When a Shitposter Runs a Social Media Platform

Bad news for democracy: Elon Musk loves to promote fringe figures and to denigrate responsible journalists.

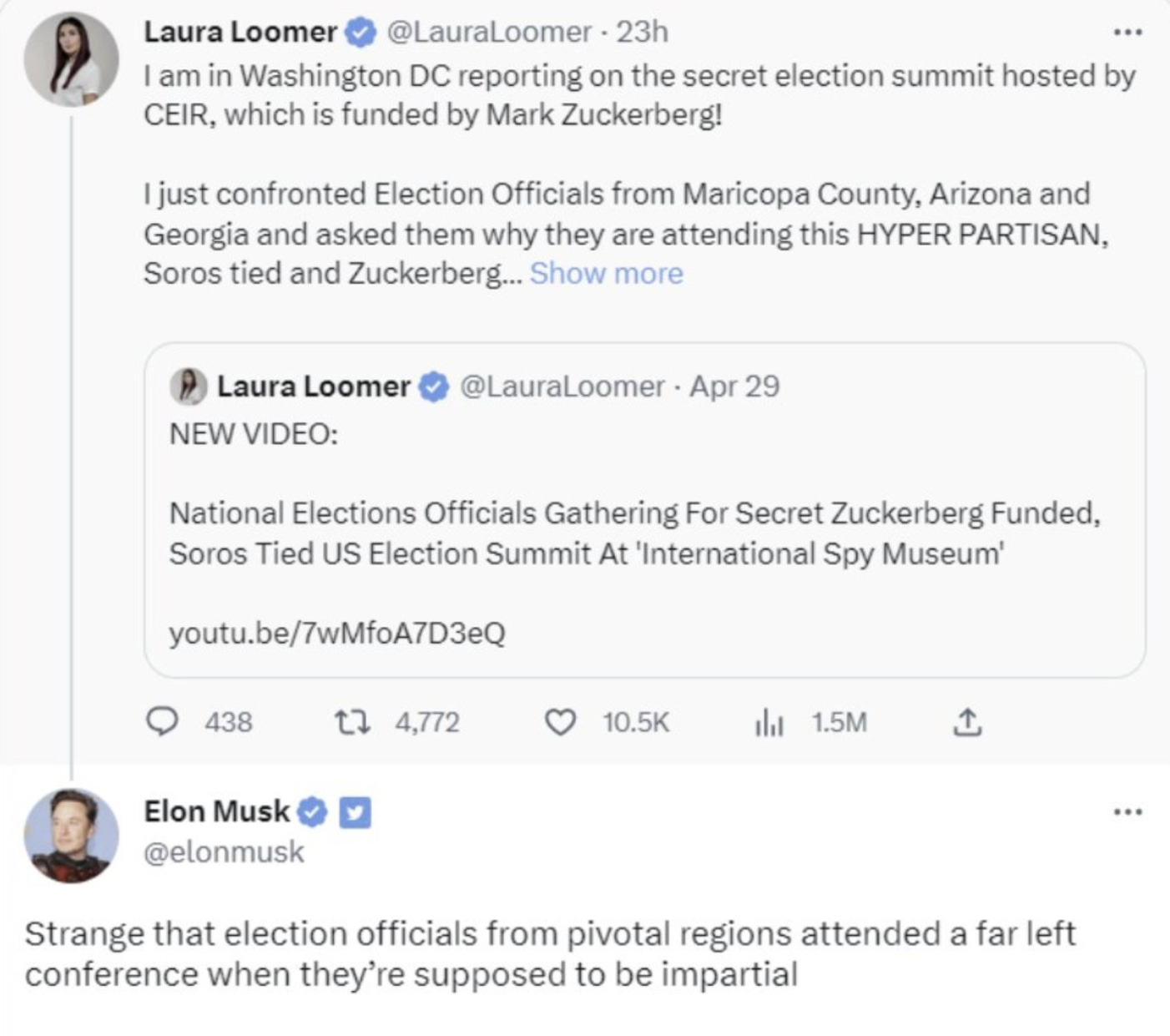

In recent years, we have become used to a certain level of political disinformation on social media, more or less accepting it as the cost of protecting free speech even as we continue to debate how much moderation should take place. Now, however, Elon Musk’s ownership of Twitter is forcing us to come to terms with a new reality: a social media platform where the person running it is himself spreading the misinformation. Where to begin? Last week, Musk responded to a tweet by Laura Loomer, one of many unhinged conspiracists who have been welcomed back to the platform since he took over:

Note that Musk is responding in earnest, and in a way that legitimizes the tweet’s assumptions and claims. The person he is responding to had previously been banned for life for violating Twitter’s hateful conduct policy. Loomer is a self-described white nationalist and Islamophobe, and her ostentatiously hateful views made it difficult for her to have an online life at all, for a time: She was previously banned from Facebook, Venmo, PayPal, GoFundMe, and Instagram. She was banned from CPAC. She was even banned from Uber and Lyft. How the hell do you get banned from Uber and Lyft? She blamed a wide-ranging conspiracy trying to silence her; in reality, she was suspended for a hate-filled Twitter rant about “never want[ing] to support another Islamic immigrant driver” through the rideshare services. This kind of thing is Loomer’s stock-in-trade. Here she is in 2017 celebrating the deaths of migrants trying to reach Europe:

In addition to being an endless fountain of prejudice and hate, Loomer is conspiracy theorist. For example, she claimed that the 2017 mass shooting in Las Vegas was a false flag operation, or organized by Antifa, or ISIS, and involved an FBI coverup. Her conspiracy theorizing extends to her political activities: Despite squarely losing a Republican primary in Florida in 2020, she claimed she won it but had her victory stolen through fraud. At the afterparty that followed her non-concession speech, she hosted fellow-traveling white nationalists and Nazis, like Nick Fuentes and Peter Brimelow:

Apparently professional racists Peter Brimelow and Nick Fuentes were at the election night party with Laura Loomer in Florida. They were joined by an assortment of other racists and far-right figures. pic.twitter.com/QTbOT9T7b9

— Nick Martin (@nickmartin) August 24, 2022

Need it even be added that Loomer believes the 2020 election was stolen from Donald Trump, too? Laura Loomer is perhaps the single least reliable source of political information in America. Her errors are not random but predictably associated with a hate-filled worldview. Yet Laura Loomer is also a person Elon Musk regards as a credible source of information on election administration, one he is happy to share with his 140 million followers. Elon Musk welcomed her back to Twitter as part of a larger reorienting of the platform to, as he put it, prioritize free speech over content moderation; numerous other election deniers came back at the same time. But he didn’t just let them back into the room so they could hang out in their own dark corner; he pulled them into the very center of the action by regularly interacting with them, often assuring them that he would “look into” their claims of censorship, shadowbanning, or other misdeeds on the part of the platform under earlier ownership. And he hangs out online not just with people who believe the election was stolen, but with people like Tom Fitton and Jenna Ellis, who actually tried to help overthrow the 2020 election, and Mike Cernovich, an original Pizzagater.

This is an unfortunate and pernicious pattern. Musk often refers to himself as moderate or independent, but he routinely treats far-right fringe figures as people worth taking seriously—and, more troublingly, as reliable sources of information. By doing so, he boosts their messages: A message retweeted by or receiving a reply from Musk will potentially be seen by millions of people. Also, people who pay for Musk’s Twitter Blue badges get a lift in the algorithm when they tweet or reply; because of the way Twitter Blue became a culture war front, its subscribers tend to skew to the right. Sometimes they skew quite far to the right. If you read the replies to almost any high-profile journalist’s tweets these days, you will likely see a banquet of conspiracist reaction taking place among blue-check reply guys—a dynamic that inspired the #BlockTheBlue campaign soon after the new system was implemented. The important thing to remember amid all this, and the thing that has changed the game when it comes to the free speech/content moderation conversation, is that Elon Musk himself loves conspiracy theories. A lot of his centrist posturing is simply cover for attacks on various perceived consensus positions: It isn’t just that progressive activists have gone too far with pronouns or whatever, but that a “woke mind virus” is corrupting our youth. The media isn’t just unduly critical—a perennial sore spot for Musk—but “all news is to some degree propaganda,” meaning he won’t label actual state-affiliated propaganda outlets on his platform to distinguish their stories from those of the New York Times. In his mind, they’re engaged in the same activity, so he strikes the faux-populist note that the people can decide for themselves what is true, regardless of objectively very different track records from different sources. This is not new shtick for Musk. The first warning sign went up years ago when he labeled someone a “pedo guy” for criticizing one of his more outlandish ideas. Musk’s “just asking questions” maneuver is a classic Trump tactic that enables him to advertise conspiracy theories while maintaining a sort of deniability. At what point should we infer that he’s taking the concerns of someone like Loomer seriously not despite but because of her unhinged beliefs? It is not as if Musk is incapable of skepticism. For example, he repeatedly cast doubt on what ultimately turned out to be accurate reports that the gunman responsible for a Dallas-area mass shooting this month had neo-Nazi sympathies. But Musk’s skepticism seems largely to extend to criticism of the far-right, while his credulity for right-wing sources is boundless. All of this was already concerning when Musk was simply the world’s wealthiest man and worst shitposter, but it should frankly alarm us now that he oversees the decisions of the major social media platform where he posts.

