Death, Lies, and Video Files

What online fights about a single deadly missile in Ukraine can teach us about the future of news coverage and conspiracy theories.

ON SEPTEMBER 6, A MISSILE HIT a busy market in Kostyantynivka, a Ukrainian-controlled town not far from Russian-controlled territory. According to Ukraine’s interior ministry, at least seventeen people were killed, including a child, and more than thirty others were injured.

The origins of the missile remain unclear, even two weeks later. This week, the New York Times released a thoroughly reported story (it carries six bylines) presenting evidence that the missile was “a tragic mishap”—that it was launched by Ukrainian air defense forces. But Ukrainian authorities have disputed the Times report, claiming that fragments of the rocket indicate it was Russian in origin.

At times, the intense debate about the missile’s origin has veered into the territory of conspiracy theorizing. I want to focus on a specific part of that fight—an episode that reveals how the digital practices now routinely used by Western news outlets can inadvertently drive controversy, stoke conspiracy theories, and serve the purposes of illiberal propagandists like Vladimir Putin. The story that follows is a cautionary tale for the world we now inhabit.

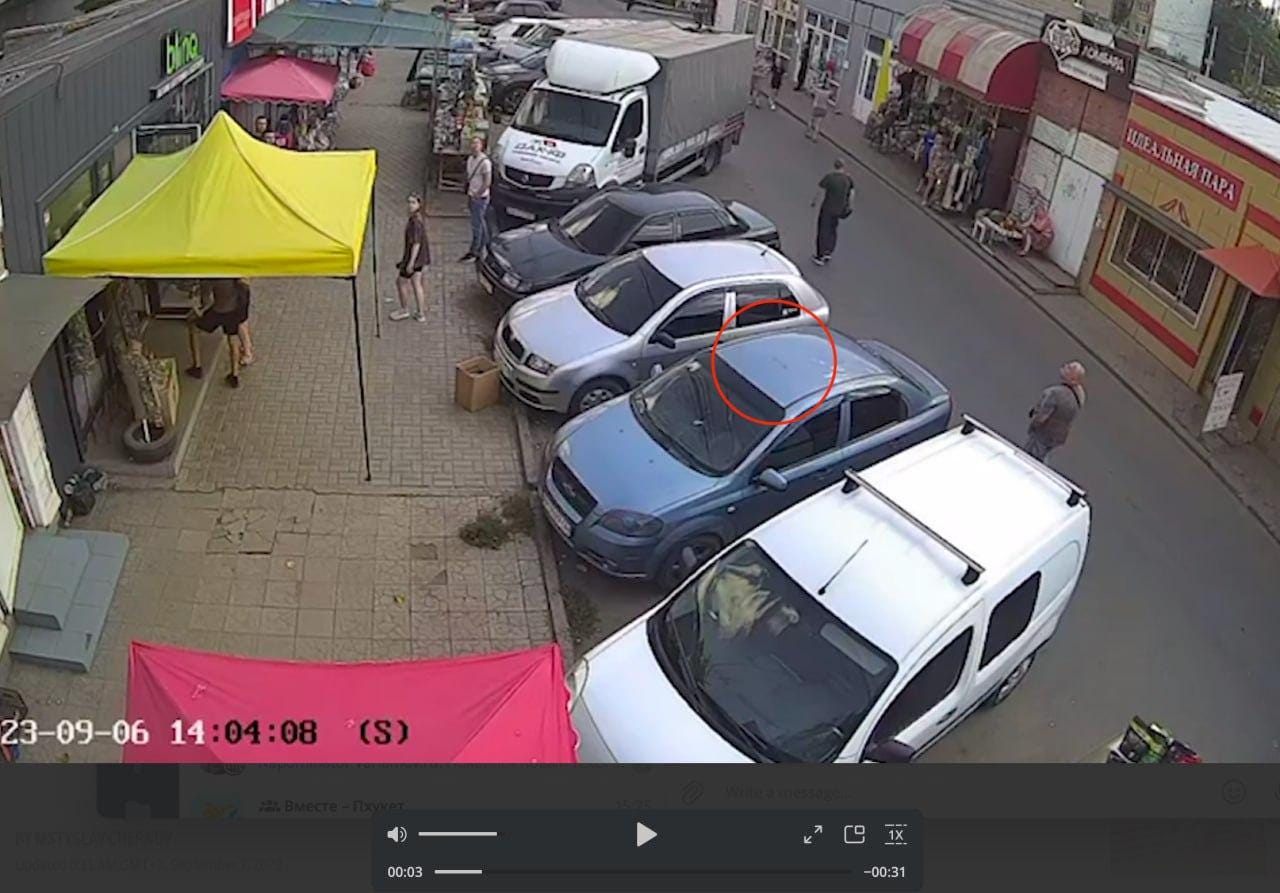

AFTER THE ATTACK, Volodymyr Zelensky’s media team released a video from CCTV footage taken seconds before the missile struck.

