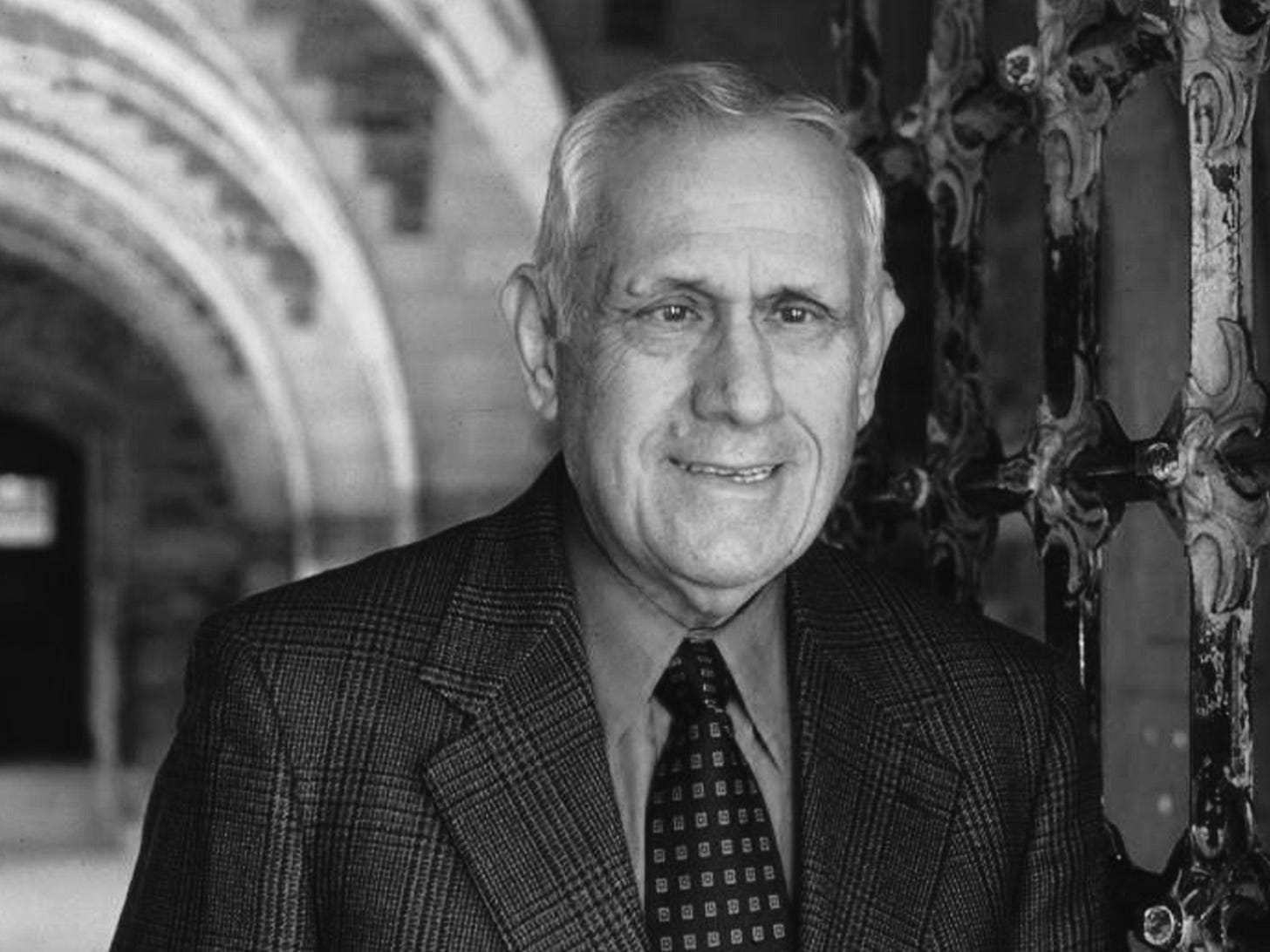

Don Kagan: The Man, the Legend

Remembering Donald Kagan, 1932 - 2021.

