C’mon C’mon occasionally feels a bit more like a visual and auditory essay than it does a traditional feature film. The film’s narrative sees radio journalist Johnny (Joaquin Phoenix) care for his nephew Jesse (Woody Norman) while Jesse’s mother Viv (Gaby Hoffman) tries to convince the boy’s bipolar father Paul (Scoot McNairy) to commit to psychiatric treatment. But this is intercut with a series of interviews between Johnny and schoolchildren across the country, as well as snippets from essays and children’s books read aloud by Johnny.

What Mike Mills has put together in C’mon C’mon calls to mind longform journalism of the sort practiced by a David Foster Wallace or a Matt Labash: empathetic and occasionally discursive, though always driving toward a deeper truth. Except, of course, that it’s fiction, not fact. But the best fiction reflects reality on some level, so who’s to say that the distinction between fact and fiction is all that important when there are deeper truths to plumb. “Fake but accurate” has nothing on “fictional but true.”

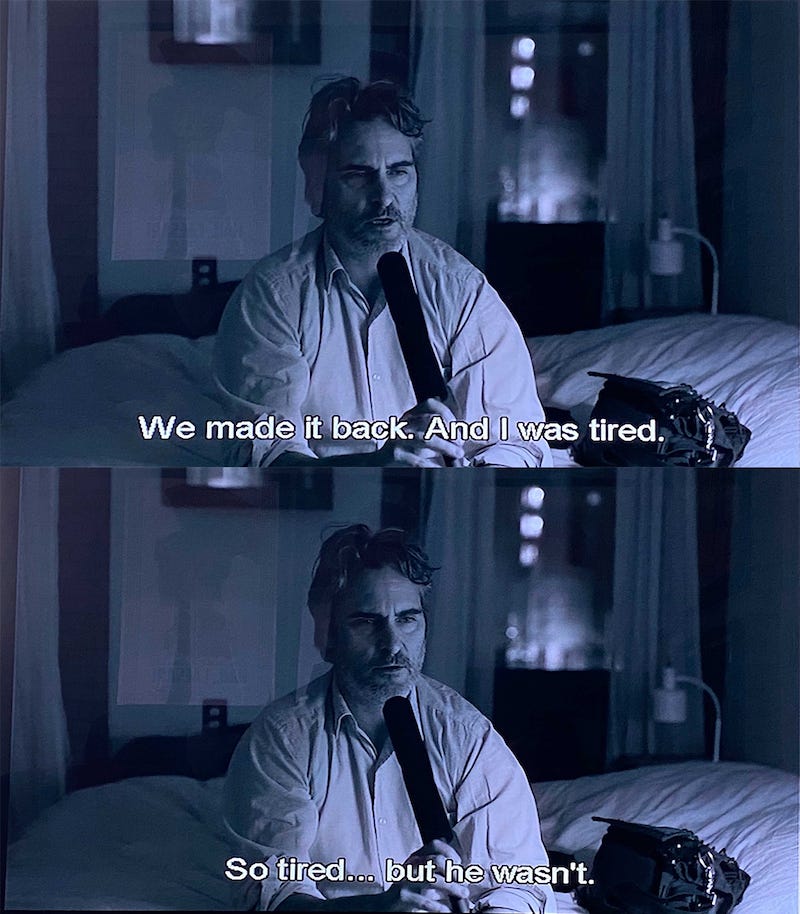

But that truth would be elusive without the magnetic, powerful, and sometimes uncomfortable naturalism of Phoenix, whose work as Johnny is sublime and subtle. Johnny is thrown into the deep end by Viv, being asked to watch a precocious youngster despite having no kids of his own and no history of minding children. At one point, Johnny, speaking into a recorder that doubles as a diary and recounting the day’s activities, says “We made it back. And I was tired. So tired … but he wasn’t.”

This is one of these simple, quiet truths that will cause any parent in the audience to exhale sharply while unconsciously nodding their head. That feeling of exhaustion in the face of boundless energy, an energy that only reminds you of how much slower you are, how much less you have to give the world, how much you need everything to just calm down for a minute so you can close your eyes and relax and not have to worry about this tiny dynamo with legs dying because he walked off into traffic when you looked away: It’s real, man. It’s as real as it gets.

