David Lynch, 1946–2025

“Everything is new.”

DAVID LYNCH, THE FILMMAKER, musician, and painter, died this week following a serious decline in health after evacuating his home during the Southern California wildfires. He was 78 and a heavy smoker; in recent years he had revealed that he was suffering from emphysema. The physical difficulties of his condition left little hope he would ever direct another feature or television show. Other than short films and music videos (of which there were many, to be fair), Lynch hadn’t directed anything of prominence since 2015.

That project—Twin Peaks: The Return, which was released in 2017—will now stand as a very fitting capstone to his unique career. Twenty-five years after the astonishing success of the two seasons of the original Twin Peaks television show, Lynch and co-creator Mark Frost delivered a third season that was not simply stranger than the ABC version. These eighteen episodes aired on Showtime, the pay-cable network, which meant that Lynch, never one to tamp down on his imagination, could be, and was, completely untethered. A sprawling, supernatural, cosmic, and historical phantasmagoria that nevertheless found plenty of room for grace notes both lovely and harrowing. It was an event, and, critically at least, a massive hit. The influential film magazines Sight and Sound and Cahiers du Cinéma both named this TV show among the two best films of 2017.

Lynch’s feature film career began in 1977, with the release of Eraserhead, his surreal horror film about the drudgery of existence and the terrors of sex and fatherhood. In Chris Rodley’s Lynch on Lynch, the director describes Henry Spencer (Jack Nance), the protagonist of the film, as someone who is “very sure something is happening, but he doesn’t understand it at all”:

He watches things very, very carefully, because he’s trying to figure them out. He might study the corner of that pie container, just because it’s in his line of sight, and he might wonder why he sat where he did to have that be there like that. Everything is new.

“Everything is new” is one of the keys to his films, if not the key. Those who do not connect to Lynch’s work often reject it on the grounds that much of it doesn’t make any sense. This isn’t always true—the viewer often does have to do more of the work than he’s used to—but it is sometimes, even often, true. You could walk out of one of his films, even a relatively accessible (I’m speaking very relatively here) and popular one like Mulholland Drive (2001), and wonder what in the hell you’d just seen. Even in a film set in the real world, something new, mysterious, and probably disturbing, on levels both obvious and hidden, was just around the corner, or just down that path, or just next door. And what was that thing behind the dumpster, anyway?

Mel Brooks’s production company Brooksfilms had secured the rights to two books about Joseph Merrick, an Englishman born in 1826 who suffered from a physical deformity so severe that he was first displayed in a sideshow as the “elephant man” before being removed to a hospital. On the basis of Eraserhead, Brooks approached Lynch to make his film about Joseph Merrick (named “John” in the film). Lynch was drawn to the project, and the resulting film, The Elephant Man (1980), a heartbreaking and thoroughly sincere emotional drama, began opening doors for him.

Of course, Lynch might have ultimately wished that those doors had remained closed. The first film the now-famous director was tapped to make was Dune (1984). Produced by Dino de Laurentiis and his daughter Raffaela, this adaptation of the classic Frank Herbert novel became notorious. It was a big swing, a shot at something commercially monumental, and a notorious disaster. Lynch’s Dune remains as unique and idiosyncratic as an American science fiction film is ever likely to get, at least in the ’80s. If the movie’s not entirely successful, it’s not for a lack of trying.

Lynch retreated back into his own head for his next film, Blue Velvet (1986). While Lynch, consciously or not, has always worked within established genres, Blue Velvet is perhaps the most straightforward example of him working in this mode. A dark thriller, full of twisted sex and shocking violence, Blue Velvet introduced a villain for the ages in Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper), a man so evil that the two heroes, Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachlan) and Sandy (Laura Dern), marvel in terror that such a human being could even exist, is even permitted to exist. All this while Jeffrey finds himself erotically drawn to the voyeuristic and violent sexuality of Booth’s primary victim, Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini). Frank Booth is new. Jeffrey’s desires, previously a secret even to him, are new. Again: “Everything is new.”

Twin Peaks was next. Lynch was mostly absent for the largely disappointing second season (except for the finale, which is a real barn-burner, and one of the most frightening things I’ve ever seen). ABC was pushing for the show’s central question—“Who killed Laura Palmer?”—to be answered. Believing this would end the show prematurely, Lynch removed himself and went back to films. He next made Wild at Heart (1990), a film that ramped up the sex and violence in his work, and which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes.

