Baz Luhrmann’s new Elvis Presley movie is gloriously goofy: a musical biopic as filtered through the lens of a superhero epic, an amusing combination that results in pure, uncut American mythologizing.

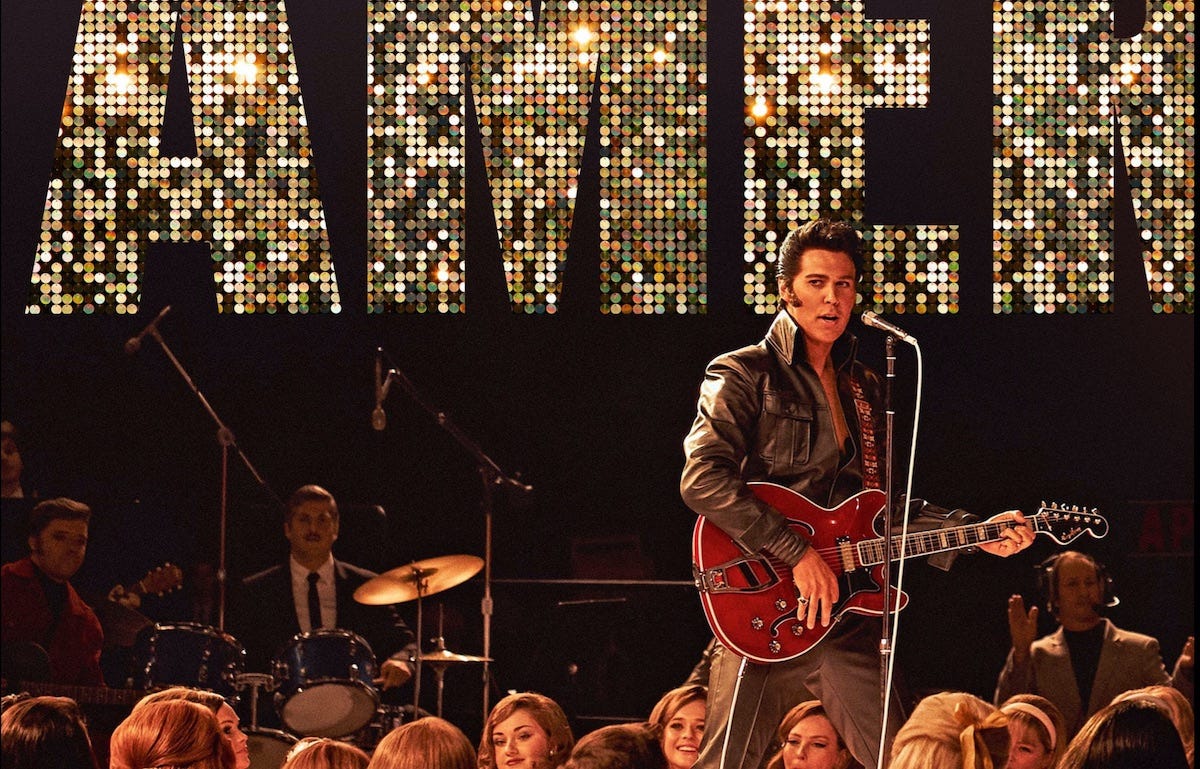

Elvis posits Elvis (Austin Butler) as an American god and is not subtle in this supposition: Early on, we see the young Presley running about town with a giant Shazam/Captain Marvel lightning bolt hanging from his neck. (One imagines it is on loan from elsewhere in the Warner Bros. empire, given that the insignia is a key part of Black Adam and Shazam! Fury of the Gods, both on the horizon.) The entire look of the film calls to mind certain comic book adaptations, flicks like Sin City or 300; the backgrounds are frequently filled in by an all-encompassing green screen leading to an aggressive artificiality that heightens everything almost beyond reality.

Colonel Tom Parker (Tom Hanks, in a fat suit and with a ridiculous accent) says that Presley’s superpower is music. That’s half right. His real superpower is the little wiggle in his hips produced while singing music, the one that drives women in the audience at staid country hoedowns to involuntarily stand up and scream and toss their undies onstage. His music—his melding of white country and black rhythm and blues—had its own power, of course, but it’s the live performance that drove people wild and gave him his ability to control the minds of women.

Again: this is not a subtle movie. At one point, while listening to a record of Presley’s performance, Parker dismisses the suggestion that Elvis be allowed to play with his carnival. They couldn’t put a colored fella in their show, after all. But when informed of Elvis’s skin color he stops, pauses, and repeats the new knowledge: “He’s … he’s white? He’s white!”

This is how director Luhrmann—who also earned three writing credits in one of the more convoluted credits lists I’ve ever seen—handles the question of cultural appropriation and the very problematic nature of Elvis Presley achieving immense success even as African-American artists languished. Which is to say, he handles it with the same amount of delicacy and grace as a sociology undergrad would handle it. And if you weren’t yet quite sure what to think, Elvis uses his superpower at one point to drown out a Klan rally meeting a couple miles down the road, the speaker at which is denouncing Presley for his dangerous habit of race mixing.

However, that very bluntness is key to making the myth work, this idea of Elvis as a great American superhero, a crusader for the downtrodden, an artist desperate to infuse his pop with politics, a man dedicated to modern ideals of equality and faced with an equally modern foe: the dread villain, cancel culture. Indeed, Elvis literally says at one point that he has been told by Parker that he must stop his wiggling and become a proper hero for proper people: “Either that, or I get canceled.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is no stop on this whirlwind tour of his visit to Nixon’s White House—that would muddle the myth a bit too much.

Some friends have suggested this movie hews to the structural patterns of the musical biopic laid out by the too-accurate-for-comfort parody Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story. If you’re a fan of such films, you should watch Walk Hard, but only if you never want to see a by-the-numbers biopic again. And while there are, of course, elements of that picture here—success, struggles, drugs, rebirth, death—Elvis is actually more reminiscent of Amadeus.

Presley’s story is told through the eyes of Parker, whom we meet in the midst of a hallucinatory deathbed episode. Parker, importantly, considers himself the equal of the King: he’s the Snowman to Elvis’s Showman, delivering “snowjobs” to unwitting suckers to lighten their pockets of hard-earned cash. And while Parker’s razzle dazzle was undoubtedly helpful in getting Elvis’s career off the ground, Elvis had raw, magnetic charisma that rendered Parker’s brand of snowmanship unnecessary.

I’ve seen some annoyed mutterings that putting Parker at the center of so much of the film is needless at best and a distraction at worst, but this feels wrong. We need to see Presley’s greatness reflected in Parker’s mediocrity, to see a fake to appreciate the real thing. The King cannot rise to mythic status without seeing what it is, precisely, that he’s rising above. The striving pettiness of mere mortals. The ugly squabbling and penny pinching. The monetization of hate and love alike.

Hanks in his fatsuit is a grotesque, all the better to compare to Butler’s slender (at first) Presley. Butler sells the larger-than-life ideal of Presley—the superheroic Elvis, if you will; the iconic Elvis—in a way that helped me, someone who has never been that into Elvis or his music, appreciate him more. Both Hanks and Butler will garner Oscar buzz and both will deserve it; they are a forceful tandem and they’d better be, given that one or both is in most every scene.

Luhrmann, the director of Moulin Rouge! and The Great Gatsby, is an acquired taste that I never quite acquired; he’s the cinematic equivalent of doing molly on a rollercoaster through a rhinestone factory. But there’s a higher purpose to his manic extravagances in Elvis, all the quick cutting and dolly moves and cartoonish backgrounds serving to turn the King into an American God.

Besides: The King was never a stranger to gaudy excess, now was he?