Edward C. Banfield and What Conservatism Used to Mean

Hard thinking on difficult and uncomfortable questions about how to keep everything from falling apart.

IN 1937, THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT EMBARKED on what one of its chief chroniclers would later call “one of mankind’s countless recent efforts to take command of its destiny.” It wasn’t meant to be so. Casa Grande—a farm project in Arizona that was administered by the Farm Security Administration (FSA), a New Deal “alphabet agency”—was basically intended to ameliorate the extreme poverty of farmhands in the Dust Bowl and Southwest. In very small circles of conservative policy thinking, Casa Grande would become something of a fable, a cautionary tale about human beings and government intervention. But there might also be a cautionary tale about that cautionary tale—about the ways lessons can be overlearned, and the fact that ideas can have unintended consequences, too.

With characteristic humor, Edward C. Banfield began his most controversial work by remarking he must appear an “ill-tempered and mean-spirited” man. By all accounts, this wasn’t true of the renowned political scientist—but Banfield’s manner of challenging liberal dogmas imbued him with a dyspeptic aura.

It wasn’t always thus. Banfield started as a New Dealer working for the FSA. In this capacity, he visited Casa Grande twice in 1943. When the arch–New Dealer Rexford Tugwell launched a public policy program at the University of Chicago, the school that proved to be a fountainhead of so much of intellectual conservatism, he enticed Banfield to join him. Banfield’s doctoral dissertation made a deep study of Casa Grande and its failure. Although he then remained a liberal, voting for Adlai Stevenson in 1952, his belief in liberal social policy was rapidly eroding. According to his student and friend James Q. Wilson, by 1956 Banfield’s faith in planning had deserted him.

Banfield’s dissertation was published in 1951 as Government Project, a title so blandly generic and universal that it all but guaranteed the book’s obscurity. It fell out of print, but for years became something of a cult text in conservative intellectual circles, although less so in the quarter century since Banfield’s 1999 death. The release last year of a new edition, published by the American Enterprise Institute and edited by AEI political scientist Kevin R. Kosar (who is married to a granddaughter of Banfield), is an opportunity to revisit both this quietly influential work and the broader legacy of its author.

IN GOVERNMENT PROJECT, BANFIELD TELLS the story of Casa Grande from its genesis to dissolution. It was fundamentally a relief project, to give succor to the Depression poor. Administrators made the decision to establish Casa Grande as one of four FSA cooperative farms—or “collective” farms, to use a term more evocative of the Soviet Union—despite the ways this ran against the expectations of the settlers, their neighbors, the press, and Congress. (There were another eleven FSA farms that were partly, but not fully, operated cooperatively.)

The rationale for running Casa Grande on a cooperative basis arose from the understanding that a major transition was underway in American agriculture. Technology had changed the economics of farming, but culture had not kept up. Diesel tractors gave such an advantage to large-scale farmers that the small family homestead became all but obsolete. The climate and landscape of this part of Arizona further seemed to suggest the need for treating this farm differently. To make Casa Grande at all viable, it would have to be at scale, which, to maximize relief, meant it would be a cooperative. No one would own their “property as lord of the manor,” as Banfield recounted; they would “use it only in common with 59 others.”

Eventually, FSA signed off on the project, funding was appropriated, and the beginnings of a cooperative legally established. The settlers were a varied bunch. Some were Arizonans; a later batch were Okies fleeing the Dust Bowl. Casa Grande did not promise them wealth; it was relief. But for the vast majority, Casa Grande offered them housing, amenities, pay, and security superior to any they had ever experienced. It also, at least in theory, offered the sense of purpose and satisfaction that can come with work, and the sense of camaraderie that can come with being part of a team. The FSA hoped these benefits and shared experiences would hold the settlers together despite their lack of a common background and ethos.

Yet, as Banfield notes, an academic who spent a month at Casa Grande in early 1941 said that “the most striking fact about the Casa Grande project is that it seethes with dissatisfaction.” More than three quarters of the settlers were dissatisfied with the project. Why? In some respects, they were comparing their situation against an ideal. They did not like industrial-scale farming: The hours were less flexible and the roles less autonomous than on small farms. The settlers got little real training in the techniques of farming. There was little for teens or young adults to do. Their neighbors made fun of them for taking government aid. And they were still poor. But above all, the settlers simply did not like one another. Casa Grande—like most of FSA’s other collective projects—was riven with factionalism.