Brandolini’s Law holds that the amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it. Refuting bullshit requires some technological literacy, perhaps some policy knowledge, but most of all it requires time and a willingness to challenge your own prior beliefs, two things that are in precious short supply online. This is part of the argument for content moderation that limits the dispersal of bullshit: People simply don’t have the time, energy, or inclination to seek out the boring truth when stimulated by some online outrage. Letting the BS flow unimpeded entails accepting that it is going to get all over a lot of people. Musk’s heralding of the expansion of Twitter’s “community notes” feature, which allows for crowdsourced factchecking, ignores how little it appears to have done to stop the flow of misinformation. Here we can return to the example of Loomer’s tweet. People did fact-check her, but it hardly matters: Following Musk’s reply, she ended up receiving over 5 million views, an exponentially larger online readership than is normal for her. In the attention economy, this counts as a major win. “Thank you so much for posting about this, @elonmusk!” she gushed in response to his reply. “I truly appreciate it.” Let’s examine the content of her tweet. Contrary to Musk’s characterization, the Summit on American Democracy, which is a meeting of the Center for Election Integrity & Research (CEIR), is not a “far left conference.” It is a gathering of normie election officials figuring out how to manage the logistics of elections. Don’t believe me? The agenda and roster of speakers for the event are available online. The proceedings were recorded, and you can watch every presentation. There is nothing secret about any of it. It features officials from blue states and red states, Republicans and Democrats. (Note: Bulwark publisher Sarah Longwell was among the speakers.) The conference addresses topics that both parties say they care about, like maintaining the integrity of election rolls and counting ballots more quickly. It is true that the event does not cater to all viewpoints. You will not hear CEIR presenters discussing whether Donald Trump really won the 2020 election but was denied thanks to a plot cooked up in Venezuela. It does not feature speakers who will explain how to make voting more difficult, or block student voting, as someone at a GOP donor event might do. CEIR basically reflects what used to be the normal bipartisan approach to voting: that we should help people to vote while maintaining the integrity of the process. The conference does include one topic that is relatively new, which is the harassment of election officials. Election deniers fared poorly in the 2022 midterms, but that does not mean that hardworking and hard-pressed election officials will stick around for next year’s polls. After the 2020 election, about one third of election officials reported feeling unsafe, with about one in six reporting that they had been threatened because of their job. Last spring, about one in five local election officials said they planned to quit before the 2024 election. America relies on a highly decentralized election system, which has its strengths and weaknesses. A plus is that it is virtually impossible for bad actors to perpetrate massive, coordinated election fraud in this country because of the huge numbers of conspirators across the country who would have to be involved for it to work. A minus is that there is a lot of variation in administrative capacity, and we must rely a lot on the goodwill of election officials to stay in their often poorly compensated jobs. Conspiracy theorists like Loomer have done much to drain that goodwill, and Elon Musk appears happy to help her continue her work of depleting it further.

But the problem isn’t limited to elevating Loomer. Musk had his own stock of misinformation to add to the pile. After interacting with her account, Musk followed up last Tuesday by tweeting out last week a 2021 Federalist article claiming that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg had “bought” the 2020 election, an allegation previously raised by Trump and others, and which Musk had also brought up during his recent interview with Tucker Carlson.

But the “interesting” Federalist article Musk tweeted makes misleading claims and leaves out key context, insinuating that Zuckerberg’s money had been decisive in swinging the election for Biden. An accurate account of Zuckerberg’s donation and what was done with the money would run roughly this way: During 2020, with the pandemic in full swing, it was clearly going to be difficult for people to vote in person as they had in previous elections. Some states and localities recognized this by providing extra resources to election administrators and more flexible arrangements for collecting ballots, like dropboxes. Some states did not change their plans for conducting the vote, which raised concerns that the pandemic-era election would see reduced turnout in urban areas, where more people would have to be crammed into fewer voting spaces, risking the further spread of COVID. Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan donated hundreds of millions of dollars to address this problem. The money went to two nonprofits that then distributed it. Zuckerberg and Chan made no decisions on how the money was used by the organizations after they made the donations. Election administrators could apply for grants to help plug budget holes and improve outreach. Some 2,500 election offices in 49 of the 50 states applied for and received money from the Center for Tech and Civic Life, which spent about $350 million. And CEIR spent $64 million in 22 states on grants related to voter education. In some cases, the nonprofits disbursed the funding despite legal challenges mounted by Republicans. One criticism that has been directed toward this project is that more money flowed to bluer districts. But this largely reflects the correlation between voter density, stretched resources, and blue-district voting patterns: Many of them cover urban areas where the requirements and per-capita costs of running an election are simply greater. And as Philip Bump pointed out in the Washington Post, that extra spending did not shift the basic reality that in 2020, as with previous elections, there remained a significant gap between turnout in whiter (and more rural) settings and less white districts; whiter districts tend to vote at higher rates. It is also the case that grants required some matching funds. If that, in turn, required state legislative approval, applications were less likely to come from red states. Some election officials in red states apparently even turned down grants because of political pressure. Here is what the chair of the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, Benjamin Hovland, said while testifying to Congress about the grants:

I have talked to the people who distributed that at the Center for Tech and Civic Life and election officials who received it, and that was going for the basics. You know, that was going for PPE. That was going to disinfect and clean and to procure significantly, or enough polling locations, places that had closed down because maybe they were senior centers and weren’t available, also locations that had enough room to social distance, both for voters and staff.

Those “Zuckbucks” sure sound a lot less ominous when the purchases are explained this way! The actual scandal here is not some hidden conspiracy, but the partisan division on whether governments should encourage people to vote. Republicans believe that higher turnout, especially in urban areas, is bad for them. In states they control, they have used false claims of crooked elections to impose new burdens on voting. Not surprisingly, several Republican-controlled states passed laws barring outside funding for election offices the year after Zuckerberg’s donation. If Zuckerberg wanted to use his vast fortune to tip the election, it would have been vastly more efficient to create a super PAC with targeted get-out-the-vote operations and advertising. Notwithstanding legitimate criticisms one can make about Facebook’s effect on democracy, and whatever Zuckerberg’s motivations, you have to squint hard to see this as something other than a positive act addressing a real problem. More to the point, if Zuckerberg had wanted to tilt the election, he didn’t need to spend any money at all; he could have simply used his own platform to do it. Indeed, there were credible accusations that Facebook did not do enough to counter misinformation about election fraud. An analysis by the Washington Post and ProPublica found that Facebook allowed “650,000 posts attacking the legitimacy of Joe Biden’s victory between Election Day and the Jan. 6 siege of the U.S. Capitol, with many calling for executions or other political violence.” It’s worth mentioning that the refutations I’ve just sketched of the conspiratorial claims made by Loomer and Musk come out to around 1,200 words. The tweets they wrote, read by millions, consisted of fewer than a hundred words in total. That’s Brandolini’s Law in action—an illustration of why Musk’s cynical free-speech-over-all approach amounts to a policy in favor of disinformation and against democracy.

Moderation is a subject where Zuckerberg’s actions provide a valuable point of contrast with Musk. Through Facebook’s independent oversight board, which has the power to overturn the company’s own moderation decisions, Zuckerberg has at least made an effort to have credible outside actors inform how Facebook deals with moderation issues. Meanwhile, we are still waiting on the content moderation council that Elon Musk promised last October:

It’s unclear whether this was simply another bluff on Musk’s part, or if he’s left the idea to gather dust while dealing with other priorities. But in any case, rather than allowing credible individuals outside his organizations to rein him in, Musk is running Twitter based on his gut alone—advertisers, traffic-driving power users, and media organizations be damned. And it turns out that the instincts of an incessant shitposter with a penchant for conspiracy theories and a fondness for right-wing cranks may not be the best thing for American democracy, or democracy around the world. The problem is about to get bigger than unhinged conspiracy theorists occasionally receiving a profile-elevating reply from Musk. Twitter is the venue that Tucker Carlson, whom advertisers fled and Fox News fired after it agreed to pay $787 million to settle a lawsuit over its election lies, has chosen to make his comeback. Carlson and Musk are natural allies: They share an obsessive anti-wokeness, a conspiratorial mindset, and an unaccountable sense of grievance peculiar to rich, famous, and powerful men who have taken it upon themselves to rail against the “elites,” however idiosyncratically construed. And if the rumors are true that Trump is planning to return to Twitter after an exclusivity agreement with Truth Social expires in June, Musk’s social platform might be on the verge of becoming a gigantic rec room for the populist right. These days, Twitter increasingly feels like a neighborhood where the amiable guy-next-door is gone and you suspect his replacement has a meth lab in the basement. A report in Vox suggests that, Musk’s claims of record usage notwithstanding, Twitter is continuing a longstanding traffic decline. But even as its star fades, because of its important role in the world of online journalism over the past decade, Twitter could still exercise an influence in upcoming elections—especially if Trump, who drove countless news cycles with his offhand tweets, does return to it. But even if Twitter’s increasingly broken information environment doesn’t sway the results, it is profoundly damaging to our democracy that so many people have lost faith in our electoral system. The sort of claims that Musk is toying with in his feed these days do not help. It is one thing for the owner of a major source of information to be indifferent to the content that gets posted to that platform. It is vastly worse for an owner to actively fan the flames of disinformation and doubt.