The COVID-19 Revisionists Are Twisting the Record

Lockdown skeptics and mask critics are crowing—and distorting what happened five years ago.

AS WE PASS THE FIVE-YEAR ANNIVERSARY of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic—the World Health Organization’s pandemic declaration, the Trump administration’s declaration of a national emergency, and the first statewide lockdown orders all happened in mid-March 2020—there is an understandable interest in looking back to reassess our collective response to the disease that has killed more than a million Americans and upended everyone’s lives. The New York Times recently ran a column by Princeton professor Zeynep Tufecki harshly criticizing scientists who downplayed the virus’s possible origin in gain-of-function research at the Wuhan laboratory. The Boston Globe has run a feature showcasing researchers who believe the COVID lockdowns were harmful. Vox science writer Kelsey Piper, one of the first journalists in 2020 to urge taking the danger of COVID more seriously, has called for a “reckoning” for errors such as extended school closures—while admitting her own mistake in dismissing the “lab-leak” hypothesis as a conspiracy theory.

Reassessments, reckonings, and admissions of error are good. Unfortunately, as Piper notes, the political polarization of everything related to COVID-19 makes such conversation very difficult: It can be easily hijacked to promote a revisionism that not only distorts the facts but fuels animosity toward “conventional” medicine and legitimizes anti-science cranks. That’s especially concerning when the father of all cranks is at the helm of the Department of Health and Human Services.