Despite all that, though, it was working. By 1943, as the period of drought passed and the crops and especially stock developed, Casa Grande generated profits and looked to provide real dividends. The settlers, too, were granted greater autonomy as a result of the FSA’s commitment to democratizing the farm.

A change in legislation led the FSA to try and sell the viable Casa Grande to the cooperative in 1943. Instead, almost at the first opportunity, the cooperative voted to liquidate the farm—and did so privately, rather than having the FSA do it in a cost-effective way. A large portion of the profits were eaten up by liquidators’ fees. “‘We not only killed the goose that laid the golden egg,’ Charles McCormick, who had come to Casa Grande with a family of five and assets of $200, remarked disgustedly when it was all over—‘we even threw the goddam egg away!’” The government basically broke even; almost all the settlers were worse off after the dissolution than they were at Casa Grande.

BANFIELD SOUGHT TO EXPLAIN what went wrong. For one thing, he went to great pains to assert that the FSA administrators were competent. Instead of a failure at the top, “the central fact in the history of Casa Grande,” he wrote, is that “the settlers were unable to cooperate with each other and with the government because they were engaged in a ceaseless struggle for power.” Hierarchy was not clearly established at Casa Grande, and the whole enterprise was not structured in a way that made it possible for participants to gain or compete for status in a constructive, healthy manner.

And in that sense, the leadership of FSA was to blame. The agency insisted on a form of democracy and cooperation in the functioning of the farm, rather than what might have arisen organically or some other arrangement that would have materially benefited the settlers.

Moreover, the entire project had contradictory aims. Was Casa Grande a for-profit enterprise? A relief project? An experiment in democratic governance? And was it all a bit ambitious for poorly educated sharecroppers to grapple with? (Although Banfield points out that the troublemakers among the denizens of Casa Grande were generally better educated men who felt they were slumming it.)

Finally, Banfield pointed to an overall lack of leadership. You can’t replace leaders—those individuals with an intuitive sense of competing groups’ needs and the ways to reconcile them—with bureaucrats. That’s not to denigrate bureaucrats: Banfield recognized that they are specialized, necessary, and present in every organization, public and private. But bureaucrats must work within a rational and rationalized world to succeed. They can’t lead, as Banfield defined it.

Years later, James Q. Wilson wrote,

This book, and Ed’s reflections on the cooperative farm, are, in my opinion, the central fact of his intellectual life. In the years ahead, the central question for him became an enlarged version of the Casa Grande question: how can people be induced to cooperate? And since some degree of cooperation is essential for any society, the larger question is: how can a decent society be sustained?

