Donald Westlake, Criminal Mastermind

The master of the crime novel has more to offer than just his “Parker” stories.

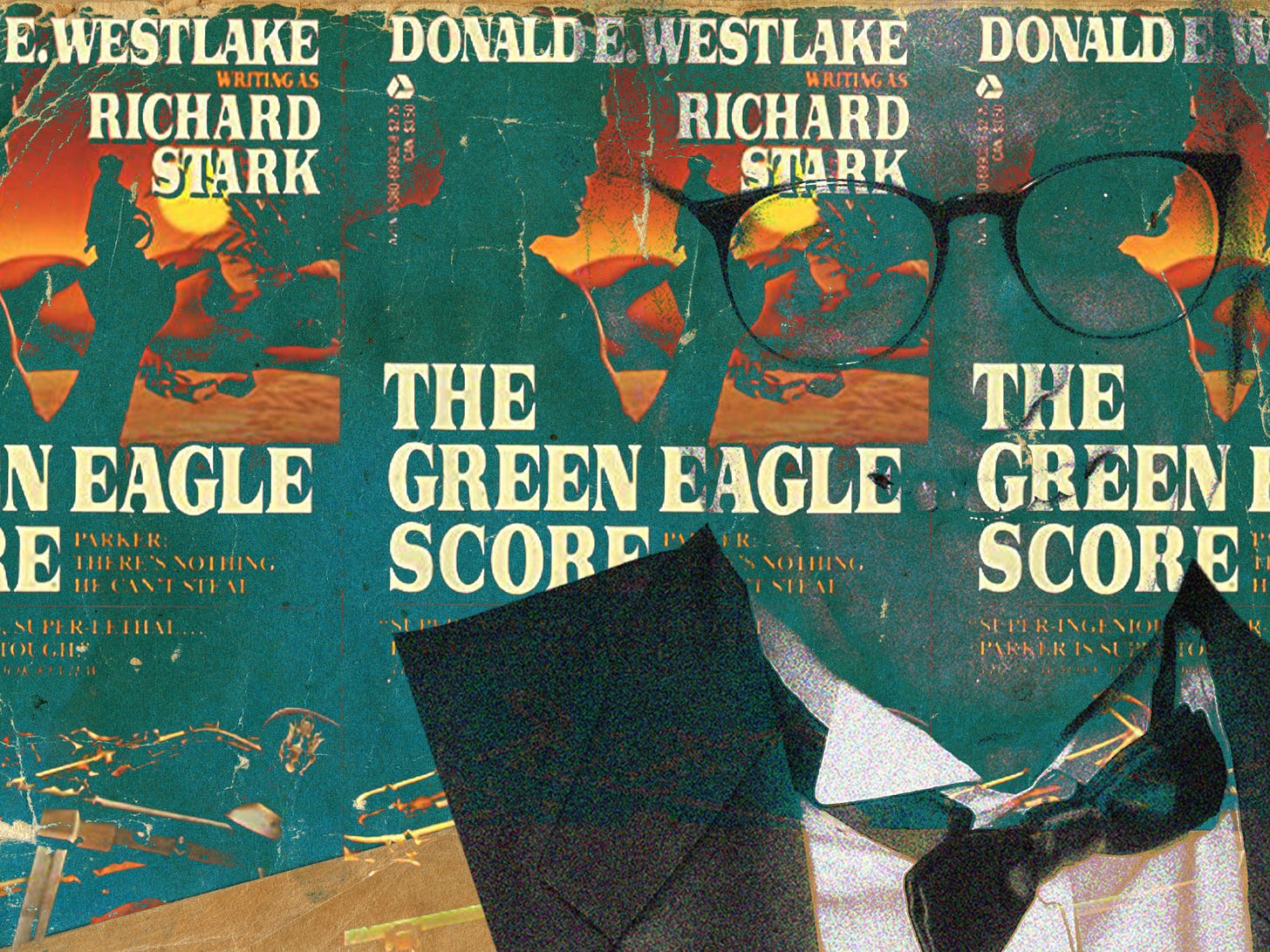

Donald E. Westlake, writing under the pseudonym Richard Stark, begins his novel The Green Eagle Score this way:

Parker looked in at the beach and there was a guy in a black suit standing there, surrounded by all the bodies in bathing-suits. He was standing near Parker’s gear, not facing anywhere in particular, and he looked like a rip in the picture. The hotel loomed up behind him, white and windowed, the Puerto Rican sun beat down, the sea foamed white on the beach, and he stood there like a homesick mortician.

