The Echoes of 1800 in the 2024 Election

This year’s momentous vote strangely resembles one of the most consequential elections in American history.

ON THE EVE OF THE 2024 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION, so much of this moment feels unprecedented. Yet historians and political commentators can’t help looking for points of comparison in previous presidential elections—not just the last few cycles, but further back to, say, 1964 (the last time polls were so tight in the runup to the vote) or 1892 (the only other time a defeated former president hoping for a comeback won his party’s nomination).

But I’m struck by the similarities between 2024 and a much earlier election, one of the most consequential in our nation’s history, from the time of the founders: the election of 1800.

During that election cycle, voters debated the value of deporting residents, state legislatures schemed to control their states’ electoral votes, foreign nations attempted to interfere with the outcome of the election, weak parties failed to contain intense partisanship, and the threat of political violence hovered over the election.

Republican candidate Donald Trump made these parallels explicit in his Madison Square Garden rally on October 27, when he pledged to use the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 to deport undocumented citizens. In the summer of 1798, to prepare for a potential war with France, Congress passed a series of bills, including the creation of the naval department, the formation a provisional army, and expansion of coastal defenses. Democratic-Republicans and Federalists joined forces to pass the Alien Enemies Act—one of the laws that would become infamous lumped together as the “Alien and Sedition Acts”—which would go into effect with a congressional declaration of war. The bill empowered the president to deport foreign nationals of the United States’ enemy, but also provided due process protections for residents.

In 1798, no residents were deported under this law, though some French nationals left voluntarily. During World War II, an updated version of this law was one of the justifications for Japanese internment. The Supreme Court repudiated this use of the law for internment in 2018.

Another echo of the 1800 cycle can be heard in the speculation about what state legislatures might do after the 2024 vote. Article II, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution grants each state the right to determine how to apportion its Electoral College votes. In 1800, both Democratic-Republicans and Federalists engaged in a series of machinations to control the vote in key states. Both parties waged intensive campaigns for the New York state legislative elections, knowing the state would likely be decisive in the upcoming election and the legislature would allocate the electors. In Maryland, Federalists explicitly campaigned on changing the methodology for elector selection. The state had long elected its electors directly. Federalists pledged that if they won control of the legislature, they would grant themselves the power to determine the electors. Outraged at this threat on their direct elections, Maryland voters delivered an overwhelming defeat to Federalists, thereby preserving their right to elect the electors themselves.

The disturbing parallel to 2024: the possibility that Republican-controlled state legislatures in a handful of states—such as Arizona, Georgia, North Carolina, Wisconsin—might do what they refused to do in 2020 and override the will of the voters to “snatch the decision back for themselves.” Meanwhile, other officials seem to be preparing to create election uncertainty. The Georgia Election Board recently passed regulations requiring counties to hand-count ballots, a rule that could introduce major delays and irregularities, which could be exploited by partisan forces. Rep. Andy Harris, a Republican from North Carolina, suggested that because of the recent flooding, that state’s legislature should award the state’s electors to Donald Trump before the votes are fully counted.

THERE ARE ALSO CRITICAL POINTS OF SIMILARITY between the wider political culture of 1800 and that of 2024. Over the last two decades, our political parties have weakened and no longer have the same institutional power. As Sarah Longwell and I wrote in July, weak parties can’t protect moderates, encourage compromise, prevent primary challenges, cultivate bipartisanship, or weed out radical members. They are captured by the most extreme voices, which turn their most vociferous rhetoric on “soft” or “squishy” members of their own party. This climate produces, or worsens, intense partisanship.

In 1800, the extreme wing of the Federalist party—the Arch Federalists—turned on President John Adams and his allies for pursuing compromise and diplomacy with France. For the great sin of avoiding war, they referred to Adams as an “evil to be endured” and actively colluded to undermine his re-election campaign.

In 2024, former stalwarts of the Republican party, including Liz Cheney and Mitt Romney, are called “RINOs,” Republicans in name only. Republican elected officials toe the party line to prevent primary challenges from the right. Others are afraid to speak out for fear of criticism from Donald Trump and his supporters. In the days after January 6th, Rep. Peter Meijer said, “If they’re willing to come after you inside the U.S. Capitol, what will they do when you’re at home with your kids?”

In moments of intense partisan divide, verbal criticism often crosses the line to physical threats. The specter of political violence also looms over our partisan divide, just as it did in 1800. In the 1790s, most newspapers were avowedly and openly political. They regularly called for violence against their political rivals and bands of roving vigilantes happily complied, burning down offices, destroying presses, and assaulting editors.