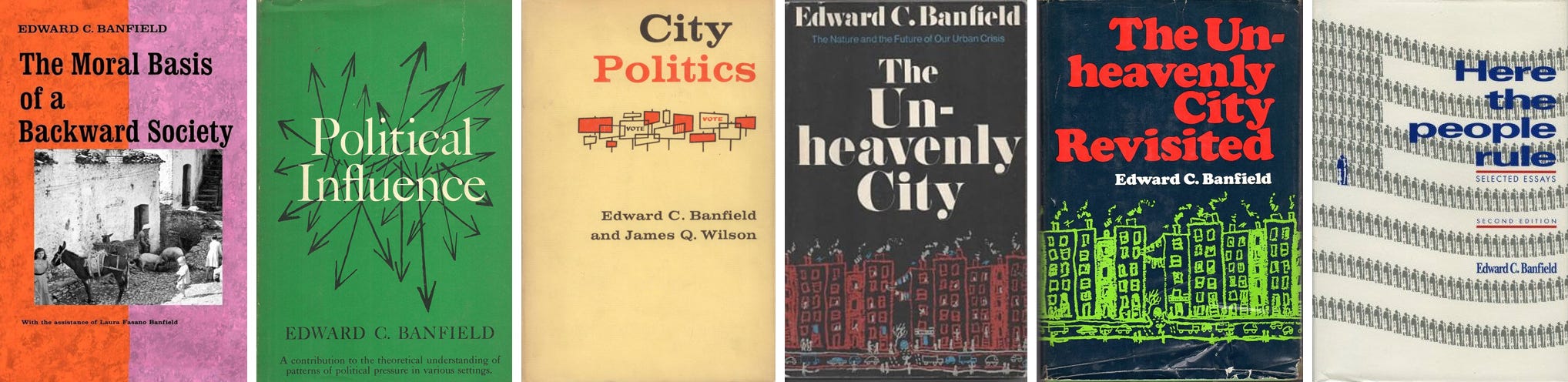

TO ANSWER THIS QUESTION, the secular Banfield visited to Mormons in Gunlock, Utah. He departed disappointed by even their limited capacity to truly cooperate, despite the community’s cultural and religious binds. After writing an unpublished manuscript on the Gunlock Mormons, Banfield went to Southern Italy with his Italian-speaking wife, Laura Fasano Banfield. The life they witnessed there informed their 1958 book The Moral Basis of a Backward Society, a work of sociology that would remain influential among both academics and policy wonks through the 1980s.

Seeking to explain the deep and persistent poverty of the Italian village of Chiaromonte, which in the book they called by the pseudonym “Montegrano,” the Banfields ruled out material or policy arguments. Their explanation for enduring poverty was a cultural one. The Montegranan villagers’ chief concern was getting the most immediate value for themselves and their immediate family, not long-term community success. Perhaps this ethos of “amoral familism” arose from Italy’s high, young mortality rates and the legal structures regarding land holding. Whatever the cause, it created a culture of short-termism that perpetuated poverty.

This linkage of culture, wealth, and time horizons—a person’s capacity to hope and plan into the future—made up key parts of the analysis in Banfield’s most famous and controversial work. The Unheavenly City (1970) challenged the core premises of the “urban crisis.” Banfield probed a range of issues—sprawl, traffic, housing problems, crime, rioting, unemployment, and schooling—and found they were in most cases a product of the tradeoffs of metropolitan living. Usually they had to do with urbanites’ real and often competing preferences.

As part of his analysis, Banfield drew heavily on categories of class to predict and explain behaviors. Banfield defined upper, middle, working, and lower classes by their relationship to time. Were they focused on the family name over generations (upper), getting themselves and their children ahead (middle), or simply living for today (lower)? “The lower-class forms of all problems are at bottom a single problem: the existence of an outlook and style of life which is radically present-oriented and which therefore attaches no value to work, sacrifice, self-improvement, or service to family, friends, or community.” The persistence of this class, even if small, “will nevertheless be large enough to constitute a serious problem—or, rather, a set of serious problems—in the city.”

At pains to emphasize that “lower class” was not code for “black,” Banfield nevertheless galloped through the minefield of race. He argued that the race riots were mostly not about race, but lower-class pursuit of fun and profit. He suggested segregation was at least partially voluntary. And he argued present discrimination was not a major driver of inequality (while leaving plenty of scope for historic injustice’s enduring impact). “Widespread as it still is—racial prejudice today is of a different order of magnitude than it was prior to the Second War,” Banfield argued in the revised version of The Unheavenly City. He persistently found that white prejudice was no longer the chief explanation for many of the inequalities in the black experience. (He made a similar point in the New York Times in October 1970: “Misplaced emphasis upon ‘white racism’ is likely to make matters worse both by directing the attention of policy makers away from matters that should be grappled with and by causing Negroes to see even more prejudice than actually exists.”) At the same time, Banfield’s class analysis could be read as giving credence to racial stereotypes. “Concretely,” he indicated, “racial and class prejudice are usually inextricably mixed, and so are prejudice and justifiable antipathy.” He knew how all this would be received; it was at the start of The Unheavenly City that he wrote that he likely comes across as “an ill-tempered and mean-spirited fellow.”

Before this book, Banfield had been highly regarded but little known. Harvard had poached him from Chicago for its political science department. Daniel Patrick Moynihan touted him to the Nixon White House just before the book’s publication as “a solid Republican, with impeccably liberal views on race, and an immense knowledge of why it is so hard to get anything done.”

