Want to Be President? Take a Cognitive Test.

The need is clear. Here’s how mental-fitness tests could be implemented.

JOE BIDEN AND DONALD TRUMP have together made one thing abundantly clear: It’s time to seriously consider mental wellness checks for presidential candidates. As the Constitution and federal law now stand, there’s probably little Congress could do about a mentally unstable sitting president. But Congress, state legislatures and party leaders could take steps to require candidates for president to pass the same kinds of mental health standards that airline pilots do. The safety of the American people demands it.

Two necessary caveats up front: First, I’m not a physician, a neurologist, or a geriatrician, but a legal commentator who in recent years has shared the widespread concerns of observers from across the political spectrum. And second, mental wellness and aging are very complicated, and the processes involved often occur in unpredictable, episodic, inconsistent, and unobvious ways. A person might struggle with some tasks one day and not the next, or in one setting but not another.

Still, most of us would probably agree that good physical and mental health are important for the weighty job of president of the United States.

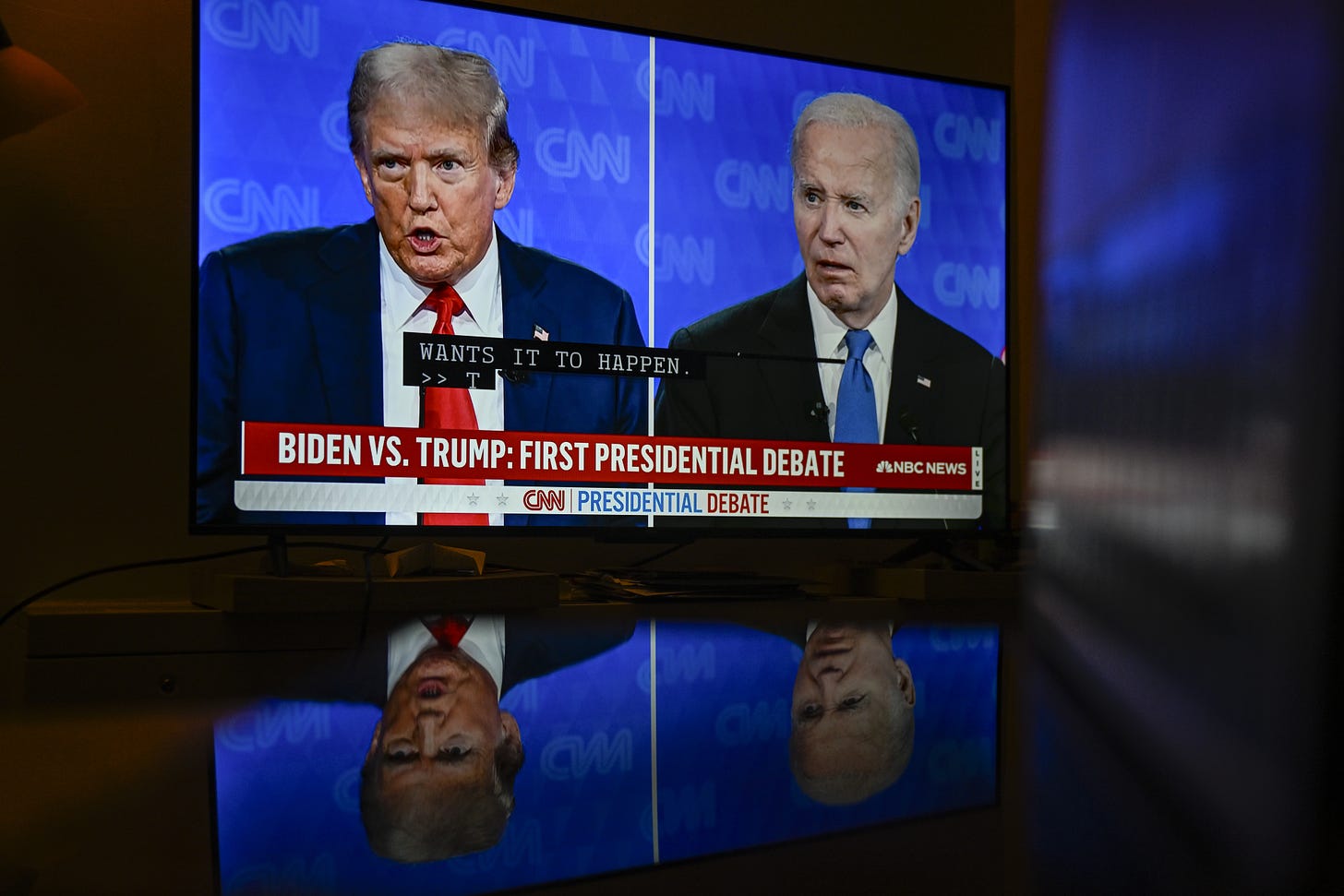

President Joe Biden’s cognitive health became the subject of relentless media coverage following his stumbling performance during his June 27 CNN debate with former President Donald Trump—and ultimately led him, under pressure from his fellow Democrats, to step aside as his party’s nominee for president.

The press has been far more forgiving of Trump’s non sequiturs, disjointed rambling, lies, malapropisms, and solecisms, largely refusing to treat them as indicators of cognitive decline, although stories and speculation about Trump’s mental instability have circulated for years. In 2018, an anonymous official inside the Trump administration (later revealed to be Miles Taylor, chief of staff to Secretary of Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen) wrote an op-ed for the New York Times revealing Trump’s dangerous impetuousness, stating that he “engages in repetitive rants, and his impulsiveness results in half-baked, ill-informed and occasionally reckless decisions that have to be walked back.” The anthology, The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump, with essays about Trump from dozens of psychiatrists, psychologists, and mental health professionals, was a bestseller when the first edition come out in 2017.