“Parker looked in at the beach” tells the reader that Parker is standing in the sea without ever actually saying as much, and that “like a rip in the picture” simile is about as perfect a way to indicate this vacation is about to end as I can imagine. The way those six words sit amidst the rest of the paragraph means that they function almost exactly as the image does in the narrative: virtually every other word is, or is associated with, beaches and blue skies, and then there’s this rip in the picture.

The Green Eagle Score was Westlake’s tenth novel about Parker, the possibly (probably) sociopathic thief who tends to kill time while waiting to meet someone to talk about pulling a job by doing things like watching TV with the sound off. In the first Parker novel, The Hunter (twice adapted into films, first as Point Blank (1967), starring Lee Marvin, and again as Payback (1999), starring Mel Gibson), he accidentally kills a completely innocent civilian in the course of carrying out his plan, and what upsets him about this horrible turn of events isn’t the loss of life, but rather the potential trouble a dead body might cause him. In The Sour Lemon Score, Parker eats a cookie and notes that “it had a good taste to it.” Coming as it does from Parker, that compliment suggests to me that this was one damn good cookie.

There are twenty-four Parker novels in all. The first sixteen were written between 1962 and 1974 (four came out in 1963 alone) and the final eight—following a 23-year hiatus from the character of Parker—were published between 1997 and 2008, the year Westlake died. The twenty-four Parker books are Westlake’s most famous, beloved, and respected novels, not only that he wrote but in the entire history of the crime genre. But he was prolific in other genres as well, his body of work (between novels, short story collections, and non-fiction) totaling well over one hundred volumes.

Westlake’s other famous series character is John Dortmunder, who features in fourteen novels and a collection of stories. The Dortmunder novels are perhaps best described as “capers”—like Parker, Dortmunder is a thief, but while the Parker books are as dark and hardboiled as they come, Dortmunder’s misadventures are decidedly lighter, funnier. Yet Dortmunder wouldn’t exist without Parker. Westlake intended Parker to be the protagonist of The Hot Rock, the first Dortmunder book, but he realized the plot was so absurd that it had to be a comedy. This not being suitable for someone like Parker, Dortmunder was invented. (In a pretty hilarious bit of meta playfulness, the third Dortmunder novel, Jimmy the Kid, features a kidnapping scheme devised by one of Dortmunder’s cohorts that is lifted, by the character, from a fictional Parker novel called Child Heist, excerpts of which appear in Jimmy the Kid.)

When it comes to writers, especially crime writers, who are best-known for their series characters, I often lament the fact that their standalone novels are inevitably and unfairly overshadowed. For example, of the ten or so novels I’ve read by John D. MacDonald, my favorites are not part of his series of Travis McGee mysteries. It’s less cut-and-dried with Westlake, as the Parker books, especially the original sixteen, are unassailable, but I was first thunderstruck by a few of his standalones. Of the comic novels by Westlake I’ve read, my favorite is A Likely Story, a fairly inside-baseball satire of the publishing industry. The main character is an editor working to compile an anthology of new and classic Christmas stories for the holiday season, and it contains many jibes at famous writers; among others, there’s an affectionate one aimed at Stephen King, and a more acerbic one at the expense of Jerzy Kosinski. But it was two extremely dark novels written in the late ’90s/early ’00s that first made me a Westlake acolyte.

First was The Ax (1997). Essentially a dark satire without jokes, The Ax is about Burke Devore, a man who has been laid off from his manager position at a paper mill. Driven to despair after a year of unemployment, Devore eventually develops a complicated plan that culminates with him murdering other men like him, his competitors for management positions in the paper industry. Paper being a specialized business, he narrows these competitors down to six men, who, over the course of the novel, he will hunt down and murder. A disturbing and furious novel, The Ax never lets the reader off easy. If you find yourself naturally sympathizing with Devore, you will then need to deal with the fact that none of his victims are guilty of anything. Devore reflects:

I knew who the enemy was. But what good does that do me? If I were to kill a thousand stockholders and get away with it clean, what would I gain? What’s in it for me? If I were to kill seven chief executives, each of whom had ordered the firing of at least two thousand good workers in healthy industries, what would I get out of it?