You see that exhaustion in Phoenix, in his eyes, in his posture, a sort of thousand-kid stare combined with a slouch and a paunch that all just screams “put me to bed, please.” But there’s joy in the exhaustion too, as when Johnny and Jesse are verbally sparring, testing each other, seeing how far to push. Johnny spends his times interviewing kids for some manner of project or other—the desire not to displease donors necessitates bringing Jesse from Los Angeles to New York to New Orleans—and like all good interviewers he’s a good listener, but there’s something different about listening to a kid you live with, trying to understand what he actually wants and needs, as opposed to planning your next query.

As with most actors, Phoenix probably gets more attention for his eccentrics—winning an Oscar for his Joker and garnering nominations for a cult follower in The Master, Johnny Cash in Walk the Line, and Commodus in Gladiator—than his regular guys. It is often the most acting that nets the most praise. But he and Mills have crafted a beautiful portrait of normal life in all its simplicity and sadness and silliness.

This review will discuss plot points for The Power of the Dog, including the end.

There is a monster at the heart of Jane Campion’s The Power of the Dog, but I do not think the monster is the character everyone else seems to think it is.

Phil Burbank (Benedict Cumberbatch) and his brother George (Jesse Plemons) are ranchers, having spent 25 years driving cattle together. Phil is casually cruel, repeatedly referring to George as “fatso,” denigrating his intelligence, insulting his manliness. Masculinity is very important to Phil; he reacts with something akin to revulsion while being served by Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee) at the restaurant operated by his mother, Rose (Kirsten Dunst).

Peter is a sensitive soul; he makes paper flowers as place settings and is quite fastidious in his appearance, preferring white tennis shoes to the cowboy boots of others in their Montana community. Everything he does onscreen is coded as “queer,” from his gait to his manner of dress, and almost comically stereotypically so: For instance, at one point, after being insulted, Peter goes outside and starts hula-hooping. He’s thin, bird-like, fussy.

After Rose marries George, Peter and his mother are forced into close contact with Phil, a proximity that sets Rose to drinking. She’s overly protective of her son and doubtful of her own talents as a wife and homemaker. She can’t even play the piano better than the domineering Phil can play the banjo—and given that Phil’s a Yale man with a degree in classics, she’s probably not going to out-debate him, either.

But as the film progresses we come to realize that Phil is fighting back urges of his own. And he takes young Peter under his wing, teaching him to ride, trying to toughen him up so he can survive in a world that both hates and fears him. This effort at friendliness is repaid at film’s end with murder.

Now. Here’s where I think things get a bit interesting. Everything Campion has done throughout the movie is designed to earn Peter our sympathies and Phil our disgust. Phil is sneering, he insults the help, he slaps horses on the nose when he’s angry with his brother, he insults Rose. Hell, he’s literally dirty, refusing to bathe before a dinner with the governor. He is a walking, talking avatar of the dread toxic masculinity.

And yet, he is not the film’s monster. No, this film’s monster recalls another film’s monster. Peter’s a gangly, awkward, bird-like man smothered by his mother’s affection who turns to murder when that mother is threatened; I don’t know that Smit-McPhee was channeling Anthony Perkins in this performance, precisely, but there are strains of Psycho throughout, down to the opening lines: “When my father passed, I wanted nothing more than my mother’s happiness. For what kind of man would I be if I did not help my mother?” In the film we see Peter progress from animal mutilation (tw: bunny evisceration) to human murder. If this isn’t the origin story of serial killer, I don’t know what would be.

My friend Victor Morton, in panning The Power of the Dog, asked the following: “What on earth does it mean for a member of the intellectual classes to ‘demystify’ or ‘subvert’ tropes that nobody in the intellectual classes believes any more”? I take his point—if The Power of the Dog is intended to deconstruct the dread toxic masculinity, it fails, as there’s nothing quite this obvious left to be said on the subject—though I can’t help but feel as if Campion is getting at something slightly different.

What if she is, rather, asking how much we, the audience, will excuse when we are predisposed to sympathize with the perpetrator of a horrible crime?