The New York Times’s reviewer, Jeff Greenfield, panned The Unheavenly City, arguing that Banfield’s “largely theoretical” analysis “totally absolves institutions now in power.” This mattered because Banfield had “an important voice these days in the Nixon Administration’s planning of its urban policies,” including as chairman of a task force on the Model Cities Program. “We may assume that this book is a part of the thinking now going on within the Nixon Administration,” Greenfield warned. (Ironically, the quotation Greenfield uses to conclude his review—“God save us from a government of experts,” attributed to Woodrow Wilson—expresses a sentiment Banfield would have endorsed.)

Notwithstanding the negative review, the Times two weeks later gave Banfield the unusual privilege of space two days in a row to showcase his arguments about class.

Over the next couple of years, The Unheavenly City provoked a dramatic reaction, amounting to a slow-motion version of what we would now call an attempted cancellation of Banfield. By 1972, members of the New Left organization Students for a Democratic Society were quoted in the Times linking Banfield to highbrow racism. And by March 13, 1974, the anti-Banfield sentiment among left-leaning students reached the point of direct action: Around 100 students led by SDS physically prevented Banfield—surrounded by five campus police—from reaching the speaker’s platform at the University of Toronto. The students called Banfield an “academic racist” who slurred blacks and Italians. Banfield left, saying, “I don’t feel called on to explain my views.” A week later, another SDS chapter disrupted a Banfield lecture at the University of Chicago by storming the stage and chanting for 90 minutes.

The following month, John Berg and Stephen Jay Gould linked Moynihan and Banfield to academic racism, grossly oversimplifying Banfield’s thought to claim that he argued “black children are unable to learn because of their allegedly inferior culture”—a classic example, Berg and Gould write, of “blaming the victim.”

Banfield left Harvard in 1971 to take a newly endowed chair at the University of Pennsylvania. He claimed Penn simply offered him a better position. After teaching at Penn for three academic years, Banfield returned to Harvard, where he stayed until his death in 1999 at the age of 82.

KOSAR, THE EDITOR OF THE NEW EDITION of Government Project, calls Banfield “the earliest neoconservative,” and Government Project “the first neoconservative book.” How appropriate are those labels?

Before neoconservatism became bound up with post-9/11 American foreign policy—the war in Iraq and George W. Bush’s “Freedom Agenda”—it was known for its involvement in domestic policy. Its first generation coalesced as critics of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. Often sociologists or political scientists, the neoconservatives of the 1960s and early ’70s brought a detached, often empirical, and skeptical approach to policy analysis. They were often liberals or even leftists who had shifted to the right in response to recent cultural and political shocks.

Peter Steinfels, a critic and chronicler of neoconservatives, has described Banfield as “an ‘ultra’ among the neo’s” for the intensity of his criticism. To Steinfels, Banfield’s “assurance about possessing the facts, or possessing a sophisticated sense of historical complexity” demonstrated what “makes the neoconservatives so persuasive.” Others, from both the left and right, have considered Banfield a more traditional conservative “who sometimes fellow-travels with neoconservatives.”

Certainly, Banfield turned right earlier—and harder—than many of the other neoconservatives. He was already a Republican in the early 1960s, for instance, and reviewing books by John Kenneth Galbraith and Milton Friedman for William F. Buckley’s conservative magazine National Review. Buckley and his confreres even considered Banfield a candidate for a Scholars for Goldwater group in 1964. These were steps far beyond the likes of neoconservative godfather Irving Kristol at that point.

Yet for all the mismatch in timing, Banfield sociologically and intellectually really was a neoconservative avant la lettre. His association with the neoconservatives ran much deeper than did his association with traditional conservatism. His student and close colleague James Q. Wilson was a key neoconservative thinker. As was Kristol, whom Banfield invited into association with the Nixon administration before anyone else, in 1968. Banfield wrote substantive articles for Kristol’s neoconservative journal The Public Interest, where other authors frequently and approvingly cited his work. And like most of this first generation of neoconservatives, he was first a professor ensconced in an elite university—which is to say, he was not a full-time conservative intellectual.

Analytically, as Steinfels suggested, Banfield is a potent example of the neoconservative mindset. In 1985, upon the twentieth anniversary of The Public Interest, Irving Kristol wrote, “It is not too much to say that it was a spirit of skepticism—not pessimism, it must be emphasized, just a healthy skepticism—that gave birth to The Public Interest.” Banfield possessed this skepticism. He challenged liberal shibboleths to the point of controversy; he questioned rationalism and planning; he was skeptical about humanity’s capacity to get ahead of itself.

