Don’t Bury Ukraine

The war effort is doing better than detractors claim—but aid is still needed, and the doomsaying may become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

THIS MONTH HAS SEEN A TANGIBLE VIBE SHIFT on the war in Ukraine. Between Republicans in the House and Senate blocking a $110 billion package that includes military aid to Ukraine as well as Israel and Taiwan by tying it to border-security measures, dire warnings that U.S. aid may have to stop without new funding by the end of the year, and media reports detailing the purported failure of the Ukrainian counteroffensive this fall, the narrative that the wheels are falling off the U.S.-backed Ukrainian war effort is spreading.

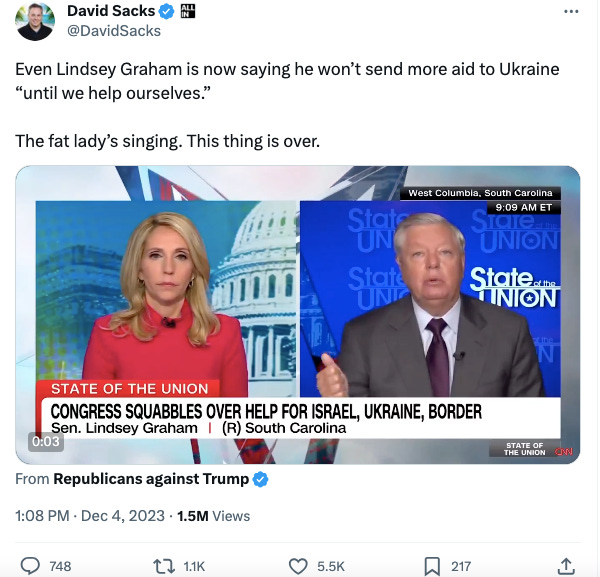

And, predictably, it is being met with downright glee in some quarters. Tech venture capitalist and foreign policy dilettante David Sacks, a loud voice in the anti-Ukraine chorus from day one, is crowing:

Ditto for “anti-establishment” muckraker Matt Taibbi, a longtime hater of all pro-Western forces in former Soviet space:

On Sunday, one of the leaders in the anti-Ukraine bloc in Congress, Sen. J.D. Vance of Ohio, told CNN’s Jake Tapper that nobody had ever seriously believed that “Ukraine was going to throw Russia back to the 1991 borders” and that it was imperative to have negotiations in which “Ukraine is going to have to cede some territory to the Russians” and bring the war to a close. Vance also shed some crocodile tears over the “great human tragedy” of “hundreds of thousands of Eastern Europeans, innocent . . . killed in this conflict.”

But how accurate is this assessment of the current situation? And are “land for peace” negotiations an inevitable, feasible, or desirable outcome?

TO SOME EXTENT, THE “UKRAINIAN FAILURE” NARRATIVE reflects the short-term thinking that has generally plagued Western responses to the war. (As some have said, we keep thinking of it as a television show in which storylines get satisfyingly wrapped up on schedule—but this is the real world.) It is true that the clock is ticking on a Ukraine deal, with Congress scheduled to recess at the end of this week—but last-minute dealmaking between Congress and the White House has been the standard this whole year. And even if a deal doesn’t come together this week, there are other possibilities. A deal could still be put together early next year. The White House may still use the Lend-Lease authority to loan weapons to Ukraine which it received from Congress in 2022 and which it has kept as a backup option, evidently because the continuing flow of assistance to Ukraine seemed assured thanks to bipartisan support. And there are moves to transfer to Ukraine frozen and confiscated Russian assets in the United States; so far, these initiatives have focused on directing such funds to the civilian needs of Ukraine’s reconstruction, but House Speaker Mike Johnson has suggested using them for military purposes and claimed that there was “great enthusiasm on the Republican side” for this idea. (Globally, frozen Russian assets total about $300 billion.)

The notion of Ukraine’s collapsing war effort needs to be taken with a grain of salt as well. To some extent, as pro-Ukraine analysts such as Russian-American journalist and video blogger Michael Nacke have argued, the perception of failure is due to “overly optimistic” expectations—partly because of Ukraine itself overselling its counteroffensive, with some officials even claiming that Crimea would be taken by fall, and partly because of the impressive success of the previous Ukrainian counteroffensive in the fall of 2022, which resulted in the recapture of Kherson and the panicked flight of Russian troops from Kharkov. In 2023, not only did Ukraine fail to retake the major coastal city of Melitopol, one of the goals set for the counteroffensive, its troops did not even make it to Tokmak, 32 miles north of Melitopol.

Nonetheless, Nacke (who has at times angered others in the pro-Ukraine camp by challenging its narratives) insists that while the Ukrainian counteroffensive certainly cannot be regarded as a success, it also cannot be seen as a fiasco like the Russian assault on Vuhledar in January and February of this year, which was thwarted with massive losses in both hardware and human lives. In his view, the counteroffensive did not leave Ukraine in a worse position than before: the Armed Forces of Ukraine did take some territory and kept its losses fairly low. He also strongly disputes the idea that Russia is doing well on the frontlines, despite its claims to have seized the initiative. Nacke sees evidence of Russian floundering in generally unsuccessful, high-risk attempts to advance in various locations despite extremely unfavorable weather, and notes that even Russian voyenkory—“war correspondents,” or milbloggers—sometimes break out of the agitprop mold to acknowledge that things are not going well at all.

