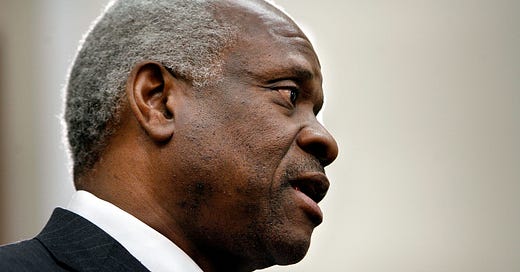

Clarence Thomas’s Flimsy Defense

Newly filed revisions to financial disclosure forms give a sense for the tactics the embattled justice is using to defend his legacy.

LAST WEEK, SUPREME COURT JUSTICE Clarence Thomas, following a ninety-day extension, filed a yachtload of corrections in his financial reporting forms for 2022 and previous years.

The accompanying six-page statement from his lawyer, Elliot S. Berke, deserves scrutiny because of the strategy it adopts: that the best defense to an embarrassing story is a good offense.

Berke goes full Trump. He attempts to convert Thomas, who made the errors, into a victim of his critics’ “hatred for his [conservative] judicial philosophy.”

See, it’s really “left wing organizations” and “left wing ‘watchdog’ groups” that are to blame for Thomas’s woes. How could they stoop so low as to criticize a poor Supreme Court justice?

To this former prosecutor’s eye, Thomas’s excuses fall fairly neatly into four buckets of classic defenses that experienced prosecutors run into—and each has an easy rebuttal.

Before getting to the four flawed defenses, it’s important to emphasize: Thomas stands accused of no crimes. Rather, it’s his reputation and his legacy that are at stake.

Berke’s casting of blame is likely intended to distract our attention from his client’s repeated failures to properly disclose things he’d evidently rather that the public not know.

For example, he’s now admitted that he failed in his 2015 form to report the prior year’s sale to his benefactor, Harlan Crow, of Thomas’s mother’s home, as was first reported back in April by ProPublica.

Thomas’s newly amended form for 2022 also reports three plane trips on Crow’s private jet and one stay at the conservative billionaire’s rustic Adirondack lodge.

There were amendments to correct other prior omissions as well.

HERE ARE THE FOUR criminal defenses echoed in the excuse-making by Thomas and his lawyer.

1. The ‘lack of willfulness’ defense: Thomas’s lapses were “inadvertent,” Berke writes, not intentional.

In other words, It was just an oversight when my client failed to disclose the sale of his mom’s house to the guy who regularly treats him to private air flights and vacations.

That’s a tough sell in the court of public opinion, as it would be in a court of law.

Especially for a Supreme Court justice who is paid to read rules correctly.

And where there was more than a little self-interest to hide: Along with the cash to the justice, the sale transferred to Crow Thomas’s mortgage and tax payments and may have allowed his mom to live rent-free with significant home improvements apparently paid for by the billionaire.

2. The ‘justification’ defense: The law recognizes that some prohibited acts reflect social values such that the acts should not be punished. Like when a severely abused spouse shoots her partner.

Thomas’s lawyer implied that his client shouldn’t be publicly criticized for having friends who “happen to be wealthy.”

That’s rich, indeed. Crow just “happened to” have befriended Thomas after he joined the Court.

At bottom, though, it’s not the friendship that raises the ethical concerns, it’s the free private flights and lavish yacht trips. When bought and paid for by others, they should be disclosed.

Especially if, as Fortune reported, Crow actually had business before the Court.

3. The ‘necessity’ defense: This is the I had to do it to avoid a greater harm defense—for example, I had to shoot the burglar who drew a knife on me.

Thomas’s corrected disclosure form now offers this necessity defense of his private flying: “Because of the increased security risk following the Dobbs opinion leak, the May [2023] flights were by private plane for official travel as [Thomas’s] security detail recommended noncommercial travel whenever possible.”

It looks like the guy who promotes himself as loving Walmarts and RVs felt a need to explain that it wasn’t a matter of taste for luxury and privilege, but rather of necessity that he flew privately.

But this defense doesn’t fly: What about all those Gulfstream trips before May 2022, when the purported necessity hadn’t yet arisen?

4. The ‘mistake of law’ defense: In some circumstances, a mistake of law can be a valid defense. For example, an accused person may show that he reasonably relied upon a legal “interpretation by an applicable official.”

Thomas notes on his new amended form that in 2006, the Judicial Conference advised Judge Raymond Randolph that private flights needn’t be disclosed based on the Ethics in Government Act’s hospitality exemption.

But are the facts of Judge Randolph’s case and Justice Thomas’s the same? Did Randolph’s gift come from someone whose company had appeared before him in court?

In any event, the “hospitality” exemption states that gifts of “any food, lodging, or entertainment received as personal hospitality of an individual need not be reported.” “Hospitality” is defined as gifts given “for a nonbusiness purpose . . . at [an individual’s] personal residence . . . or on property or facilities owned by that individual.”

That “lodging” portion of that exemption, apparently, was also the basis for Thomas not reporting his complimentary vacations on billionare-owned yachts.

But there is much here we still don’t know. For example, Thomas’s amended form says that he reported as “reimbursements” his 2022 trip to and stay at Crow’s Adirondack lodge because of a change of policy according to private advice given by the Judicial Conference staff in July.

But since Thomas doesn’t quote that advice or tell us what it was, we don’t know whether his implication—that he had been under no obligation to report the trip under the previous guidance—is correct.

Stay tuned. We’re almost sure to find out more about that July 2023 staff advice.