You will notice that in the very first second of the video there is a loud bang and then (what you won’t be able to see unless you pause and rewind many times) in the third second, there is a brief flicker of a reflection in the roof of a blue Chevy. If you pause at the exact right moment, you will see that this flicker appears to be a reflection of the missile passing overhead just before it detonates.

Immediately after it was released, this video was scrutinized by people on Russian Telegram, who quickly arrived at a consensus: If you triangulate the position of that street and the trajectory of the rocket, they claimed, you would come to the conclusion that it arrived from the northwest.

As it happens, Russia is east of Donetsk. So the people on Russian Telegram went on to conclude that this missile was actually launched by Ukraine—as a false flag operation meant to frame Russia for the killing of Ukrainian civilians.

The following day the Associated Press released a video montage of the attack. Take a look.

You will notice some changes. The clip featuring the CCTV footage of the street and the rocket blast is now further into the video, buffered by other video sources. The AP has also added their logo as a watermark to the video and equalized the sound (the initial bang of the explosion is clearly less loud).

Along with these editorial changes the AP made one other modification. In the AP version of the video, the rocket reflection is gone from the roof of the Chevy.

Most observers did not notice this change.

You know who did notice it? People on Russian Telegram. Seeing this change, they concluded that, in addition to the attack being a Ukrainian false flag, the Western press was now trying to orchestrate a coverup by disappearing the “evidence.”

So what really happened?

OUR TEAM at Samizdat Online, the anti-censorship platform that my co-founder Michael Sprague and I launched after the war began, reached out to the AP for a comment and explained to them that the missing rocket reflection was making people lose their minds.

At first, the AP was not willing to address the issue on the record. But after several days replied with the following statement:

AP did not alter the video.

Due to multiple technical conversions necessary to acquire, produce, publish and upload the video, low-resolution versions of the video may not have as much fine detail as the high-resolution versions we distribute to our customers globally.

I’ve spent two decades around video encoders, and when I saw the AP footage, I immediately suspected that something had happened like what the AP conceded in its statement: that when the AP’s video editors made their montage, they had to re-encode the CCTV video footage. And what several kinds of video encoders do (in order to make the files as small as possible) is try to change things as little as possible from frame to frame.

They essentially treat regions of the video that are not “moving” (like the parked Chevy) as a still picture. The less that picture changes from frame to frame, the less data is needed to draw it in the next frame.

Which is what the AP finally admitted: They did not alter the video deliberately—but they did compress it in a way that hostile viewers noticed, and seized upon.

This clash shows how ill prepared Western news outlets are for confronting illiberal threats.

We live in a world where Vladimir Putin and the forces of illiberalism flood the zone with lies and multitudes of contradictory versions of the same events in an effort to exhaust the public and have us all throw up our hands.

But Western organizations such as the AP have no tools to guarantee the authenticity and chain-of-custody of the content they distribute. They still don’t understand how a flicker (or lack of flicker) in a compressed video they release online can play directly into the hands of authoritarians, conspiracists, and creators of propaganda.

THIS ISN’T A CRITICISM OF THE AP so much as an observation that Western news media are in a (proverbial) gunfight armed with a badminton racket and a banana.

Realistically, the best that press outlets can do is add endless disclaimers explaining their process: that they’re not intentionally tampering with the media and that conversions sometimes introduce misleading artifacts, and maybe provide links to the originals. But I am dubious that such steps will be particularly effective in putting at ease the minds of the kind of people who have nothing better to do than scrutinize videos one frame at a time in search of conspiracies. Especially since some of those who do so are paid by Putin to do exactly that.

The ideal solution: a world in which all media (not just videos but still pictures, audio recordings, PDFs, etc.) is fingerprinted, and then any version derived from the original is cataloged as version X.y, and the full history of alteration is available for public scrutiny and kept on some publicly accessible blockchain so that any modification can be tracked to a specific moment in time. There are several projects circling around this concept, and the sooner they’re adopted by organizations like the AP, the sooner normal people trying to stay informed can return to a world where the media they consume is trustworthy.