In the latest news, the Ukrainians are pushing back at Avdiivka, where the Russians had previously made extremely modest gains, and not only holding on to their beachhead near the village of Krynky on the Russian-occupied left bank of the Dnipro river but stepping up their assaults and inflicting significant losses on Russian troops trying to recapture those positions. According to Prague Municipal University professor Yuri Fedorov, a Russian émigré military expert, one popular theory has been that Russian commanders were under extreme pressure to take something by Vladimir Putin’s announced year-end press conference by December 14; since that deadline is about to pass, Fedorov speculates that the next target will be a victory by March 14, the day of Russia’s planned presidential election.

One way to keep the bigger picture in mind, suggests Nacke, is to consider that when Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, there was a widespread expectation that Ukraine would fall in a matter of days, and Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky was being offered evacuation from Kyiv. As he puts it:

If back then on February 25 or 26 [2022] I had said, “You know, in November 2023, there will be a situation on the frontlines in which Russia and Ukraine have military parity and many people will be saying that this is unfortunate because they had expected a faster Ukrainian victory,” then I, coming back from the future . . . would be told, “Are you mentally ill? Are you losing it?”

And that’s a compelling point—especially if Nacke’s hypothetical time traveler had also reported that Ukraine had managed, among other things, to neutralize Russia’s Black Sea Fleet along its coastline, to make repeated strikes at the Crimea, to improve the protection of its infrastructure from Russian strikes, and to reduce if not completely thwart Russia’s disruption of Ukrainian grain exports.

STILL, WHY THE UKRAINIAN WAR EFFORT hasn’t done better than it has is a valid question. The failure of the counteroffensive is examined in a two-parter in the Washington Post, which looks at, among other things, disagreements between Ukrainian commanders and their British and American allies. Perspectives differ (as always, victory has many parents but defeat is an orphan, and apparently so is a stalemate), but one conclusion that emerges is that Ukraine needed more aid: Part of the contention between the Ukrainians and their Western partners was that Ukrainians felt they were being asked to conduct a Western-style offensive without the powerful air support that allows such offensives to succeed. Aviation is one area in which Russia retains clear superiority, and fighter jets have been slow in coming. More generally, both Western foot-dragging on the delivery of weapons that were seen as too much of a provocation toward Russia—from tanks to long-range missiles—and Western logistical problems such as shortages of ammunition have almost certainly contributed to the stalemate. Some seemingly promising projects, such as a new German contract to supply ammunition to Ukraine or a joint U.S.-Ukrainian venture to produce artillery shells, will not actually deliver until 2025. And while Ukraine has achieved some impressive results in its own war production, particularly with drones, Western aid remains essential.

The aid must continue even if, for the time being, its only effect will be to extend the stalemate. Of course it’s a cruel prospect. But the alternative—an acceptable peace agreement—is as much of a fantasy as Zelensky and Joe Biden drinking champagne together in liberated Crimea this coming New Year’s Eve. For one thing, Russia continues to make it clear that it is not interested in concessions: The latest statements by Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova still include not only the insistence that all the Ukrainian territories Russia has claimed to annex (including ones currently held by Ukraine) must be transferred to Russia, but demands for Ukraine’s complete disarmament and regime change, i.e. “denazification.” In other words, it’s a demand for capitulation and a complete nonstarter as far as negotiations go.

The recent drop in overall pledges of assistance to Ukraine—despite the approval of new packages from Germany and Japan, among others—is not the result of a natural loss of interest in Ukraine’s plight on the part of liberal democracies; it’s the result of deliberate sabotage by antiliberal forces, be it the Trumpified Republican party in the United States or the increasingly Putinized Hungary of Viktor Orbán in the European Union. (Right now, those forces are seemingly attempting to coordinate their efforts, with Hungarian officials reportedly lobbying against Ukraine in closed-door meetings with Republicans at the Heritage Foundation.)

The crowing among the anti-Ukraine set is, at least so far, premature. Much of it is based on shaky facts. (Taibbi, for example, recycles Tucker Carlson’s unsupported—and contradicted—claim that in a classified House briefing last week, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin told members that if they don’t appropriate more money for Ukraine, “we’ll send your uncles, cousins and sons to fight Russia.”) Zelensky’s visit to Washington, D.C. this week, which will include meetings not only with President Biden but with Speaker Johnson and other congressional Republicans, may yet yield results.

But the possibility that Ukraine may get thrown under the bus is real. Morality aside, such a betrayal will be not only tragic for Ukraine but self-defeating for the West. David Sacks, the perennial Ukraine naysayer, recently invoked a short video clip by Zelensky adviser-turned-rival Oleksiy Arestovych as evidence that Ukraine made the wrong choice in siding with “globalists” over “realists.” But whatever one thinks of the mercurial Arestovych, his point in that out-of-context clip was that the “globalists” seemed to be backing away from effective support for Ukraine. And in his latest interview, Arestovych not only rips into America’s far-right GOP donors who are prepared to sacrifice Ukraine to their goal of defeating a Democratic party they literally see as serving “Satan”; he also predicts that if the West does allow Russia a victory in Ukraine, it will make it very likely that Western democracies lose in their confrontation with authoritarian forces in the East and the “global South.” If that’s what Ukraine’s most prominent Zelensky critic is telling us, the politicians meeting with Zelensky in Washington should be listening.