out in ideologically sorted communities and discussed things from a shared perspective,” Alexander wrote. “At its worst, this was straight outrage culture. . . . But at its best, it was about building communities of likeminded people, having a space where you felt safe expressing yourself, refining shared views, and letting off steam.”

This passage came to mind while reading Ben Smith’s excellent essay highlighting the complete and utter insanity of a private Facebook group run by winners of Jeopardy that, having seen a winner flash a “three” before attempting to win his third straight Jeopardy game, decided this was a white-supremacist symbol, and tried to ruin the guy’s life.

The whole thing is worth reading—there’s a very amusing part where, informed by the Anti-Defamation League that the symbol is not a white power gesture but is in fact just the number three, a Jeopardy winner declares they are being gaslit, a term desperately in need of retirement—but this passage in particular is important:

Several members of the group who thought the reaction to Mr. Donohue’s hand was “unhinged,” as a 2020 contestant, Shawn Buell, told me, stayed silent. Mr. Buell said he assumed he would be shouted down. (He said he had initially considered membership in the group “an honor,” but had learned to stay silent this January after group members bitterly condemned the “Jeopardy!” icon Ken Jennings for defending a friend, immortalized on Twitter as “Bean Dad,” after the man tweeted about not letting his young daughter eat until she learned how to open a can of beans.)

Again, what’s interesting is not that a handful of Jeopardy winners got trolled by pranksters on 4chan into thinking the number three stands for white power. What’s interesting is the fear that Buell had about speaking up, the worry that he’d be shouted down or condemned as a racist. What’s interesting is the creation of a siloed information environment in a nominally apolitical space that echoed and amplified a particularly nutty idea until the group was convinced the ADL was in on an anti-Semitic plot.

We have built echo chambers that perpetuate falsehoods and designed defenses to keep the truth out. It’s why you’ll occasionally hear from people who are convinced that Florida officials are faking COVID data to make the state look better (they aren’t) or that Joe Biden is trying to ban meat (he isn’t). And it’s why people will dismiss the first link because it was published in National Review, the second because it was published in Politico, and this whole piece suggesting Amazon’s search bug had no nefarious intent because I write for the Washington Post. It’s why people will angrily reply to you with the relatively rare images of actual white supremacists flashing the “OK” sign if you note that the vast majority of people who use the “OK” sign are not, in fact, white supremacists. It’s why people will search for books they like to see if they have been shadowbanned rather than books they don’t like to see if they have been shadowbanned.

We’re all committed to our priors and we’ve done a great job of building up silos for ourselves—comfortable places that echo and amplify our opinions. But the thing about a silo is that it radically restricts your vision of the world. And we’re all better off when we can see a little more of it.