As I look at my library right now, no single author occupies a larger space on my shelves than Donald Kagan. I met Professor Kagan only once, and that was the closest I ever felt to meeting God. He agreed to privately read Thucydides with me, which I guess would be like having God invite you to join his Bible study group. Alas, a pandemic happened, and it never came to pass.

Yet despite the fact that I never studied with Professor Kagan face to face, he influenced my education in foreign affairs more than anyone else. Through his own writings. Through the work of his son, the great Robert Kagan, and through his superstar doctoral student, Eric Edelman, who has taught me everything I know.

So when I heard the news of Kagan’s passing at the age of 89, I didn’t mourn. Instead, I was grateful to have been able to touch some small part of his amazing legacy, one of educating generations of foreign policy thinkers and practitioners.

The philosopher who has contributed the most to thinking about international relations is Thucydides, and the most important student and teacher of Thucydides was Donald Kagan.

The Cold War was at its peak when Professor Kagan made his name in academia and policy circles. Confronted with a great power conflict for the first time in their history, the Americans turned to Thucydides. And so did Kagan.

The Peloponnesian War resembled the Cold War in an important way: It was the story of a bipolar order that had led to war. The conventional wisdom looked at this analog and decided that the sophisticated and democratic Athenians were Americans, while the oligarchic savages of Sparta were the Soviets.

But Professor Kagan broke that consensus view. True, the domestic way of life of the Americans looked more like Athens, Kagan argued, but NATO was much closer to the Spartan League. This was a relatively small observation—he would offer much larger contributions. But it was indicative of how Kagan was always looking for what everybody else had missed.

Those who studied Thucydides tended to view him as a philosopher god among men. For Kagan, Thucydides was a great man—an extraordinary man—but a man, nonetheless. He was an Athenian general living in exile in Sparta who had his own agenda and was not a mere spectator of the war. This sober appreciation of Thucydides and human nature writ large made Professor Kagan the best reader of Thucydides’s history—and also one of the best observers of politics.

Kagan’s reading of the Peloponnesian War would produce several books, including his exhaustive, four-volume interpretation of Thucydides’s history. Through his writings, he used the great Greek war to study politics and human nature.

His volume on Pericles studied statesmanship. He appreciated that individuals could bring a nation to its glory or its knees. Two years ago, at a dinner, surrounded by adoring students bidding for his attention—a bid I proudly won!—somebody asked him what single advice he would give the president if he were to be summoned to the Oval Office. Not missing a beat, Kagan shouted, “resign!”

(I never asked him if he saw Cleon in Donald Trump, though I wish I had. Even though Cleon, the stupid demagogue, died, he opened the door for the later arrival of the clever Alcibiades who would bring the end of democracy in Athens.)

Kagan’s first extraordinary observation as a historian was a common sense understanding of politics that historians too often overlook. Still a doctoral student, he broke the duopolistic understanding of Corinthian politics, which held that Corinth was a city divided between democrats and oligarchs. Kagan found a third, and most important, faction: The centrists with moderate characteristics of both factions who were constantly being courted by the two extremes. They were the middle faction of politics, influential in their times, but neglected by historians—one cannot help but wonder, when future historians write the history of our time of The Squad and Trumpism, whether there will be a Donald Kagan to note the influence of the Mitt Romneys and Joe Manchins.

But Kagan’s foundational insight was that you could study human nature through war.

Political scientists have long pontificated about the origins of war. The “steps to war theory,” “the rationalist explanation for war,” the “realist” model, the “bargaining model,” and so on. Professor Kagan had a much simpler view: War is violence, and violence is a part of the human condition. As long as an adversary is convinced that it can achieve its objectives via violence, it will do so. The first war in the human story is Cain’s murder of Abel, making war as old as humanity itself. The possibility of war originates from humanity, Kagan taught, and so it will endure as long the human race endures.

That’s not a happy view, but we’ve seen nothing to suggest it is incorrect.

With the end of the end of history, protecting our way of life in the liberal world begins with an appreciation of the human condition, virtuous statesmanship, and the relationship between humans and the states they are subordinated to.

Kagan had—and still has—a lot to teach us about all of these.