Congress Passes Historic Bill Making Lynching a Federal Hate Crime

After hundreds of attempts across more than a century, a federal antilynching bill now awaits the president’s signature.

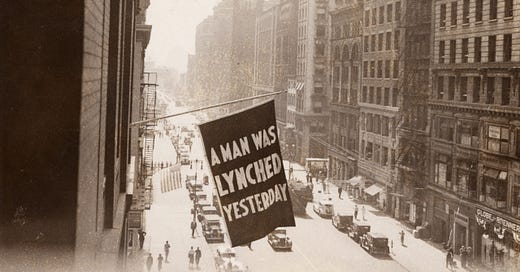

Yesterday, Congress accomplished something that it has failed to do over the course of our nation’s history: After nearly 250 attempts going back 122 years, it passed a bill making lynching a federal crime.

Last Monday, the last day of Black History Month, the House of Representatives passed the Emmett Till Antilynching Act by 422 to 3. The Senate followed last night, passing the bill by unanimous consent.

It is a remarkable fact, given the American history of mob violence directed at people because of their race or ethnicity, that there has never been a person federally convicted of the crime. Once President Joe Biden puts his signature on the bill, lynching will join the other acts defined as hate crimes under federal law.

The path to this historic day was long and winding and littered with intransigence.

Two years ago, the last attempt at passing a version of this bill was blocked by Senator Rand Paul (R-Ky.), who declared that that version contained unnecessarily broad definitions of lynching. He pointed, for example, to a provision that suggested that conspiring to damage religious property or intimidating someone attempting to vote would qualify as lynching. He defended his position, saying, “I think that’s a crime to deface a church, but if you were one of the Black Lives Matter folks at Lafayette Square and you painted ‘BLM Forever’ or something on a church, that could be considered lynching under this bill.”

His concerns were addressed: Paul joined the three black sitting senators—Republican Senator Tim Scott and Democratic Senators Cory Booker and Raphael Warnock—in cosponsoring the version that just passed. In a statement, Paul said he was pleased “to strengthen the language of this bill, which will ensure that federal law will define lynching as the absolutely heinous crime that it is.”

The first congressional attempt to pass antilynching legislation came in 1900. More than 1,100 black Americans had been lynched in the previous decade (as well as more than 400 whites). But when Rep. George Henry White, a black Republican from North Carolina, introduced an antilynching bill, white segregationist Democrats blocked it in committee. In 1918, when there was not a single black American in Congress, Missouri Rep. Leonidas Dyer introduced an antilynching bill that four years later passed the Republican-controlled House. But it was promptly filibustered in the Senate by white segregationist Southerners who declared the matter an issue for the states and not the federal government.

President Franklin Roosevelt, to the displeasure of his wife Eleanor and the black leaders who met with him, did not back a 1935 effort for fear of losing white votes in the South.

In 1955, Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy from Illinois, was lynched in Mississippi after being accused of using vulgar language toward a white woman—a woman who later admitted she made the whole thing up. His extremely brutal and public lynching further energized the civil rights movement. But it did not compel Congress to act on antilynching legislation.

All told, antilynching bills were introduced hundreds of times in Congress, and they always failed. Until now.

Some commentators have argued that the antilynching bill isn’t necessary—not because they agree with the segregationists from a century ago but because they argue that lynching is already illegal. Indeed, Paul made this assertion in 2020. Murder is a crime in all fifty states; nearly all states have laws on the books criminalizing race-based violence; and the revision of federal hate crimes statutes in 2009—with the passage of a bill named for James Byrd Jr. and Matthew Shepard—clarified the ways in which racially motivated violence can be prosecuted as a federal crime. What then, opponents ask, is the point of passing this new bill focusing specifically on lynching?

The Emmett Till Antilynching Act defines lynching as the conspiracy to commit a hate crime that results in death or serious bodily injury and carries a penalty of not more than 30 years in prison. It is the “conspiracy” aspect of the crime that distinguishes it textually from other hate crimes.

But more than that, naming the crime in federal law carries tremendous weight, both legal and social. As I have written previously, it matters that people who violently assault Asian Americans or Jewish people are charged with hate crimes and not just assault. It matters that we can convict people of terrorism instead of just mass murder. And it matters that the three men who followed Ahmaud Arbery, accosted and detained him, and then killed him were charged with federal hate crimes, but could not be charged with lynching. The social stigmas and penalty associated with being a terrorist or a lyncher are meaningful and a declaration of a society’s values and norms. For a nation with our history, the importance of this legislation extends far beyond the letter of the law.

Democratic Rep. Bobby Rush, who introduced the bill in the House, said after its passage, “Today is a day of enormous consequence for our nation … the House has sent a resounding message that our nation is finally reckoning with one of the darkest and most horrific periods of our history, and that we are morally and legally committed to changing course.” Last night, Sen. Tim Scott, who has sponsored multiple attempts at antilynching bills, said upon the bill’s passage in that chamber, “Tonight the Senate passed my anti-lynching legislation, taking a necessary and long-overdue step toward a more unified and just America.”

We should be proud of our country today. Our generation has managed to do something previous generations neglected or could not manage. By squarely facing the ugliness of lynching—the horror of the violence and the oppressive fear it created—and declaring it incompatible with who we now are as a people, we have revealed a little more of the beauty in the nation’s progress.