Dissident’s Arrest Puts Putin’s Past on Trial

From the KGB in the 1970s to war autocracy today, repressions come full circle.

WHILE POLITICAL ARRESTS and prosecutions have become the norm in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, particularly since the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, last week’s arrest in St. Petersburg of 66-year-old writer, former history teacher, and veteran dissident Alexander Skobov stands out. One reason is Skobov’s uncompromising, defiant attitude. According to the independent Russian site Mediazona, which monitors the cases of political prisoners, Skobov not only shouted “Glory to Ukraine!” and “Death to the murderer Putin!” at his arraignment, but refused to rise when the judge entered the courtroom, declaring that he saw “no point in participating in this farce” other than “spitting in the court’s face.”

Skobov is also one of a handful of Putin-era dissidents whose history of rebellion stretches back to Soviet times. A member of an anti-Soviet left-wing group that espoused what it members believed to be true and humane communism, he was first arrested in 1978, spent a total of six years in a psychiatric prison (one way the Brezhnev-era Soviet Union tried to hide its barbarity), and had the distinction of being a co-defendant in the last case brought under Article 70 of the Soviet penal code, “anti-Soviet agitation.” (The case was closed when the article was repealed in 1989.)

But, even more remarkably, Skobov’s political persecution implicates a little-known and deliberately obscured part of the KGB career of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin: His involvement in the persecution of dissidents as part of the KGB’s Fifth Chief Directorate, created in the 1960s to combat political dissent and other ideological threats.1

ACCORDING TO PUTIN’S OFFICIAL BIOGRAPHY, his career in the KGB was spent serving in foreign intelligence and had nothing to do with domestic repressions. It is true that from 1985 to 1990 he was stationed in Dresden; both Putin himself and his former colleagues from the KGB (and its East German analogue, the Stasi) have insisted it was a boring, banal, paper-shuffling job, though some argue that the truth was far less mundane and perhaps more sinister. (Possibilities range from helping smuggle Western technology into Warsaw Pact countries to coordinating East German aid to the West German Red Army terror group.)

When the great Russian writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a towering dissident figure in the Soviet era, was asked in 2007 why he felt comfortable meeting with Putin and even accepting a state prize from him given Putin’s KGB career, his answer invoked Putin’s alleged distance from political persecutions. “Yes, he was an officer of the intelligence services, but he was not a KGB investigator,” Solzhenitsyn told Der Spiegel, adding that “service in foreign intelligence . . . is not a negative in any country” and invoking George H.W. Bush’s onetime position as head of the CIA.

Moral equivalency aside, it turns out that the official version Solzhenitsyn accepted as fact was, in all likelihood, merely a cover story.

The July 2022 biography Putin by British journalist Philip Short, praised by reviewers as “magisterial” and uniquely comprehensive, reveals that Putin’s first KGB job, from July 1976 to late summer of 1979, was in the Leningrad branch of the dissent-policing Fifth Directorate. According to Short, “The recollections of his friends and KGB colleagues, as well as his own statements, leave no doubt that he did” work in that department. So do the recollections of some dissidents: Andrei Reznikov, who co-edited the samizdat magazine Perspektivy (“Perspectives”) with Skobov, which led to Skobov’s 1978 arrest, asserted in 2012 that he was virtually certain Putin oversaw his own arrest at a KGB-thwarted protest the same year. Putin discussed the suppression of that protest in some detail in a 2000 conversation published in a collection of interviews—but claimed that he had nothing to do with it and simply heard it discussed around the KGB cafeteria.