In a critical 1974 assessment of neoconservative thinking on crime, sociologist Edwin M. Schur described Banfield’s views as “typical” of neoconservatism. “Skeptical of the liberal’s ability to produce social progress,” neoconservatives like Banfield, he wrote, have “abandoned the effort to head off crime through basic socioeconomic and legal change.” Believing true poverty to “have already been substantially ameliorated,” they tended to explain crime by reference to the criminal. Crime—and most social ills—are basically eternal, and to be managed rather than solved as “a reflection of social malaise.”

This assessment is perhaps too harsh. Banfield did not abandon altogether the possibility of policy interventions, although it’s true he thought policymakers’ room to maneuver was severely constrained. Likewise, Kristol remarked in his 1985 retrospective that “the failure (or at least non-success) of so much of social policy in the past twenty years can be exaggerated. Not every program failed and there are a few important ones that represent positive achievements.” Indeed, “The Public Interest has always emphasized the modestly positive along with the skeptical.” Yet on the right writ large there has been a clear decline from skepticism toward nihilism—toward a belief that policy interventions fail so often and character is so intractable that it is almost never worth it to attempt to solve social problems through policy.

THE DIRE STATE OF RIGHT-WING POLITICS in America today is hardly the fault of Banfield and the early neoconservatives. But if so inclined, one could draw a line from their acidulous criticism of liberal policies through to Ronald Reagan’s gibe about the “nine most terrifying words in the English language” and on to today’s aversion to the administrative state and demonization of the Deep State. To be sure, opposition to the federal government and liberal policy has always been foundational to the American right. But Banfield and the neoconservative academics provided the heavy artillery that demolished the policy platforms of midcentury liberalism, while helping grant legitimacy to the wider conservative movement.

Banfield, Wilson, Kristol, Moynihan, and the other early neoconservatives placed stock in leadership and saw the rough-and-tumble of democratic politics—even machine politics—as a positive force for reconciling the interests of competing groups and meeting people’s needs. But having delegitimized the capability of government, the neoconservatives contributed to a void in public policy—a wide-open space in which arose a theoretically apolitical neoliberal approach to policy that bypassed traditional politics.

“Ed had no simplistic faith in markets,” Wilson wrote about his former teacher. When reviewing Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom for National Review, Banfield rejected Friedman’s absolute prioritization of freedom. Because “however much one values freedom, one must value other things even more.” These include “the maintenance of a consensual order which permits reasonable discussion, the exercise of reason itself, and whatever substantive values the exercise of reason recommends in the particular circumstances.”

It was not the intention of Banfield and the neoconservatives, but by undermining government and facilitating the rise of market-oriented criteria decision-making, they transformed the political arena. Once-legitimate spaces for groups’ competing needs to be reconciled vanished. Instead of political struggle for material benefits, conflicts became—like at Casa Grande—irrational fights over status. The modern rival to a traditional democratic leader is less the bureaucrat than the consultant.

On the one hand, we might regret the neoconservative lessons that have been overlearned—including by themselves. As Joseph Epstein once wrote, before his neoconservative fellow-traveling days, “It is one thing to say that on certain brutally tough social problems we don’t as yet have any convincing solutions; quite another to say, as those who talk about the limits of social policy imply, that none exist or are likely to be found.”

On the other hand, we can also regret the disappearance of early neoconservatism as a distinct outlook on the right. The early neoconservatives had a skeptical but nonetheless real—even in Banfield’s case—belief in the salutary role of the state. Their realism extended not just to skepticism about policy, but attention to real problems—not the largely symbolic fixations of the Trumpist right.

“Ours has always really been a meliorist frame of mind,” wrote Kristol of the neoconservatives around The Public Interest. “The world is not coming to an end, and American society is not going to collapse, merely because so many liberal social programs have not worked as intended. What is needed are better social programs—though the best are not always identified as being a social program of any kind.”

As it stands, Banfield’s fundamental question (as Wilson phrased it)—“How can a decent society be sustained?”—remains as haunting as ever.