It was also in 2017, following the firing of FBI Director James Comey, that Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein reportedly floated the possibility of invoking the Twenty-fifth Amendment to address Trump’s unfitness for office. That amendment states that if the vice president and a majority of cabinet secretaries decide that the president is “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office,” they can alert the speaker of the House and the Senate’s president pro tempore and the vice president immediately becomes acting president. But the Twenty-fifth Amendment was really designed to address physical incapacity—not mental unfitness—and allows presidents to fire back to Congress that “no inability exists.” Such ping-ponging would rapidly devolve into partisanship.

In 2019, 350 mental health professionals signed a letter to Congress warning that Trump’s mental health was dangerously deteriorating, making him “a threat to the safety of our nation.” This past May, John Gartner, a psychologist and former assistant professor at Johns Hopkins University Medical, suggested that Trump suffers from three separate mental health disorders: malignant narcissistic personality disorder, hypermanic temperament, and dementia. The hypermania, Gartner suggests, would account for his frantic, rage-filled Truth Social postings.

BIDEN AND TRUMP ARE NOT THE FIRST PRESIDENTS whose mental health posed potentially serious problems to the welfare of the nation. President Woodrow Wilson’s extreme incapacity following his October 1919 stroke was largely hidden from the public for months, then became a subject of intense debate.

Biographers report that President Franklin Roosevelt’s physical decline in his final years in office affected his mind; he had difficulty concentrating and would sometimes blank out, and toward the end he was forced to husband his strength and required long periods of recuperation following exertions.

President Ronald Reagan’s staff briefly and very hypothetically contemplated using section 4 of the Twenty-fifth Amendment as the White House became relatively chaotic late in his presidency. Reagan was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 1994, five years after leaving office; the extent to which he showed symptoms while in office remains debated, although there were public and private displays of confusion, memory lapses, and other behaviors associated with aging. The accounts from Reagan’s physicians, who repeatedly affirmed his mental health until 1994, sound a lot like the reports from Dr. Ronny Jackson, Donald Trump’s White House doctor, who still consistently praises Trump’s health.

A 2006 analysis of presidential biographies by physicians at Duke University Medical Center found that roughly half of the country’s first 37 presidents (spanning 1776–1974) seemed to have some form of mental illness at some point in their lives; more than half of those were afflicted while in office. Such historical-biographical diagnoses of long-dead individuals should be taken with a grain of salt, or maybe a whole shaker-full, but the findings are intriguing: According to the authors, 24 percent of those presidents apparently suffered from depression (including James Madison, John Quincy Adams, Franklin Pierce, Abraham Lincoln, and Calvin Coolidge); 8 percent seemed to have had anxiety disorders (including Thomas Jefferson, Ulysses S. Grant, Coolidge, and Woodrow Wilson); and another 8 percent showed signs of bipolar disorder (including Lyndon Johnson and Theodore Roosevelt). Still another 8 percent abused alcohol (including Franklin Pierce, who died of cirrhosis of the liver, and Ulysses S. Grant, who was so intoxicated during a parade in New Orleans that he reportedly fell off his horse).

OF COURSE, A DIAGNOSIS of some sort of mental health disorder is hardly disqualifying for the presidency. One does not have to be a mental health professional to appreciate the big difference between anxiety or depression on one hand and schizophrenia or psychopathy on the other, for example. Some mental health disorders improve performance at certain tasks. And narcissism could be a common denominator for those who seek unparalleled political power.

Experts know the difference. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), for example, requires airline pilots to undergo a medical exam with an aviation medical examiner every six months to five years, depending on their jobs and their age. A comparable sort of test should apply to presidential candidates so voters know what they’re getting themselves into. For example, aviation medical examiners can deny or defer approval of aviation candidates who have psychosis, substance abuse or dependence, or a history of suicide attempts. The FAA has also determined that neurocognitive impairments like head trauma, stroke, encephalitis, and multiple sclerosis “would make the airman unsafe to perform pilot duties.” The job of president is not the same as piloting an airplane, but in both cases pathologically impaired judgment can affect the lives of other people—arguably even more drastically for presidents than for pilots.

Figuring out how actually to impose such a fitness test as a matter of law is an entirely separate problem.

The Constitution contains only a handful of criteria for president, such as age, U.S. citizenship, no prior disqualifying conviction following impeachment, and no engagement in an insurrection (wait . . . scratch that, the Supreme Court just deactivated that requirement for Trump this spring). If Congress were to attempt to impose additional mental health criteria on presidents, the Supreme Court would likely strike them down.

But the Federal Election Commission could request background checks as part of its requirements for declaring a candidacy for president and include fines if candidates fail to cooperate, and those background checks could touch on matters of mental health.

Or the two leading political parties could make candidates undergo such background checks as a prerequisite for, say, participating in primary debates.

Candidates must also satisfy a complex range of filing requirements and deadlines under state law in order to run for president, and states could make taking a mental-fitness test an optional addition to that list of requirements. States cannot add to the constitutional prerequisites for presidents any more than Congress can, so in all likelihood it cannot be a mandatory test—yet if a candidate declines to participate in the optional mental-fitness test, that refusal could become a political issue that voters would be able to bring to the ballot box. For now, the type of information such a test would reveal is either speculative and unsubstantiated, hyperbolic, potentially false, or hidden from public view.

This round, it’s clear that millions of Americans don’t care that Trump is ostensibly mentally unfit to be president. Neither do the leaders of his party. But if American democracy winds up surviving this existential jousting, the public should demand that measures be put in place to avoid allowing mentally unstable or cognitively unwell people to sit behind the most powerful desk in the world ever again.