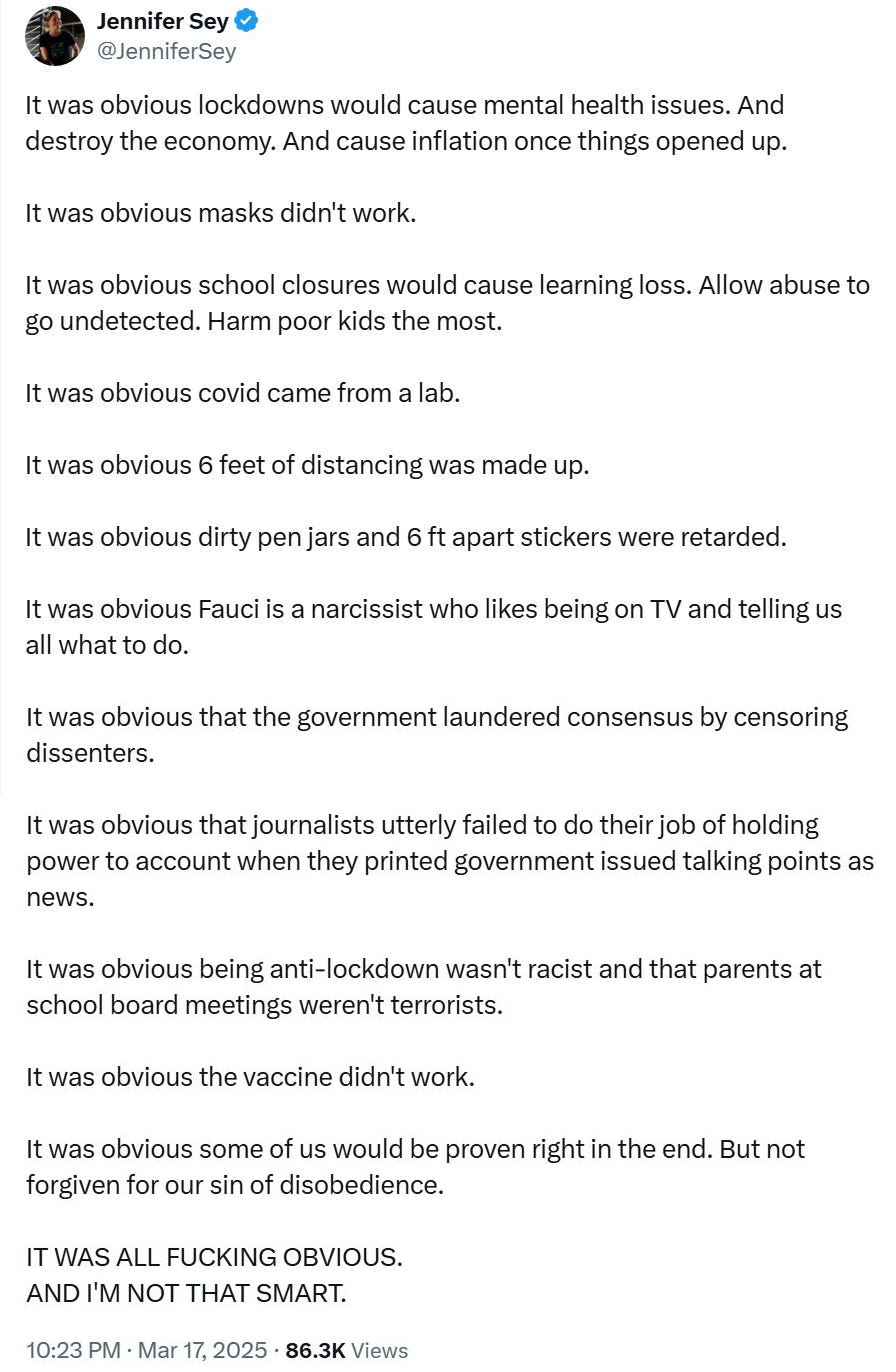

Take pro-MAGA entrepreneur Jennifer Sey’s tweet treating Tufecki’s column on the lab leak theory as a sweeping vindication of the opinions of the COVID “dissenters” on everything from masks to vaccines to social distancing measures to Anthony Fauci:

In fact, COVID debate is hardly new. The lab-leak theory, dismissed by the initial consensus and even briefly banned as “misinformation” on Facebook, was widely discussed and defended by the summer of 2021. (It should be noted that the lab leak theory is by no means proven correct, and many leading experts in the field, such as University of Sydney virologist Edward Holmes, a top authority on viral evolution, still regard it as unfounded.) The reopening of schools was robustly debated in the fall of 2020; Fauci supported it except in districts experiencing COVID outbreaks (which derailed some reopenings in red states). By 2022, there was widespread agreement that extended school closures had been harmful, particularly for lower-income children.

But the revisionists make a much more sweeping indictment: They assert that all policies intended to curb the spread of COVID in the general population—stay-at-home orders, bans on public gatherings, nonessential business closures, masking mandates, personal-distancing guidelines, etc.—were not only useless but harmful. That view is prevalent in right-wing and “heterodox” circles; it has been gaining mainstream respectability as well. For instance, in their new book, In COVID’s Wake: How Our Politics Failed Us, Princeton political scientists Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee come down squarely on the lockdown-skeptic side.

Many medical experts, including former National Institutes of Health director Francis Collins, agree the public health establishment should have been more sensitive to the costs of lockdowns. (The unanticipated “collateral damage” includes an apparent increase in fatal drug overdoses during the pandemic’s early months.) But the lockdown skeptics go much further to claim that mitigation measures saved no lives. The arguments marshaled to support this view are often dubious. For instance, Macedo and Lee point out that longer duration of stay-at-home orders state-by-state did not correlate with lower COVID mortality—but this metric doesn’t take into account variations in population density and average age, and it ignores other mitigation measures such as restrictions on indoor gatherings. While lockdown skeptics often cite lockdown-free Sweden as a success story, one study found that Sweden’s relatively lax policies caused nearly 4,500 extra deaths in a country of about 10 million. A proportionate toll in the United States would have yielded roughly an additional 150,000 dead Americans—and probably more, since Swedes are the healthier population.

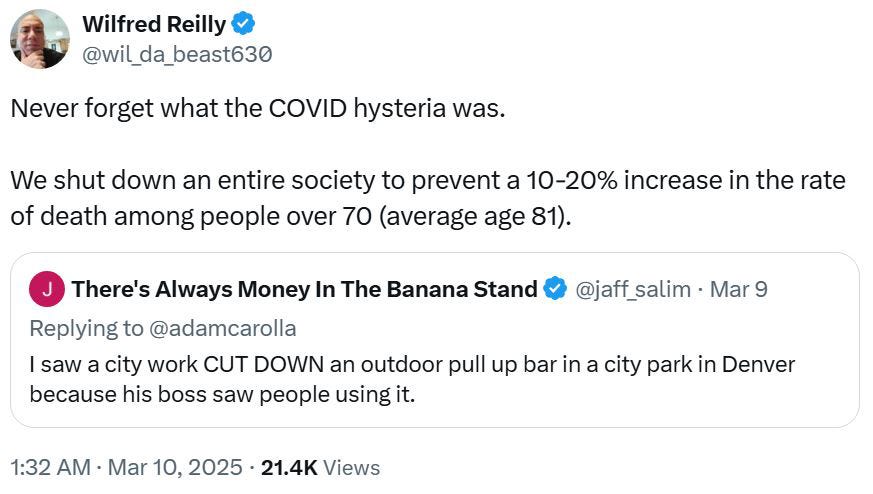

There is also the belief—espoused, for example, by conservative academic and pundit Wilfred Reilly—that even if strict mitigation measures did prevent deaths, they were still unjustified because the people who would have died were overwhelmingly old and saving them was a bad tradeoff.

Aside from the wretched morality implied in this calculus, the cold, hard fact is that in 2020, more than 40 percent of COVID deaths in the United States were among people under 75 and almost 20 percent were among people under 65. And that’s not to mention the often-severe and long-lasting health consequences for many survivors.

