If we’re ranking auteurs with a great ear for pop music—those filmmakers who understand how to compile the perfect playlists to accompany their visual tricks and tics—then Edgar Wright is way up there, right behind Martin Scorsese.

Which makes sense, since it seems clear that Wright has adopted Scorsese’s sensibility when it comes to music. “A lot of music is used in movies today just to establish a time and a place and I think this is lazy,” Scorsese says in a passage on Goodfellas collected in Scorsese on Scorsese. “I wanted to take advantage of the emotional impact of the music. . . . The music was mainly chosen for the rhythm and emotion of each scene.”

You see it happen time and again in Scorsese’s body of work. The coda of “Layla” playing over the montage of bodies signals the end of an era of sorts, a melancholic look back at the time before the bad times, even though really they were all bad times. I can’t hear “House of the Rising Sun” anymore without thinking of Sharon Stone’s final moments in Casino, scared, strung out, clutching the wall of a seedy motel as she expires in a drug-induced haze. This occasionally backfires; the Van Morrison version of “Comfortably Numb” that plays over a sex scene in The Departed is just a hair on the nose. But that rare miss only stands out because everything else Scorsese does with music is so assured, so on point.

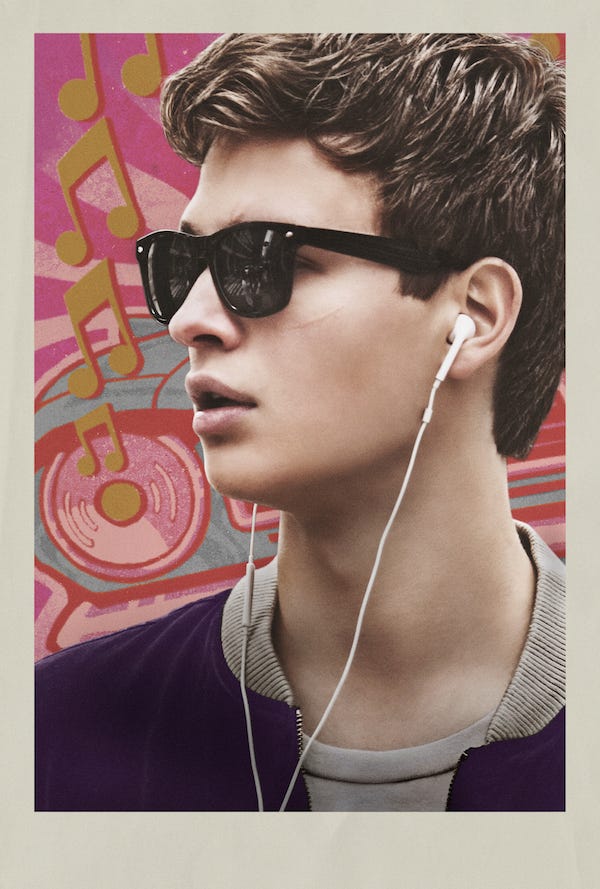

Edgar Wright has always been deft with his soundtrack choices—and music in general; the battle of the bands framing device in Scott Pilgrim vs. the World justifies the film's epic air that otherwise might have felt silly—but it feels like he took things to another level in Baby Driver. That 2017 picture featured Ansel Elgort as Baby, a getaway driver whose tinnitus has caused him to live with earbuds in 24/7, providing an insta-soundtrack to his life that in turn serves as the rhythm for his high-speed stunts. By treating most of the music as diegetic—that is, within the world of the movie—we hear how the characters interact with it, how it informs their actions and helps them move through the world.

Literally move, as in the extended single shot where Baby walks through the streets of Atlanta, singing along and dipping and dodging through crowds on the sidewalk on his way to pick up some coffee for the gang as they’re cashing out their latest score. It is a pure and joyful representation of the ways in which music can infect people, get them on a whole different rhythm; you get the sense that Baby doesn’t even realize he’s muttering the lyrics along, just out of tune. He might be embarrassed if someone pointed it out, but probably not. When you’re in the zone, you just don’t care.

And Baby Driver is often in the zone when it comes to music. I know some folks think that timing the gunfire to the beats of Focus’s “Hocus Pocus” is a mite bit hokey—a little too cutesy—but I couldn’t disagree more. It emphasizes that the modern musical, the big-budget big-dance-number type flick, has been replaced by the big action movie, plots little more than efforts to string together bravura sequences of violence. Gunfire has taken the place of tap shoes as the beat of this age’s stage, a new form of percussion.

Like Baby, Last Night in Soho’s Eloise (Thomasin McKenzie) is hopelessly captivated by music. Eloise’s record player is blasting out the sounds of the Sixties; tracks like “A World Without Love” by Peter and Gordon and “Wishin’ and Hopin’” by Dusty Springfield, both released in 1964, dot the soundscape. Indeed, from the vinyl to the posters of Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s to the retro-looking dress Eloise has constructed out of newspaper as she dances about the house to the fact that she receives her college acceptance letter on paper, I wasn’t entirely sure exactly what decade we were in as the movie began. Seeing an over-ear pair of wireless Beats on her head as she rode the train to college was, honestly, a bit jarring.

I’d like to think that dislocation was intentional on Wright’s part and not the result of my own lack of focus, an artifact of the rowdy teens* behind me at Studio Movie Grill as I tried to watch the film. I’ll assume it is, given that the elasticity of time and a curdled sense of nostalgia is a key factor in the film; the modern headphones are ever-present but they’re always belting out “granny music,” as one of her fellow students derisively puts it. As Last Night in Soho progresses, Eloise—who, early on, we see catching a glimpse of her mother’s ghost in a mirror—becomes enamored of Sandy (Anya Taylor-Joy), a spirit taking her on a tour of mid-’60s London.

Eloise finds Sandy in a dream, falling through the covers and out into the streets of Soho. Walking through the city in her pajamas, Eloise gazes up and sees a marquee for Thunderball (1965) as the cars whiz around her; she wanders into a night club only to look in the mirror and see not herself but Sandy. Dressed in a gauzy pink baby-doll dress, the point of view shifts ever so slightly and now it’s Sandy’s world we’re in; Eloise is the reflection. She follows Sandy as she makes her way through the club, bopping along to the music until she meets Jack (Matt Smith).

It’s all glamorous and delightful and, most of all, hopeful: Like Eloise, Sandy is trying to make it in the big city. She wants to be a singer. And the hinge point of the movie comes during a performance by Sandy in front of Jack and a nightclub owner: The lights go down, the spotlight is thrown on her, and Joy belts out a heartbreaking rendition of “Downtown.” For all the showiness of this movie—later on there will be flashing lights and breakdowns in perspective and an almost literal descent into Hell, one complete with faceless demons—it is this one simple set piece that stands out. Just a woman singing her heart out on stage, wowing the two-man audience.

Impressing them proves to be Sandy’s downfall, her musical talent opening up an uglier world of exploitation and degradation. I won’t say much more about the plot than that—you deserve to experience Soho’s twists for yourself—but it is striking how Edgar Wright and cowriter Krysty Wilson-Cairns have music and the joy of song contribute to Sandy’s ultimate downfall. Music again serves as torment later on, an apparition starting Eloise’s record player as things spiral out of control.

Last Night in Soho is a reminder that the old times weren’t necessarily the best of times, regardless of the art that’s survived out of them. Best to live in the present even if you want a soundtrack from the past scoring your life.

*Movie theaters are back, baby! Luckily, they quieted down as things progressed, but SMG’s servers aren’t quite as conscientious about noise levels as their peers at the Drafthouse.