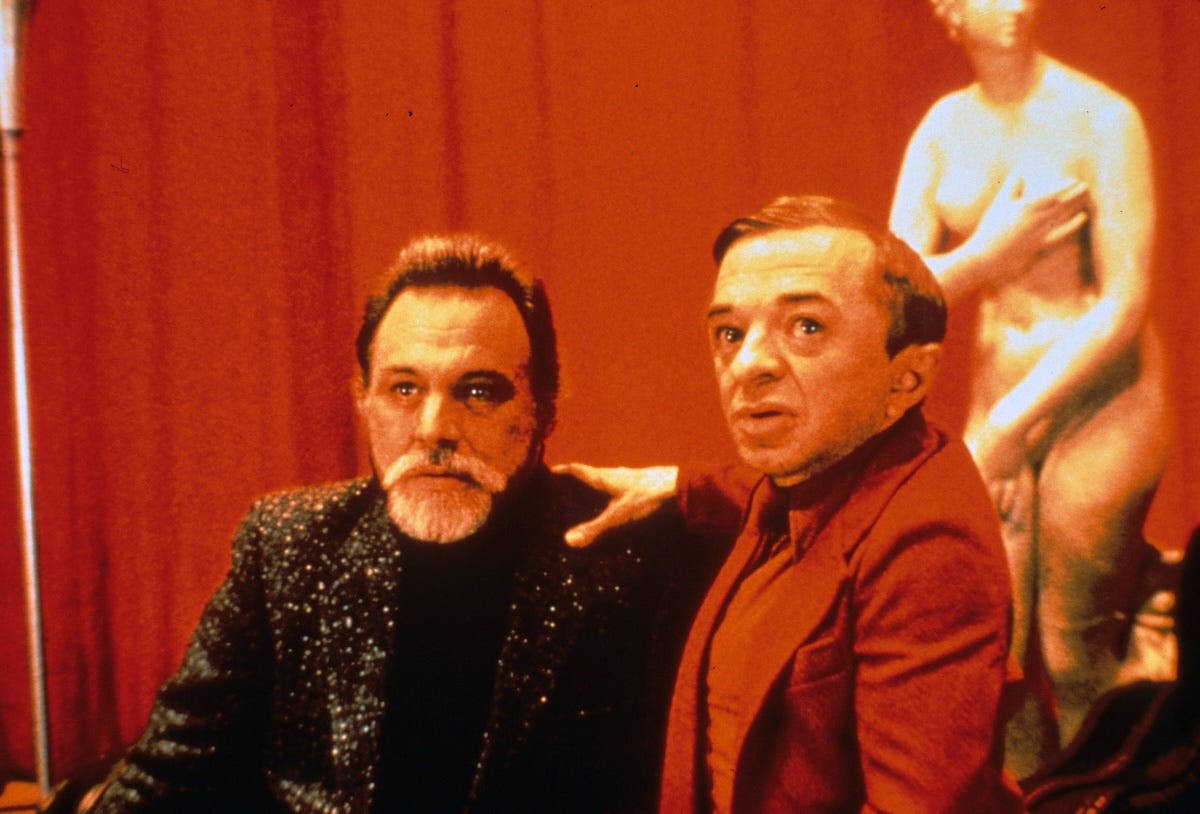

But it was his next film that, for me, best defines David Lynch. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me premiered at Cannes in 1992 and was met with howls of derision. Quentin Tarantino has said that upon seeing that movie, he pretty much gave up on David Lynch. Lynch himself has said that while he wished this feature film prequel to his iconic TV show had done better, he was satisfied with it. He blamed Dune’s failure on himself, and regretted the whole experience. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me was different, because whatever anyone else thought of it, he knew he’d made the best film he could make. I have called the film perhaps the saddest horror movie ever made, and I don’t think there’s a lot of competition for that title. Bursting with crazed imagery (monkeys, creamed corn, a little person in a red suit wearing a distressing white mask, oh my), the film foregrounds the core truth of the Twin Peaks story: that Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) was repeatedly raped, and ultimately murdered, by her own father (Ray Wise). Where the show was often amiably goofy with lots of charming small-town characters to cut the darkness a little, here, now, was what it was all about, and there would be no more distractions. Lee’s performance, which looks to have been terribly exhausting, is astounding. She has to play the torture of her life, while hiding it from everyone else. Still, she’s losing her handle on things. In the larger story of Twin Peaks, evil is personified by a supernatural figure named Bob (Frank Silva). Initially, when Laura is being raped, she believes it is Bob doing it. And it is. But it’s also her father, and the moment when Laura realizes this, the way Lynch wrote and filmed it, and the way Lee plays it, is shattering. You can almost feel her mind coming apart in that moment. When Chris Rodley theorizes that the reason the film was met with hostility was that all of the show’s lightness had been drained out of it, leaving only horror behind, Lynch said, “That’s what it was all about—the loneliness, shame, guilt, confusion and devastation of the victim of incest. It also dealt with the torment of the father—the war in him.”

Despite Fire Walk With Me’s disappointment, Lynch’s output continued at a reasonable pace. Though it would be five years until his next film, 1997’s Lost Highway (other than the Twin Peaks movie, this is the film that most unambiguously belongs in the horror genre), he would release three pictures in the nine years following it. The beautifully humane The Straight Story (rated G!) came out in 1999, and just two years later, he released Mulholland Drive. More even than Eraserhead, Mulholland Drive must count now as Lynch’s signature film. A story of murder, sinister, otherworldly cowboys, awakening sexuality (Naomi Watts’s Betty also discovers new desires), dreams, and Hollywood, the film began as a TV show, which was quickly aborted. Lynch transformed it into a two-and-a-half-hour epic of unease and dread. It earned Lynch his third Oscar nomination for Best Director (he was also nominated for The Elephant Man and Blue Velvet) and continues to puzzle and absorb almost 24 years later. It introduced new audiences to Lynch, and is probably the main reason the term “Lynchian” has become not only overused, but misused.

IN HIS LONG ESSAY “David Lynch Keeps His Head,” about the making of Lost Highway, David Foster Wallace described the director as a “heroic auteur,” adding that “Lynch has remained remarkably himself” and has “held fast to his own intensely personal vision” as an artist. He goes on to try and define “Lynchian.” He writes:

An academic definition of Lynchian, might be that the term “refers to a particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.” But like postmodern or pornographic, Lynchian is one of those Potter Stewart-type words that’s definable only ostensively – i.e. we know it when we see it.

This is, of course, the whole point of David Lynch. Few American filmmakers have carved out an aesthetic path as individual, bizarre, and irreproducible by those seeking to imitate than David Lynch. “Lynchian” isn’t simply a matter of being weird. It is, or was, a matter of being David Lynch. Which means that nothing will ever be Lynchian again.