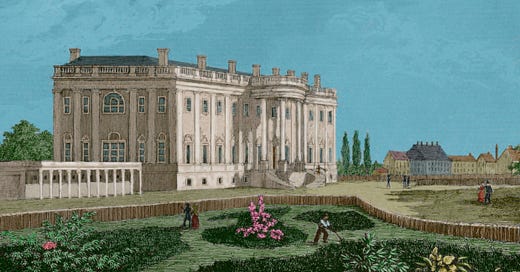

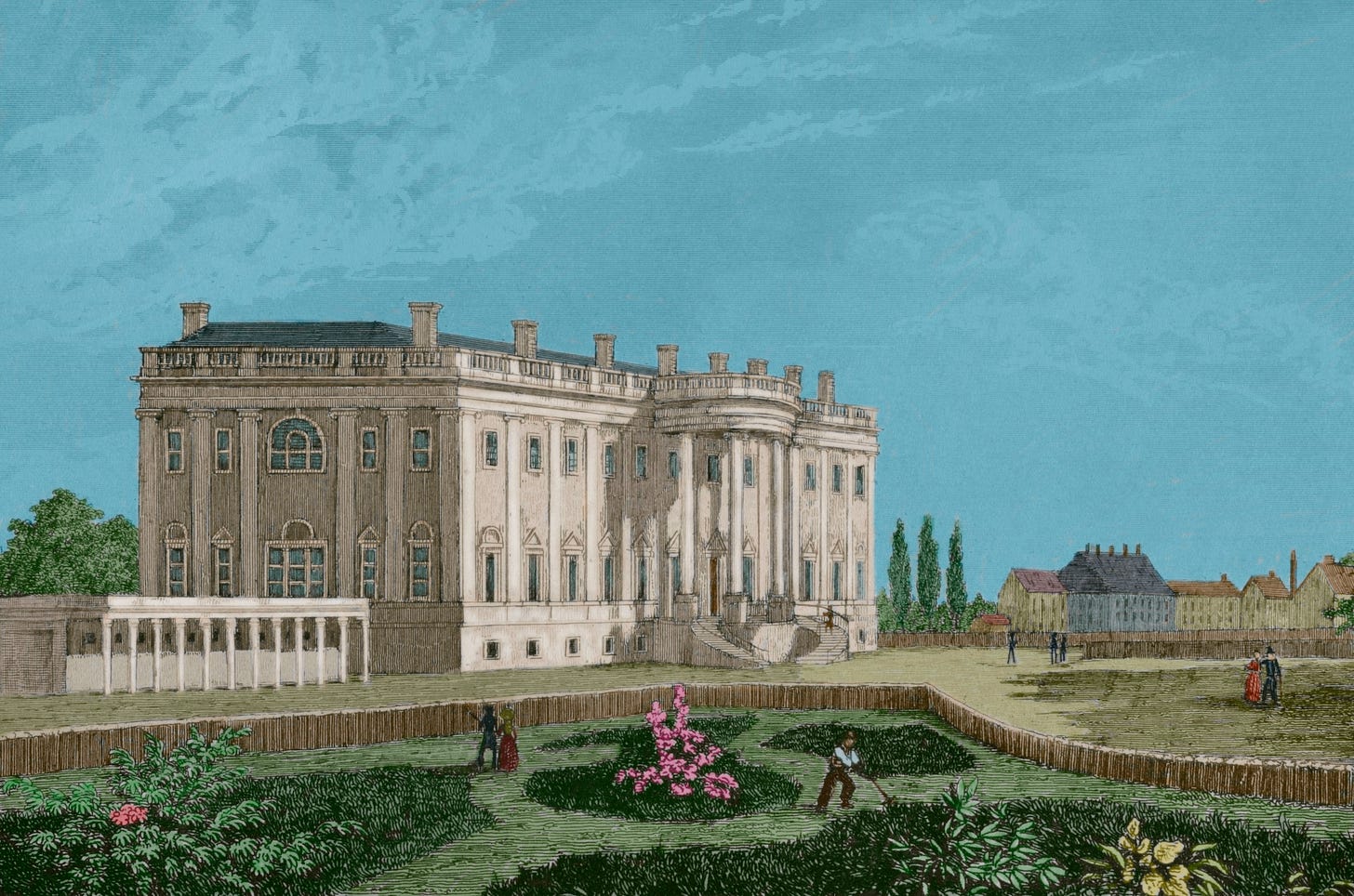

In the winter of 1800, Congress gathered for its first session in Washington, D.C. Rumors trickled into the city that the election had produced a tie between the two Democratic-Republican candidates, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. Federalists plotted to make Burr president, believing he would be more malleable. If that failed, they planned to drag out the negotiations past March 4, 1801, when they could appoint a temporary president and call a new election. (Again, echoes of the machinations of Donald Trump’s supporters in 2020 that may well be reprised in 2024.)

In response, the Democratic-Republican governors of Pennsylvania and Virginia gathered their militias on the border, ready to march into Washington City if Federalists appointed another president. Equally outraged, a mob gathered outside the Capitol and threatened to kill anyone who dared to seize the presidency from Jefferson’s hands.

Preparing for violence in 2024, polling places in swing states have installed bulletproof glass and posted snipers on the roof. The Secret Service has thwarted—though just barely—two assassination attempts on former President Trump’s life. Republican North Carolina superintendent candidate, Michele Morrow, called for the execution of Barack Obama. Trump himself has supported calls for military tribunals and suggested his political opponents should be “fired upon.”

ONE FINAL POINT OF COMPARISON between this election and the founding-era presidential elections—a small detail, and one that would seem superficial if we hadn’t recently been reminded of how much it matters: On January 6, 2025, the electoral process will officially end when Kamala Harris presides over the certification of the Electoral College vote—a quirk of our constitutional system that has seen vice presidents who sought the presidency certifying their own victories and defeats. In 1797, it was then-Vice President John Adams who opened the ballots, handed them to the clerk, and certified the tallies. He announced, “I now declare that: John Adams is elected President of the United States for four years to commence with the fourth of March next, and that Thomas Jefferson is elected Vice President of the United States.” Four years later, in 1801, it was Vice President Jefferson who opened the returns and confirmed the tie in the Electoral College.

And in 2021, Vice President Mike Pence, fulfilling the same constitutional duty, found himself under immense pressure to overturn the results and faced a mob ready to lynch him when he failed to comply.

The next year, Congress passed the Electoral Count Reform Act to clarify that the vice president’s role in the certification process is purely ceremonial and carries no legal authority to dismiss electoral returns. Nonetheless, next January 6, Vice President Harris will pick up the gavel and attempt to perform the ceremony, first peacefully demonstrated by John Adams, culminating in her announcement of her own victory or defeat. Here’s hoping the peaceful transition in 1801 is an indication of what is to come in 2024.