What’s more, just as it’s difficult to quantify how many lives were likely saved by mitigation measures, the human and economic costs of the lockdowns are often difficult to disaggregate from the effects of the pandemic itself: not only the fear of illness—for oneself and loved ones—but the stress and anguish of dealing with illness and death among family, friends, and neighbors. (Notably, one study the Boston Globe cited as evidence that “lockdown policies” had “spurred a dramatic rise in adolescent anxiety and depression” actually dealt with the total impact of the pandemic, not just the lockdowns.) The same goes for economic impact. COVID-related business closures in “free” Florida in the first year of the pandemic were only slightly below locked-down California (32.2 percent vs. 35.9 percent) and above locked-down Minnesota (26.6 percent). The economic downturn and subsequent rebound in Sweden were roughly the same as for its locked-down Nordic neighbors.

AT A FIVE-YEAR REMOVE, when both vaccination and the virus’s mutation toward less lethal variants have made COVID-19 far less scary, it’s easy to forget that the pandemic’s initial wave was terrifying for good reasons, not because of “hysteria,” hype, or panic. In my home state of New Jersey, a single family lost five members—three of them siblings in their mid-fifties—to an infection that tore through a family gathering in March 2020. In Arizona, three teachers who shared a summer-school classroom got COVID that summer; it killed one of them, 61-year-old Kimberley Byrd. Her 68-year-old brother Roy Chavez, who probably contracted the virus from her at an outdoor picnic, died three weeks later. (Both siblings had health problems—Byrd suffered from asthma and lupus, Chavez from diabetes—but that’s true of a lot of middle-aged Americans.) I knew several people in their forties and fifties who were very seriously ill; one, a health care professional not prone to hysteria, ended up in intensive care and, for more than six months after recovery, couldn’t walk up a flight of stairs without getting out of breath. And while COVID is now known—especially in its later variants—to be no more dangerous to children than the flu, early reports of an extremely dangerous COVID-related syndrome in children and teenagers could hardly be discounted.

Finally, it is useful to remember that the COVID restrictions in the spring of 2020 were not tyrannically imposed on an unwilling population: they had broad popular support. In a Pew Research Center poll in early May of that year, only 24 percent of Americans said they wanted fewer restrictions on public activity in the area where they lived while 27 percent wanted more—and 68 percent were more concerned about restrictions being lifted too quickly than not quickly enough.

Even more surprisingly, a strong majority across all ages—though with a clear partisan split—still broadly approves of the COVID mitigation strategies that were used in the first months of the pandemic. In a Pew poll last month, 44 percent of Americans said that the area where they live had the right amount of COVID restrictions while 18 percent said there should have been more. The shift toward anti-lockdown sentiment is driven almost entirely by Republicans (of whom a sizable minority, 38 percent, bucks the party line and supports lockdowns). Another poll conducted last summer for the Harvard School of Public Health found that majorities of Americans still approved of key pandemic control policies: 70 percent thought masking requirements in stores and businesses had been a good idea, 63 percent supported indoor dining closures, and 65 percent were in favor of vaccination mandates for healthcare workers. Even closures of K-12 public schools for six months or more garnered 56 percent support. The idea that the COVID lockdowns were a horrific exercise in tyranny may have currency in large swaths of the internet today, but it’s still very much a minority opinion in the real world—and was even more so four years ago.

SHOULD PEOPLE IN THE COVID-19 “mainstream” acknowledge and apologize for their errors? Self-examination and accountability are always good. But if there needs to be a “reckoning” for those who may have advocated unnecessarily harsh COVID restrictions or needlessly onerous precautions, then let’s have a little accountability for the “dissidents,” as well. Have any of them apologized for predicting that COVID would kill only a few thousand Americans? For wrongly claiming that the pandemic was basically over when it wasn’t? For pushing junk remedies like ivermectin and hydroxychloroquine? And, above all, for trying to undermine and discredit vaccination, which has unquestionably saved countless lives and has allowed millions to resume a normal life?

Spoiler: No, they haven’t. Instead, the right has been having, in Jonathan Chait’s caustic phrase, “a kind of anti-reckoning” in which holders of bad COVID opinions get rewarded with positions of power that make them look like the winners in the scientific debate. For instance, Stanford professor Jay Bhattacharya was just confirmed as the director of the National Institutes of Health; his COVID contrarianism includes the claim, in a March 2020 Wall Street Journal column, that the U.S. death toll for COVID-19 would likely end up being 20,000 to 40,000 Americans, comparable with the seasonal flu.

The double standard is obvious—and it’s a problem. As long as only the “normies” are expected and even pushed to admit their errors and failings, the “dissenters” will always use such admissions as an opportunity to cry vindication.