Nothing. His problem, he goes on to say, are “[t]hese six résumés.” And Devore never develops a taste for killing. He becomes very cold about it, but his hatred for what he’s doing is always there, clearly read between the lines even when it’s not explicitly stated. But he keeps killing.

Better still, for my money, is The Hook (2000). The Ax and The Hook seem unavoidably connected, not just by their similar titles, but also by their central ideas of desperate people doing terrible things because the world around them regards them and their fortunes with complete, icy indifference. Basically Westlake’s riff on Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train, The Hook is about two writers: one, Bryce Proctorr, is quite successful but currently blocked. The other, Wayne Prentice, writes plenty but can’t sell any of it. The two men meet one day, get to talking, and share their various difficulties. Proctorr makes an offer: if Wayne gives him one of Wayne’s unpublished manuscripts, Proctorr will get it published under his name, and the two will split the proceeds. There is, however, one other thing. In order to earn his keep, Wayne will have to murder Lucie Proctorr, Bryce’s estranged wife, who is making their divorce difficult. Wayne, after discussing the matter with his own wife, agrees.

Wayne goes through with the murder, and that section is one of the most disturbing I’ve ever read in crime fiction. He doesn’t shoot her, or stab her, but rather tries to beat and strangle her to death, something he finds very difficult to do. Physically difficult, not psychologically: “He couldn’t do it, whatever he was trying to do he wasn’t doing it, break her neck or twist off her head or whatever it was, it wasn’t working…” And then later: “Until this instant, there had been nothing sexual in it. . . . Now, the smell of her, the warmth of the body under his, that faint sound of her breath in and out of her broken nose, and he became aware of her as a sexual being.” And finally “Her bowels had released. No fear any more of being turned on.”

Despite telling his wife later that murdering Lucie was “worse than you can know,” the murder itself, and his subsequent behavior, makes it clear that Wayne is not all that bothered by what he has done. When I read The Hookover 20 years ago, this aspect of the novel was a disquieting revelation, not just about the character, but about people who commit murder in the real world. Because of course it must be true that many murders that are not the result of some kind of passionate heat of the moment or form of insanity are committed by people who have lived their whole lives believing they were incapable of such horror until they actually found themselves doing it. And, they realized, it wasn’t such a big deal to them, personally. This is not something that will haunt them, but if you’d asked them a week ago they’d assure you they would never get over committing such an evil act.

For this and other reasons, The Hook has been lodged in my mind since 2000, an unshakable reading experience. Like Charles Willeford, whom he admired, Westlake was a master at depicting complete moral bankruptcy without ever signaling what he was doing. He was not interested in holding the reader’s hand and assuring them that the bad things they are reading about are, indeed, bad. Lately there has been a demand, at least from certain segments of social media, for artists to make it clear where they stand morally in relation to the behavior of their villainous characters. Westlake was too great an artist for that kind of nonsense. Parker is completely amoral, he cares only about himself (and, after eight novels, Claire, his companion for the rest of the series, but I’m convinced Westlake only created her because he got tired of writing the same things about how Parker spent his time between jobs; anyway, her connection to Parker shows her to be morally compromised herself). The limited sense of honor he does have—if you don’t betray me, I won’t betray you—is only practical. It’s not born of a sense of right and wrong, but rather of a desire to not cause himself unnecessary problems.

As I said before, Westlake wrote in a variety of styles and genres. When he was starting out, he briefly wrote science fiction (the story collection Tomorrow’s Crimes collects all of his SF work, including his short novel Anarchos) before he became disillusioned with the genre’s focus, at that time, on cold technological matters, and a later novel, Humans(1992), is a strange, and very good, half-light half-dark apocalyptic fantasy. But crime, and the moral questions inherent in it, was his home, his country, and there’s never been anyone better at exploring it.