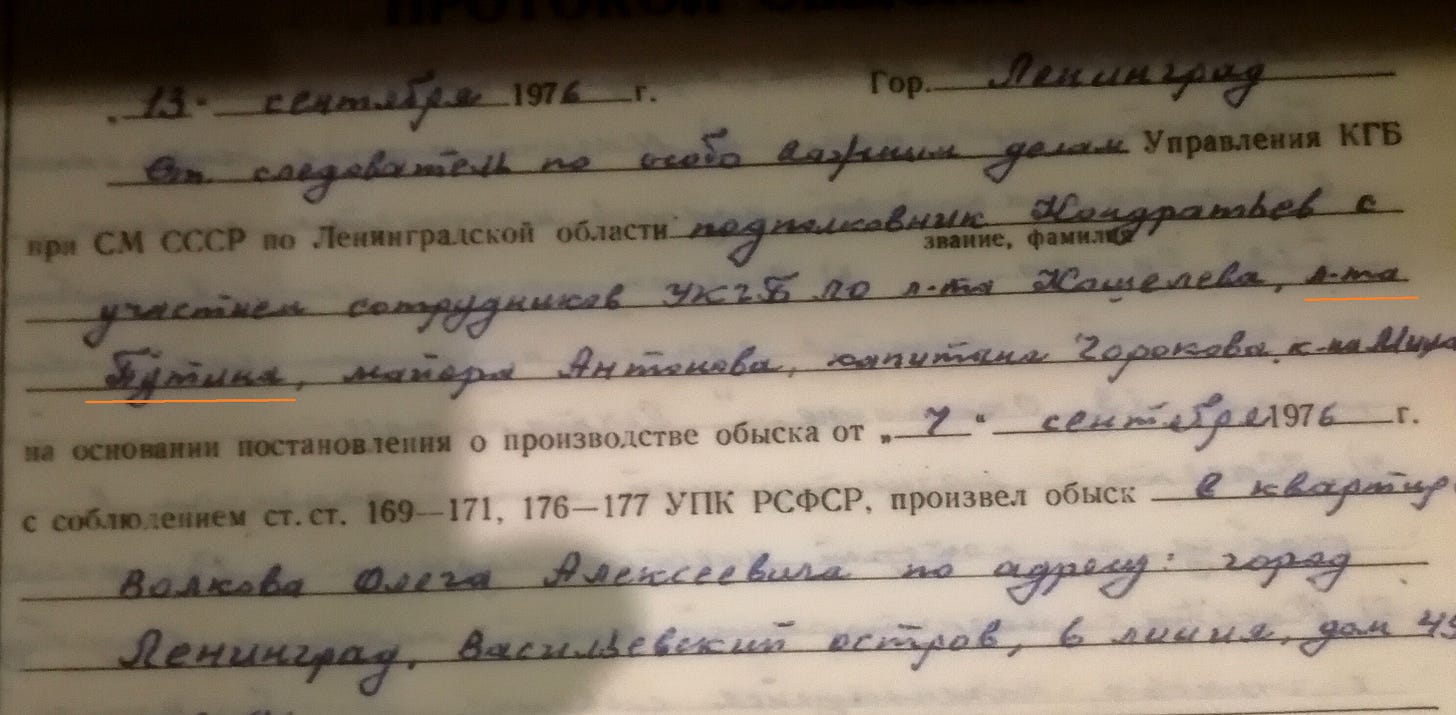

None of that, however, amounted to documentary evidence—until two years ago, when a historian uncovered an official report dated September 13, 1976, listing “Lt. Putin” as one of five KGB operatives who searched the Leningrad apartment of dissident artist Oleg Volkov. Volkov and his friend Yuli Rybakov had decorated a wall of the Peter and Paul Fortress—an infamous tsarist-era political prison—with huge graffiti that said, “You crucify freedom, but the human soul knows no shackles.” After the fall of the Soviet Union, Rybakov—at one point a deputy in the State Duma—was able to retrieve his old case files, which he donated to the Political History Museum in St. Petersburg. He never bothered, however, to look closely at the details of many papers in the huge trove of documents, and told the independent news site Meduza in late 2022 that he was genuinely shocked when a historian named Konstantin Sholmov found Putin’s name in the report.

As it happens in the small world of St. Petersburg dissident politics, Rybakov is the friend at whose apartment Skobov was arrested on April 2.

Alexei Cherkasov, a board member of Memorial, the now-banned human rights group whose principal task is to keep records of political terror and repression in Russia, told the independent news site Agentstvo (“Agency”) that given his job in the Fifth Directorate, Putin was almost certainly involved, at least tangentially, in Skobov’s 1978 case. But even if he wasn’t, there is at most one degree of separation between Skobov’s Soviet-era career as a dissident and Putin’s Soviet-era career in the KGB.

IN POST-SOVIET RUSSIA, Skobov soon found himself a dissident again. He strongly opposed Boris Yeltsin’s war in Chechnya in 1994-1996. As an activist and a columnist for the independent website Grani (“Frontiers”), he was an uncompromising opponent of the Putin regime, vehemently criticizing Russian liberals for their accommodationist stance. In 2014, he fully embraced Ukraine’s “Revolution of Dignity” and accused the Putin regime of embarking on an “unabashedly Hitlerian foreign policy” with the annexation of Crimea and the undeclared invasion of Eastern Ukraine. His insights from that time now seem remarkably prescient: he wrote about Putinism as a rejection of limitations on the power of the state, whether domestically or externally; about Putin’s war as a war against the rules-based international order and for a return to “the forcible redrawing of borders” and “imperial spheres of influence”; about “ruscism,” or Russian fascism, as “the ideology of the perpetually aggrieved.” Eight years before Bucha, Skobov asserted that the Russia-Ukraine conflict was fundamentally about “the world of barbarism versus the world of civilization.”

At the time, one could write such things in Russia and still lead a legal if marginal existence. Grani was banned and blocked in Russia but was still available to Russian readers through mirror sites, and Skobov wrote for it without repercussions.

As the low-level warfare in Eastern Ukraine turned to a full-fledged war, Skobov’s position became increasingly precarious, yet he remained undaunted. In his social media posts and interviews, he urged Russians to support the Ukrainian armed forces, cheered the Ukrainian strikes on the Kerch Bridge connecting Crimea to the Russian mainland, and endorsed the armed struggle of Ukraine-backed Russian rebels who carried out raids on Belgorod and other Russian border regions. His arrest was only a matter of time—and now, his friends fear that his death may be only a matter of time as well, given his severe medical issues including diabetes and asthma. Despite these problems, and despite the fact that Skobov is the principal caregiver for his 90-year-old mother, the court has remanded him to pretrial detention until June 1.

Discussing Skobov’s arrest and recalling KGB lieutenant Putin’s surprising connection to his friends’ persecution—and very possibly Skobov’s own persecution—in the 1970s, exiled Russian journalist and satirist Viktor Shenderovich saw the grim symbolism:

Back then, this little lieutenant was small KGB trash. Now, he’s big KGB trash occupying the post of president of the Russian Federation. The state is different, the trash is bigger—but it’s the same man, and he has Skobov arrested at Rybakov’s apartment. Half a century later, the circle has closed.

The dissidents of Skobov’s generation, who battled the Soviet regime against seemingly impossible odds in the 1970s and 1980s, lived to celebrate a victory when the regime collapsed in 1991. We can still hope that today’s dissidents will someday celebrate the defeat of the Putin regime, in the war in Ukraine and ultimately at home as well—and that Skobov, once again defying the odds, will live to see that day.

In 1989, the directorates of the KGB were renamed, with the Fifth Main Directorate becoming the Directorate for Protection of the Union and the Constitutional Order, or for short, Upravlenie “Z”—Directorate “Z,” a slightly eerie coincidence with the official code name of the “Special Military Operation” that has come to define the Putin presidency.